Budget

Budget

Are Arizona Public Employees Over Compensated?

April 2, 2012Are Arizona Public Employees Over Compensated?

Jeffrey H. Keefe, Ph.D.

Fellow, Grand Canyon Institute

Dave Wells, Ph.D.

Fellow, Grand Canyon Institute

Executive Summary

The research in this paper investigates whether Arizona public employees are overpaid at the expense of Arizona taxpayers. The Arizona legislature is considering four bills including one that would ban state and local governmental entities from recognizing public sector unions, prohibit collective bargaining, and meeting and conferring with union representatives. According to the bill’s proponents, taxpayers are unfairly burdened by public workers’ contracts negotiated by unions. Senator Rick Murphy, R-Peoria, who introduced Senate Bill 1485 prohibiting meetings with union representatives, declares that it is inappropriate when employees “take on the mantle of a public servant, then group up together and use leverage on the people they claim to serve.” He adds, “There needs to be a better balance” His statement suggests that state and local public employees in Arizona are excessively compensated.

Likewise, G overnor Jan Brewer’s proposal to shift significant numbers of state employees to at will status, while couched in the context of more flexible pay, will reduce the attractiveness of state employment. If the state doesn’t meet market rates, the state will be increasingly challenged in hiring and retaining the best employees.

overnor Jan Brewer’s proposal to shift significant numbers of state employees to at will status, while couched in the context of more flexible pay, will reduce the attractiveness of state employment. If the state doesn’t meet market rates, the state will be increasingly challenged in hiring and retaining the best employees.

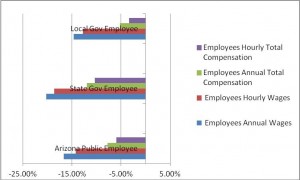

The data analysis presented in Figure 1 indicates that Arizona public employees, both state and local government employees, are not overpaid. Comparisons controlling for education, experience, hours of work, organizational size, gender, race, ethnicity, citizenship, and disability reveal that public employees in both state and local governments earn less than comparable private sector employees. On an annual basis, full-time Arizona state and local employees are under-compensated by 7.8 percent in comparison to otherwise similar private sector workers. When comparisons are made for difference in annual hours worked, full-time Arizona state and local employees are under-compensated by a smaller 6.0 percent.

These results sharply contrast with the analysis presented by the Goldwater Institute in their January 24 2012 policy report, which suggests that public unions caused Arizona state and local government worker compensation to be $560 million above market rate. Their analysis is inaccurate due to poor methodology.

Unlike the Goldwater analysis, our data set includes a random sample of 10,000 demographically detailed Arizona workers in both the public and private sector. The Goldwater Institute relied on statewide averages, so Arizona was but one point among all the states. In addition, Goldwater inexplicably failed to control sufficiently for other factors that economists routinely use, namely experience and education, as public sector workers tend to have more experience and higher levels of education than the private sector. Throughout the Goldwater report, public and private sector workers are compared as if they were demographically identical. Such analysis is similar to someone presenting a chart comparing high school educated workers with college educated workers and decrying that college educated workers earn more.

Workers with higher education levels typically earn more than those with less formal education. Hence, when comparing public and private sector pay it is essential to take into account that the occupational and educational mix of these sectors are very different, with the public sector employing occupations which require much higher levels of education. On average, Arizona public-sector workers are more highly educated than private-sector workers; 43 percent of full-time Arizona public-sector workers hold at least a four-year college degree compared to 27 percent of full-time Arizona private-sector workers. Arizona state and local governments pay college-educated employees 28 percent less in annual compensation, on average, than private employers. The compensation differential is greatest for professional employees, lawyers, and doctors. On the other hand, the public sector appears to set a floor on compensation. The 20 percent of workers in state and local governments with only high school diplomas earn more than comparably educated workers in the private sector.

The mix of wages and non-wage benefits in the total compensation package also differs between private and public-sector full-time workers in Arizona. State and local government employees receive a higher portion of their compensation in the form of employer-provided non-wage benefits, and the mix of those benefits is different from the private sector.

Public employers like large private employers contribute a bigger portion of employee compensation to non-wage benefits. Retirement benefits are notably better in the public sector. Most public employees also continue to participate in defined benefit plans managed by the state, while most private sector employers have switched to defined-contribution plans, particularly 401(k) plans.

When employee characteristics and employer size are properly controlled for, Arizona full-time state and local employees are underpaid by 16.7 percent and undercompensated by 7.8 percent compared to equivalent private sector workers. Full-time public employees, however, work fewer annual hours, particularly employees with bachelors, masters, and professional degrees (because many are teachers or university professors). A re-estimated total compensation equation controlling for work hours of full-time employees demonstrates that Arizona public employees earn wages 14.3 percent less and 6 percent less in total compensation per hour than comparable full-time Arizona private-sector employees.

State employees are paid and compensated less than local government employees with state employees underpaid and under compensated 20.2 percent compared to 14.6 percent for local government employees, and the two groups are under compensated by 10.4 percent and 3.4 percent, respectively (see Figure 1).

Research Report

April 2, 2012

Are Arizona Public Employees Over Compensated?

Jeffrey H. Keefe, Ph.D.

Fellow, Grand Canyon Institute

Dave Wells, Ph.D.

Fellow, Grand Canyon Institute

Executive Summary

The research in this paper investigates whether Arizona public employees are overpaid at the expense of Arizona taxpayers. The Arizona legislature is considering four bills including one that would ban state and local governmental entities from recognizing public sector unions, prohibit collective bargaining, and meeting and conferring with union representatives. According to the bill’s proponents, taxpayers are unfairly burdened by public workers’ contracts negotiated by unions. Senator Rick Murphy, R-Peoria, who introduced Senate Bill 1485 prohibiting meetings with union representatives, declares that it is inappropriate when employees “take on the mantle of a public servant, then group up together and use leverage on the people they claim to serve.” He adds, “There needs to be a better balance” His statement suggests that state and local public employees in Arizona are excessively compensated.

Likewise, Governor Jan Brewer’s proposal to shift significant numbers of state employees to at will status, while couched in the context of more flexible pay, will reduce the attractiveness of state employment. If the state doesn’t meet market rates, the state will be increasingly challenged in hiring and retaining the best employees.

The data analysis presented in Figure 1 indicates that Arizona public employees, both state and local government employees, are not overpaid. Comparisons controlling for education, experience, hours of work, organizational size, gender, race, ethnicity, citizenship, and disability reveal that public employees in both state and local governments earn less than comparable private sector employees. On an annual basis, full-time Arizona state and local employees are under-compensated by 7.8 percent in comparison to otherwise similar private sector workers. When comparisons are made for difference in annual hours worked, full-time Arizona state and local employees are under-compensated by a smaller 6.0 percent.

These results sharply contrast with the analysis presented by the Goldwater Institute in their January 24 2012 policy report, which suggests that public unions caused Arizona state and local government worker compensation to be $560 million above market rate. Their analysis is inaccurate due to poor methodology.

Unlike the Goldwater analysis, our data set includes a random sample of 10,000 demographically detailed Arizona workers in both the public and private sector. The Goldwater Institute relied on statewide averages, so Arizona was but one point among all the states. In addition, Goldwater inexplicably failed to control sufficiently for other factors that economists routinely use, namely experience and education, as public sector workers tend to have more experience and higher levels of education than the private sector. Throughout the Goldwater report, public and private sector workers are compared as if they were demographically identical. Such analysis is similar to someone presenting a chart comparing high school educated workers with college educated workers and decrying that college educated workers earn more.

Workers with higher education levels typically earn more than those with less formal education. Hence, when comparing public and private sector pay it is essential to take into account that the occupational and educational mix of these sectors are very different, with the public sector employing occupations which require much higher levels of education. On average, Arizona public-sector workers are more highly educated than private-sector workers; 43 percent of full-time Arizona public-sector workers hold at least a four-year college degree compared to 27 percent of full-time Arizona private-sector workers. Arizona state and local governments pay college-educated employees 28 percent less in annual compensation, on average, than private employers. The compensation differential is greatest for professional employees, lawyers, and doctors. On the other hand, the public sector appears to set a floor on compensation. The 20 percent of workers in state and local governments with only high school diplomas earn more than comparably educated workers in the private sector.

The mix of wages and non-wage benefits in the total compensation package also differs between private and public-sector full-time workers in Arizona. State and local government employees receive a higher portion of their compensation in the form of employer-provided non-wage benefits, and the mix of those benefits is different from the private sector.

Public employers like large private employers contribute a bigger portion of employee compensation to non-wage benefits. Retirement benefits are notably better in the public sector. Most public employees also continue to participate in defined benefit plans managed by the state, while most private sector employers have switched to defined-contribution plans, particularly 401(k) plans.

When employee characteristics and employer size are properly controlled for, Arizona full-time state and local employees are underpaid by 16.7 percent and undercompensated by 7.8 percent compared to equivalent private sector workers. Full-time public employees, however, work fewer annual hours, particularly employees with bachelors, masters, and professional degrees (because many are teachers or university professors). A re-estimated total compensation equation controlling for work hours of full-time employees demonstrates that Arizona public employees earn wages 14.3 percent less and 6 percent less in total compensation per hour than comparable full-time Arizona private-sector employees.

State employees are paid and compensated less than local government employees with state employees underpaid and under compensated 20.2 percent compared to 14.6 percent for local government employees, and the two groups are under compensated by 10.4 percent and 3.4 percent, respectively (see Figure 1).

Introduction: The challenge to public employee compensation

According to Senator Murphy, public unions in a right work state such as Arizona, with 16 percent of public employees paying dues for representation, exert excessive influence on public officials resulting in excessive compensation. Is he right? Are Arizona public employees overpaid? What does a systematic evaluation show? Are state and local government employees overpaid to the detriment of Arizona taxpayers? Is there a cost to underpaying public employees? Could inadequate compensation hurt school performance or impair protective services? This research seeks to make a methodical and deliberate assessment of public employee pay to answer whether public employees are overpaid.

Making a comparison: Are Arizona public employees overpaid?

To answer whether Arizona public employees are overpaid, we need to ask two simple related questions: compared to whom? And compared to what? The standard of comparison for public employees is usually similar to private-sector workers, with respect to education, experience, and hours of work.

Ideally, we would compare workers performing similar work in the public sector with the private sector, but this is not always possible. There are too many critical occupations in the public sector—for example, police, fire, and corrections—without appropriate private-sector analogs. Even private and public teaching differs significantly. Public schools accept all students, while private schools are sometimes highly selective and may exclude or remove any poor performers, special needs, or disruptive students.

Consequently, instead economists compare workers with similar “human capital” or fundamental personal characteristics and labor market skills. These analyses based on personal characteristics comparisons capture most of the important and salient attributes observed in the comparable work studies. Prior research reveals that education level is the single most important earnings predictor. Education helps create work-relevant skills. People invest heavily in their own and their children’s education, by buying homes in communities with good schools and by paying or taking on debt to attend schools, colleges, and universities.

Empirically, education is followed by experience in advancing earnings. People learn by doing and by working in a variety of job tasks as they advance through occupational levels. Most occupations reward experience, since experience is associated with more competent and complex performance, arising from on-the-job learning. Other factors widely found to affect compensation include gender, race, ethnicity, and disability. By adding these other factors, productivity-related human capital differences are intermingled with labor market disadvantages stemming from historical patterns of discrimination and occupational segregation. We control for all these factors in our study.

When analyzing hours of work, most studies exclude part-time workers, since their hours vary; they earn considerably less than comparable full-time workers; they are more weakly attached to the labor force; and they often lack benefit coverage. This study follows standard practice by focusing on full-time public- and private-sector employees, who represent over 80 percent of the state’s labor force, and this study will control for hours worked per year. The study includes only year-round workers, who have worked a minimum of 1100 hours, which is often the minimum threshold to qualify for full employer provided benefits.

Our data from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series of the March Current Population Survey (IPUMS-CPS) enables researchers to control for the organizational size of each sampled full-time worker’s employer. An employer’s organizational size greatly influences employee earnings. The basic wage gap due to organizational size is 35 percent. Large firms with more than 500 employees comprise less than one third of one percent of all firms but provide jobs for nearly half of all private-sector employed persons. Large organizations employ more educated, experienced, and full-time workers; nonetheless, even after accounting for these factors, large organizations pay a premium. When we include benefits in the comparison, the compensation premium grows. Whereas the private sector has a relatively small number of large organizations, the public sector has relatively few small organizations. Nonetheless, over 67 percent of Arizona private sector employees work in organizations employing more than 100 employees, whereas 90 percent of public employees work in organizations with more than 100 employees.

Having decided who will be compared, the how do we next measure compensation? This is a more complex issue than it initially appears. Comparing wages is insufficient, since employee compensation increasingly includes employer-provided non-wage benefits. Regardless of how employees are paid—whether in wages or benefits—the essential issue in making a comparison is what does it cost a private- or public-sector employer to employ an employee. Employer costs may include not only wages, but paid time off for holidays, vacations, personal and sick days; supplemental pay including over time and bonuses; insurances, particularly health insurance but also life and disability insurance; retirement plan contributions, whether defined benefit or defined contribution including 401(k) plans; and legally mandatory benefit contributions such as unemployment insurance, Social Security, Medicare, disability insurance, and workers compensation. We then need to find the data that includes these employer costs.

To obtain wage and demographic data this study uses the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) of the March Current Population Survey (CPS). The CPS is a monthly U.S. household survey conducted jointly by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The March Annual Demographic File and Income Supplement is the most widely used source for earnings used by social scientists. For the purpose of comparability, the Arizona data excludes the self-employed and part-time, agricultural, and domestic workers. Because these are national survey-based data sets and Arizona has only about 1/50th of the nation’s population, the Grand Canyon Institute enhances the reliability of the sample by expanding the number of observations by ten years of data covering the years 2001 through 2011. Expanded Arizona samples reduce the survey margin of error, leading to more accurate estimates.

Hence, wage analysis should be interpreted as an average over the decade. No significant adjustment occurred during the decade for state and local government pay during the decade. As can be seen in Table 1 below, reproduced from the human resource office for the state of Arizona, state employees received modest raises until the economy sank and have been stagnant and declining since. Hence, using ten years of wage and salary data should fairly accurately represent the present situation of public earnings relative to the private sector.

To wages we need to add benefits. There is only one reliable source of benefit information in the United States, the Employer Costs for Employee Compensation (ECEC) survey, which is collected by the U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The ECEC includes data from both private industry and state and local government employees and provides data for private employers by firm size. Larger employers, over 500 employees, are significantly more likely to provide employees with benefits, in part, because they can spread administrative costs over a larger group and for insurance purposes, they can more readily diversify risks over a larger group. State and local governments resemble larger size private employers. The compensation cost analysis below control for employer size in making comparisons. Our data comes from the December 2010 survey, which yields compensation data across eight Mountain West states: Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico and Utah. Social Security and Pension public sector funding do vary across these states, so the study also makes adjustments to reflect Arizona compensation in the public sector.

The most important factor in earnings: Education level

Arizona public employees are substantially more educated than their private-sector counterparts. Approximately 43 percent of Arizona public employees hold a bachelors degree compared to 27 percent in the private sector. Higher educational levels are strongly associated with higher earnings in the labor market. Table 2, column 1, reports the returns to education in comparison to workers who have not completed high school. A high school graduate, all else equal, earns on average 27 percent more than some without a high school diploma. The education premium jumps to 47 percent on average if the worker attended some college, and if the worker holds an associate’s degree the return to education increases to 60 percent. Completing college with a bachelor’s degree yields an 87 percent premium, and a professional degree (law or medicine) increases average earnings by 150 percent compared to an individual without a high school diploma. A master’s degree yields an average 101 percent pay premium, and a doctorate produces a 132 percent return.

The public sector employs more highly educated workers. As private-sector organizations become larger, they also rely substantially more on educated labor. Smaller private-sector organizations employ more workers with a high school and less-than-high-school education than either larger private or state and local government. Only 4 percent of state and local government workers lack a high school education, whereas 17 percent of private-sector employees do not have a high school diploma in firms employing less than 100 employees, but the number falls to 7 percent with private employers with 500 or more employees.

| Table 2 Arizona Earnings Premium by Education and Distribution of Employee by Firm Type and Size |

|||||||

| Highest Degree Earned | Earnings Premium compared to Less than High School | All Private Employers | Private 1 to 99 Employees | Private 100 to 499 Employees | Private 500 and More Employees | Public Sector | |

| Less than high school | 0% | 12% | 17% | 15% | 7% | 4% | |

| High School | 28% | 28% | 30% | 26% | 25% | 20% | |

| Some College | 47% | 22% | 20% | 19% | 23% | 24% | |

| Associates | 61% | 10% | 8% | 11% | 11% | 8% | |

| Bachelors | 88% | 20% | 17% | 19% | 23% | 21% | |

| Professional Degree | 154% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 2% | |

| Masters | 102% | 6% | 3% | 5% | 7% | 17% | |

| Doctorate | 132% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 4% | |

| 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||

| Bachelors or more | 27% | 22% | 26% | 32% | 43% | ||

| Source: 2001-2011 CPS PUMS. Total observations 10,762 with 1,406 state and local government employees. | |||||||

The returns to education, however, are not equally distributed between the private and public sectors in Arizona. Table 3 provides computations of the annual earnings of full-time workers in Arizona by education attainment, comparing private sector and state/local sector employee wages and compensation. These comparisons do not adjust for the many factors we take into account in more refined analyses presented below (such as experience, annual hours worked, race, gender, etc.). The public sector has established a floor on earnings, allowing those with a high school education and those with some college (20 percent and 24 percent of state/local workers) to earn more than their private-sector counterparts (see Table 3). On the other hand, college educated public-sector employees earn considerably less than similarly educated private-sector employees.

| Table 3 Arizona Private and Public Sector Annual Earnings and Total Compensation |

||||

| Year – 1100+ Hours | Annual Wage Earnings | PublicPremium/Penalty | ||

| Full-Time | Private | Public | Public-Private | |

| Less than high school | $26,109 | $23,070 | -$3,039 | -12% |

| High School | $35,191 | $32,219 | -$2,972 | -8% |

| Some College | $41,399 | $36,650 | -$4,750 | -11% |

| Associates | $43,918 | $41,139 | -$2,780 | -6% |

| Bachelors | $69,178 | $43,873 | -$25,305 | -37% |

| Professional Degree | $118,421 | $84,830 | -$33,591 | -28% |

| Masters | $90,135 | $49,850 | -$40,285 | -45% |

| Doctorate | $76,905 | $62,504 | -$14,401 | -19% |

| All | $ 48,075 | $41,300 | -$6,776 | -14% |

| Total Compensation | PublicPremium/Penalty | |||

| Full-Time | Private | Public | Public-Private | |

| Less than high school | $31,472 | $31,205 | -$267 | -1% |

| High School | $43,914 | $45,938 | $2,024 | 5% |

| Some College | $52,357 | $53,708 | $1,352 | 3% |

| Associates | $57,258 | $56,160 | -$1,098 | -2% |

| Bachelors | $86,965 | $61,694 | -$25,270 | -29% |

| Professional Degree | $208,271 | $122,216 | -$86,055 | -41% |

| Masters | $105,217 | $71,349 | -$33,868 | -32% |

| Doctorate | $136,798 | $95,683 | -$41,115 | -30% |

| All | $60,375 | $58,879 | -$1,496 | -2% |

| Source: 2001-2011 CPS PUMS, December 2010 ECEC. Total observations: 10,762 with 1,406 state and local public employees. | ||||

A full-time worker with a high school education earns, on average, annual wages of 8 percent less when employed by state and local government compared to being employed by private sector. However, when we compare total compensation, a full-time worker on average with a high school education earns 5 percent more when employed by state and local government ($45,938) compared to the private sector ($43,914). High school graduates with some college experience approach total compensation equivalency between private and public sector. High school graduates with some college working for state and local government earn annual wages 11 percent less ($36,650) on average compared to ($41,399) workers employed by private employers, but when we compare total compensation public employees with a high school degree with some college earn 3 percent more than private sector workers. On average, workers with an associate’s degree face wages that are 6 percent less, respectively, than those of the same education level in the private sector, and 2 percent in total compensation.

This difference becomes even more significant as workers gain more education. On average, private sector employers pay workers with four year college degrees and advanced degrees substantially higher wages and compensation than do public sector employees. State and local workers with a bachelor’s degree make 37 percent less in salary and 29 percent less in total compensation—for those with a professional degree, the discrepancy rises to 28 percent less in salary and 41 percent less in total compensation. Workers with a master’s degree must face on average a 45 percent lower salary and 32 percent smaller total compensation, while those with a doctoral degree must face a 19 percent lower salary and 30 percent smaller total compensation. As we shall observe below, fewer average work hours in the public sector will reduce (by three to four percentage points) these large private sector wage premiums for college educated labor.

The growing role of non-wage benefits in employee compensation costs

Non-wage benefits, once referred to as fringe benefits, account for an increasing portion of employee compensation. Non-wage benefit growth is partially fueled by the tax deductibility of health insurance payments and pension contributions, allowing employers to compensate employees without either the employer or employee paying income tax at the time of compensation. Sometimes referred to as tax “efficient” compensation, the federal government foregoes $300 billion annually in income tax revenue to subsidize these benefits. Health insurance and pension benefits are particularly attractive to middle- and upper-income employees, who face higher marginal income tax rates.

Organizational size is the single strongest predictor of employee non-wage benefit participation and compensation. For example, employee participation in retirement plans varies considerably by organization size. Organizations with 1 to 99 employees have employee pension participation rates of 38 percent, organizations with 100 to 499 employees have participation rates of 64 percent, and organizations with 500 or more employees, 81 percent of employees participation in retirement plans. The pattern is similar for health insurance benefits. Organizations with 1 to 99 employees have employee participation rates in medical insurance of 43 percent, organizations with 100 to 499 employees have participation rates of 61 percent, and organizations with 500 or more employees, 71 percent of employees participate in medical insurance plans. This pattern is replicated for prescription drug and dental care plans.

Public-sector employees received more of their compensation in the form of non-wage benefits than private-sector workers. Table 4 provides the distribution of employer costs of compensation in June 2010. The Employer Costs for Employee Compensation (ECEC) survey provides the only valid and reliable estimate in the United States of non-wage benefit costs incurred by employers. It is conducted quarterly by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The ECEC includes data from both private industry and state and local government employees and provides data for private employers by firm size. This study uses these ECEC sample estimates from the Mountain Census Division to calculate relative non-wage benefit costs for private and public employees in Arizona. (Please see the Data Appendix for a more detailed description). Benefits’ costs range from 28.2 percent for small private employers to 32.3 percent for private employers with 500 or more employees, compared to 33.8 percent for state and local government employees. The compensation data reveal considerable variation within the private sector by organization size and between the private sector and state and local government compensation. However, large private sector employers most closely resemble public employers in the proportion of compensation devoted to benefits.

| Table 4 Employer costs per hour worked for employee compensation: Mountain Census Division |

|||||||||

| National Compensation Survey, December 2010 | |||||||||

| Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming | |||||||||

| Private industry | |||||||||

| 1-99 workers | 100 workers or more | ||||||||

| Compensation component | 1-99 workers | 1-49 workers | 50-99 workers | 100 workers or more | 100-499 workers | 500 workers or more | PublicSector | ||

| Total compensation | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| Wages and salaries | 71.8% | 71.7% | 72.1% | 71.0% | 74.2% | 67.7% | 66.2% | ||

| Total benefits | 28.2% | 28.3% | 27.9% | 29.0% | 25.8% | 32.3% | 33.8% | ||

| Paid leave | Summary | 5.4% | 4.7% | 7.2% | 7.6% | 7.2% | 7.9% | 6.9% | |

| Vacation | 2.9% | 2.3% | 4.2% | 3.9% | 3.7% | 4.0% | 2.5% | ||

| Holiday | 1.5% | 1.6% | 1.2% | 2.4% | 2.4% | 2.4% | 2.0% | ||

| Sick | 0.8% | 0.6% | 1.3% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 1.0% | 1.8% | ||

| Personal | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.6% | ||

| Supplemental pay | Summary | 5.6% | 7.3% | 1.8% | 2.4% | 1.9% | 2.9% | 0.7% | |

| Overtime and premium | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.4% | ||

| Shift differentials | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.1% | ||

| Non-production bonus | 4.9% | 6.6% | 1.0% | 1.3% | 1.0% | 1.7% | 0.3% | ||

| W2 Wages | 82.8% | 83.6% | 81.1% | 81.0% | 83.3% | 78.5% | 73.7% | ||

| Tax Free Benefits and Benefit Taxes | 17.2% | 16.4% | 18.9% | 19.0% | 16.7% | 21.5% | 26.3% | ||

| Insurance | Summary | 6.0% | 5.8% | 6.5% | 8.1% | 6.6% | 9.6% | 11.3% | |

| Life | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 1.6% | ||

| Health | 5.6% | 5.4% | 6.1% | 7.5% | 6.1% | 9.0% | 9.5% | ||

| Short-term disability | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.1% | ||

| Long-term disability | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.1% | ||

| ARIZONA | 7.5% | ||||||||

| Retirement and savings.. | Summary | 3.1% | 2.2% | 5.3% | 3.4% | 2.2% | 4.6% | 9.6% | |

| Defined benefit | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 1.4% | 0.8% | 2.0% | 8.9% | ||

| Defined contribution | 2.4% | 1.4% | 4.6% | 2.0% | 1.4% | 2.6% | 0.7% | ||

| ARIZONA | 6.2% | ||||||||

| Legally required benefits. | Summary | 8.0% | 8.4% | 7.1% | 7.6% | 7.8% | 7.3% | 5.4% | |

| Social Security and Medicare | 5.7% | 5.9% | 5.2% | 5.8% | 5.8% | 5.8% | 4.3% | ||

| Social Security | 4.5% | 4.7% | 4.0% | 4.6% | 4.6% | 4.7% | 3.2% | ||

| Medicare | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.1% | 1.0% | ||

| Federal unemployment insurance | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.0% | ||

| State unemployment insurance | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.2% | ||

| Workers’ compensation | 1.6% | 1.7% | 1.4% | 1.2% | 1.5% | 1.0% | 1.0% | ||

Public employees not only receive somewhat more of their compensation in benefits, but the mix of wages and benefits is different among paid leave, supplemental pay, insurances, retirement security, and legally mandated benefits. While overall paid leave costs are similar, private-sector employees receive more vacation pay while public employees receive greater sick leave compensation. Holiday and personal time compensation is similar. Public employees receive less than 1 percent of compensation in supplement pay, whereas private-sector employees in large organizations gain 3.3 percent of their earnings from supplemental pay, particularly bonuses. However, public employees receive considerably more of their compensation from employer provided health insurance. Health insurance accounts for 9.0 percent of private-sector compensation in organizations employing 500 employees or more but 9.5 percent of state and local government employee costs. Retirement benefits also account for a substantially greater share of public employee compensation: 9.6 percent compared to 4.6 percent in private sector organizations with more than 500 employees.

| Table 5 Arizona Retirement System Employer Contributions |

|||||

| Retirement System | Covers | Active Members | FY 2011 Employer Contribution Rate | FY 2011 Employer Contribution Normal Cost | Covered Salary (calculated from contributions) |

| ASRS | state, city, local employees, public school teachers (some charters don’t participate) | 223,323 | 9.85% | 6.66% | $8,480,960,680.20 |

| PSPRS | Police & Fire | 19,867 | 20.89% | 12.08% | $1,368,341,292.48 |

| CORP | Correctional Officers | 14,580 | 8.57% | 6.43% | $606,799,661.61 |

| EORP | Elected Officials | 857 | 29.79% | 18.51% | $73,657,559.58 |

| Total orWeighted Average | 258,627 | 11.35% | 7.43% | $10,529,759,193.88 | |

| Percent of Total Compensation | 7.5% | 4.9% | |||

| Source: Arizona State Retirement System, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report 2011, Arizona Public Safety Personnel Retirement System Consolidated Report, June 30, 2011, Arizona Corrections Officer Retirement Plan Consolidated Report, June 30, 2011, Arizona Elected Officials’ Retirement Plan Consolidated Report, June 30, 2011, | |||||

Arizona’s pension system has been a center of much concern, so the Grand Canyon Institute examined the state and local government contributions to the state’s major pension systems as seen in Table 5. The net employer contribution rate of 11.35 percent of salary which includes disability coverage translates when taken as a percent of total compensation as 7.5 percent, which appears in Table 4. It’s instructive to note that state and local governments as well as employees are currently contributing above normal costs to make up for a dreadful decade that saw large drops in the stock market just after 2000 and again in 2008, with the latter accompanied by drops in other asset prices as well. Employer contribution rates will continue to rise and in FY2013 it will be 13.4 percent or 8.9 percent if from total compensation. As we are doing an analysis of 2010 compensation we use figures from FY2011 in our analysis. Normal costs are what typically should be applied in these analyses, as normal costs are what contributions need to be to cover the future accrued liabilities of active members. However, as we have seen in the last decade if assets underperform, then normal costs are underestimated.

As with all benefits, the differences between private and public employees’ compensation costs shrink as the private organization comparison increases in size. Legally required benefits account for a greater share of the small employers’ compensation; as organizational size increases, these benefit costs decrease in relative importance. In local and government employment, legally required benefits represent a substantially smaller share of benefit costs for several reasons. Among the eight states in the Mountain Region from which compensation data derives, a in some states a significant number of public employees do not participate in Social Security which partially explains higher pension costs. These employees are not eligible for Social Security benefit payments at retirement unless they chose to work in another job elsewhere that is covered by Social Security. Second, the state and local governments do not participate in the federal unemployment system. Third, since the state and local governments offer more stable employment, they pay lower rates into the state unemployment insurance trust fund because unemployment insurance contribution rates are partially experience-rated. Arizona has 95.7 percent of its public employees covered by Social Security. This is in sharp contrast to Colorado (29 percent) and Nevada (18 percent) that are also included in the eight state regional data for compensation. Adjusting for the higher Arizona coverage means Arizona’s social security contribution should be 4 percent instead of 3.2 percent, making that category total 6.2 percent instead of 5.4 percent. That higher figure was highlighted in Table 4.

In summary, state and local government workers receive more of their compensation in employer-provided benefits. Specifically, public employers provide a greater share of their compensation in the form of employee health insurance and retirement benefits. Public employees receive less of their wages in the form of supplemental pay and have less costs for legally required benefits (financed through payroll taxes, such as worker compensation, unemployment insurance) than private-sector employees. To determine whether public employees are overpaid, the specific question that should be addressed is whether higher benefit costs more than they offset the lower wages paid to Arizona public employees. That is the question we turn to next.

Assessing private and public relative pay and benefits

To assess private and public relative employment costs we will use the micro data from the IPUMS-CPS, which provide us with a sample of Arizona employees with demographic characteristics including full-time status, education level, and years of experience, as a function of age, gender, race, disability, citizenship, employer organizational size, and industry. Compared to Arizona private-sector employees, Arizona state and local government employees on average are more experienced (22.4 years compared to 20.2 years); are more likely to be female (53 percent to 39 percent); work fewer weekly hours (42.9 to 43.2); are less likely to be black (4.3 percent to 3.7 percent); are less likely to be Asian (1.9 percent to 3.4 percent); and are less likely to be Hispanic (26.1 percent to 27.1 percent).

| Table 6 Arizona State and Local Government Employee CompensationRelative to Private Sector |

|||||||||

| 2001-2011 CPS PUMS December 2010 ECEC | Employees Annual Wages | Employees Hourly Wages | Employees Annual Total Compensation | Employees Hourly Total Compensation | |||||

| Arizona Public Employee | -16.70% | *** | -14.25% | *** | -7.73% | *** | -5.97% | *** | |

| State Gov Employee | -20.20% | *** | -18.57% | *** | -11.97% | *** | -10.35% | *** | |

| Local Gov Employee | -14.61% | *** | 12.76% | *** | -5.20% | ** | -3.36% | ||

| probability could equal 0 <.0001 *** <.01 ** <.05 * | |||||||||

| Full Time Workers | |||||||||

| Total observations 10,762 with 1,406 state and local public employees. | |||||||||

The Employer Cost of Employee Compensation data allow us to use the statistics on the benefit share of compensation by employer size to calculate total employer compensation costs for each employee in the sample. Table 6 reports the results of twelve earnings equations, estimating Arizona state and local government employee earnings compared to similar Arizona private-sector employees. Columns one and two provide estimates for employee wages. We find in column one that Arizona public employees (state and local government employees) have annual wage earnings at a statistically significant 16.7 percent less than comparable private-sector employees. In another estimate, separating state and local employees, we learn that state government employees have annual wage earnings 20.2 percent less and local government employee 14.6 percent less than private-sector employees. Column two provides hourly wage estimates. Using this comparison with private-sector employees, we learn that Arizona public employees have hourly wage earnings of 14.3 percent less than comparable private-sector employees. This breaks down into 18.6 percent less for state government employees and 12.8 percent less for local government employees (see Table 6).

When we compare total compensation between Arizona public and private employees, that earnings gap narrows but it does not disappear. Columns three and four report the estimates for total compensation. Reported in column three, Arizona public employees’ annual total compensation costs are 7.7 percent less than comparable private-sector employees. Arizona state employees receive total compensation of 12 percent less than private-sector employees, while local government employees earn 5.2 percent less. When we compare hourly estimates, the total compensation gap narrows but it remains both economically and statistically significant. Arizona public employees cost 6 percent less than comparable private-sector workers. State government employees’ total hourly compensation cost 10.4 percent less and local government employees cost 3.4 percent less than comparable private employees. In summary, these estimates show that Arizona state and local public employees earn significantly less in total hourly compensation than comparable Arizona private sector workers. Given the relatively large sample size and the statistical power the sample permits, this analysis concludes that Arizona public employees are modestly under-compensated in relation to comparable private-sector employees.

These are conservative estimates and likely understate the degree that public sector workers are undercompensated. Where we to add in Arizona specific adjustments for Social Security and for pensions for Fiscal Year 2011, the gap increases by an additional 1.4 percent. As although Arizona has higher social security contributions, it’s more than compensated by lower overall pension costs that are 2.2 percent less than the combined average for the eight states in the Mountain region of the census (see Table 4).

Census data backs up the contention that pension contributions in Arizona are lower than the other seven states collectively, as for 2009 pensions were 2.39 percent of wages and salary in Arizona, comparable to Montana, but significantly less than Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah. Only Wyoming contributed less.

Goldwater Institute’s Flawed Estimates on Impact of Unions

The Goldwater Institute has been claiming state and local governments could save $560 million by adopting legislation that prohibits governmental entities from recognizing or meeting with unions. If their estimate that each one percent decrease in union membership dropped average public sector compensation by about $135 were accurate, then public sector compensation (union and nonunion) would drop by 1.8 percent if the legislation had the impact of reducing union membership in Arizona from its current 16.6 percent of the public sector to the 9.1 percent found in the lowest state, North Carolina—which is one of the states touted by the Goldwater Institute.

However, having tested numerous specifications of their model, we have serious concerns with its use.

- Whereas the Grand Canyon Institute develops an estimate based on more than 10,000 demographically detailed workers from Arizona, the Goldwater Institute relied on statewide averages for all 50 states and the District of Columbia, which means they had only one data point from Arizona for each of their variables, yet they use it to make Arizona-specific estimates.

- Whereas the Grand Canyon Institute controls for worker experience, education, employer size, gender, ethnicity, disability, and even hours worked, the Goldwater Institute oddly enough only controls for two worker characteristics: pubic union membership and the extent to which the public sector employs more people with advanced degrees beyond a bachelors than the private sector in addition to private sector average compensation. They make no adjustment for differences in employment patterns between public and private sectors of college graduates, those with a high school degree or without a high school degree, nor do they control for differences in experience. From a human capital theory perspective, this is a strange regression—and when we added more appropriate controls to their model with aggregate state data, we found rather bizarre results, where more education meant less pay or more experience meant less pay. We expect this result is due to using statewide aggregates rather than individual workers, combined with the unique combination of specialty occupations like police officers, who typically only require a high school degree and are frequently also members of unions and have no fair private sector comparison.

Given that Arizona, outside of Virginia, is already in the lowest category of allowed collective bargaining (scoring 1 out of 3) in the Goldwater analysis, prudent policymakers would not rely on these estimates.

The broader literature highlighted in the Goldwater study purporting an 11 to 12 percent increase in unionized public sector worker compensation when appropriate demographic worker variables are controlled for should also be taken with caution. Arizona as a right to work state does not require employees to join a union, if union representation is voted for at a work site. Likewise, Arizona does not have mandatory collective bargaining. Instead governmental entities may voluntarily adopt “meet and confer” to develop proposals with union representatives that are not binding on the elected officials overseeing that governmental entity.

To estimate union wage effects, we examined two academic studies. One, by economist Henry Farber of Princeton had been cited by the libertarian Cato Institute in the context of how much public sector unions increased wages and salaries. Farber’s work broke down the impact of unions on wages by the legal framework imposed within the state. Arizona, as a state which does not require employees to join union, and has no state law requiring collective bargaining, falls in a weaker category, for which Farber using CPS data from 1983-2004, representing 376,000 workers, finds mixed results that suggest between a zero and seven percent wage premium for unionized workers, far less than what the Goldwater Institute asserted.

Bahman Bahrami, John D. Bitzan & Jay A. Leitch in their work note that public sector union wage premiums are significantly less than private sector ones. They estimate, using 2000-2004 CPS data, that nationwide it is about 11 percent. However, they find it varies across regions, lower in places with weaker union rights, and also lower for workers with higher education levels (white collar) like teachers and higher for blue collar workers (including police and fire fighters).

Collectively, these findings are consistent with what we estimate that showed larger gaps for higher educated workers compared to less educated workers, and, in fact, for some less educated workers public compensation exceeds the private sector. This is largely because the public sector competes for higher educated workers, and must enhance benefits to make up for less salary, and then needs to offer a relatively similar set of benefits to their other workers under principles of equity.

As a consequence, while unions may well exert upward pressure on wages, in Arizona, the Goldwater Institute and others are exaggerating that impact.

Conclusion: Are Arizona public employees overpaid? No

The earnings equation estimates indicate that Arizona public employees, both state and local government employees, are not overpaid. Rather, local and state public employees are under compensated. When we make comparisons controlling for education, experience, hours of work, organizational size, gender, race, ethnicity, citizenship, and disability, both state and local public employees earn less wages and compensation (including all benefits) than comparable private sector employees. The data analysis also reveals substantially different approaches to staffing and compensation between the private and public sectors, reflecting their differing occupations employed On average, Arizona public-sector workers are more highly educated than private-sector workforce; 43 percent of full-time Arizona public-sector workers hold at least four-year college degree compared to 27 percent of full-time private-sector workers. For college educated labor, Arizona state and local government pays significantly less than private employers. The earnings differential is greatest for professional employees, lawyers, and doctors. These earnings differences may create opportunities for cost saving by reviewing professional outsourcing contracts to examine what work might be performed by lower-cost public employees. The public sector boosts the financial stability of families of workers without a high school education, improving the earnings of workers without high school educations, when compared to similarly educated workers in the private sector.

Benefits are allocated differently between private and public-sector full-time workers in Arizona. State and local government employees receive a higher portion of their compensation in the form of employer-provided benefits, and the mix of benefits is different from the private sector. Public employers underwrite 33.8 percent of employee compensation in benefits, whereas private employers devote between 28.8 percent to 32.3 percent of compensation to benefits. Public employers provide more of their compensation in health insurance and pension benefits. Health insurance accounts for 5.6 percent to 9 percent of private sector compensation but 9.5 percent of state and local government compensation. Retirement benefits also account for a substantially greater share of public employee compensation, 9.6 percent compared to 2.2 percent to 4.6 percent in the private sector, although public sector employers save on Social Security payroll taxes because some of their employees are not covered. Public employees also continue to participate in defined benefit plans managed by the state (which the state has inadequately funded for over a decade), while private sector employers have switched to defined-contribution plans, particularly 401(k) plans.

On the other hand, public employees receive considerably less supplemental pay and vacation time, and public employers contribute significantly less to legally mandated benefits.

A standard earnings equation finds that full-time state and local employees are under-compensated by 7.7 percent. We observed, however, that public employees work fewer hours, particularly, employees with bachelor’s, master’s, and professional degrees. An earnings equation controlling for work hours of fulltime employees demonstrates that Arizona public employees earn 6 percent significantly lower compensation than comparable private sector workers with comparable annual hours worked.

Simply comparing private and public employee benefits leads to an obvious, but incorrect answer– public employees are overpaid, if we do not control for full-time workers. Table 3 in this paper shows that full-time public employee wages on average are $6,776 less annually than private sector wages and public sector employee total compensation is 2 percent less than private sector compensation. But such a comparison is still misleading because it does not make an apples-to-apples comparison: most critically, it does not control for the substantially higher level of education in the public sector. When we make the appropriate comparisons, large public employment wage and total compensation penalties emerge. Simple comparisons of private and public sector average wages are ill-informed, because the average public employee is considerably more educated than the average private sector worker.

Focusing on one or another component of compensation for comparison, misses the essential point that different employee groups have different preferences and respond differently to various mixes of compensation. For example, young people have a greater preference for cash, while older workers prefer retirement benefits. What citizens need to focus on in this debate is the cost of comparable levels of total compensation, controlling for education, experience, hours of work and other characteristics that influence employee productivity. When we look at overall compensation we learn that Arizona public employees pay for their better benefits through lower wages and salaries than comparable private sector employees.

Union status was omitted from this study on earnings comparisons, since it has been a focal point of the compensation controversy. This means that, in essence, we are statistically comparing public-sector workers, some of whom are union represented, with all private-sector workers—both union and nonunion—rather than with their union counterparts. Unionized private-sector workers have both better pay and higher benefits, of course, so our standard of comparison is very conservative. In other words, despite unionization, Arizona public sector workers are under-compensated. It is alleged that public employee unions and collective bargaining have produced an over-compensated workforce. Eligible public employees are weakly unionized in Arizona (approximately, 16 percent of public employees are members of a labor organization). It has been alleged by the Senator Murphy that they are the source of excessive compensation. It is a provocative hypothesis, but its main prediction has been shown to be incorrect by the research reported in this study—state and local government employees are not excessively compensated. This finding has now been replicated nationally in two other studies. Our analysis of other academic research indicates that claims of union power in Arizona are exaggerated.

Additionally it is well known that taxpayers do not want to pay higher taxes and so exert considerable pressure on elected representatives to resist increases in compensation, creating a formidable incentive and opportunity to hold government pay below market. Unionization represents a viable legal response to employer labor market power that benefits the state.

There is research evidence that under-compensating public employees can have adverse effects for citizens and on essential public services. A recent study shows that arrest rates and average sentence length decline, and crime reports rise when police pay is reduced or is viewed as unfair. These declines in performance are larger when the wage is set further from the police officers’ reference point. Education is the primary activity of state and local government. Approximately 54 percent of public employees work in education, from kindergarten through university. A current study of teacher performance by Craig Olson, who used unique data from Wisconsin and Illinois, reports that in higher paying districts, teachers were significantly more successful in raising student performance as measured on standardized tests, even after controlling all potential other plausible influences on scores. In short, public sector employee compensation matters to citizens not only as taxpayers but as consumers of critical services.

Public-sector workers’ compensation is neither the cause, nor can it be the solution to the state’s financial problems. Only an economic recovery can begin to plug the hole in the state’s budget. Unfortunately, the state’s own current budget balancing efforts may prolong the economic downturn by increasing unemployment and reducing demand for products and services. Thousands of Arizona public employees have lost jobs, and more will follow, causing their families to experience considerable pain and disruption. Others will have their wages frozen and benefits cut. Not because they did not do their jobs, or their services are no longer needed, or because they are overpaid. They too will join the list of millions of hard-working innocent victims of a financial system run amuck and economy operating far below full-employment. They do not deserve our anger or condemnation.

—Jeffrey H. Keefe, a Grand Canyon Institute Fellow, is associate professor of labor and employment relations at the School of Management and Labor Relations, Rutgers University, where he conducts research on labor markets, human resources, and labor-management relations to inform public policy. He teaches courses on collective bargaining, negotiations, financial analysis, benefits and social insurance, and strategic research. He is also a research associate at the Economic Policy Institute.

Dave Wells, a Grand Canyon Institute Fellow, holds a doctorate in Political Economy and Public Policy and has conducted numerous analyzes of state fiscal policies and labor market issues.

Reach the authors at JKeefe@azgci.org or DWells@azgci.org or contact the Grand Canyon Institute at (602) 595-1025.

The Grand Canyon Institute, a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, is a centrist think-thank led by a bipartisan group of former state lawmakers, economists, community leaders, and academicians. The Grand Canyon Institute serves as an independent voice reflecting a pragmatic approach to addressing economic, fiscal, budgetary and taxation issues confronting Arizona.

Grand Canyon Institute

P.O. Box 1008

Phoenix, AZ 85001-1008

GrandCanyonInstitute.org

Data Appendix

This study uses the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) of the March Current Population Survey (CPS). The CPS is a monthly U.S. household survey conducted jointly by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The March Annual Demographic File and Income Supplement is the most widely used source for earnings used by social scientists (King et al. 2009). This sample provides organizational size, a critical variable for our analysis of benefits. The sample is restricted to private sector and public sector state and local employees and excludes federal employees, the self-employed, and part-time, agricultural, and domestic workers. The IPUMS-CPS identifies an employee’s fulltime status, education level, experience level as a function of age minus years of education plus five, gender, race, employers’ organizational size, and industry. The IPUMS-CPS sample was selected for this analysis because the March CPS Annual File provides information on organizational size, not provided by the larger CPS sample in the Merged Outgoing Rotation Groups (MORG).

The Employer Cost of Employee Compensation (ECEC) data, part of the National Compensation Survey, was used to calculate total compensation costs as a markup on wages. Because the survey’s method of data collection is expensive, the sample is not sufficiently large enough to provide reliable state level benefit cost estimates. We would have preferred to analyze compensation costs by each state. The BLS did share their unpublished sample estimates for 10 major occupations by organizational sizes for private employers and state and local government in the East North Central Census division. This study uses these ECEC sample estimates to calculate relative benefit costs for each private and public employee in the sample. The calculation was done by calculating the relative benefit mark-up for each private-sector employee based on the size of organization that employs the individual and the employee’s occupation. State and local government employees’ wages were similarly marked up using an occupational benefit weight calculated using the ECEC data. It is assumed that when employees share information about their earnings they do not distinguish paid time off from time worked in salary data. Therefore paid time off is not included in the mark-up. CPS wages also include supplemental pay (Table A1). Specifically, this is a mark-up of total compensation relative to W-2 wages. This is the ECEC markup for benefits that is applied to Arizona worker wages to produce their total compensation estimates.

The IPUMS CPS sample for March 2001 to 2011 was used for the estimates, covering pay for the years 2000 through 2010. The sample size was 10,762 total observations and 1406 state and local public employee observations.

| Table A1Compensation Mark Ups for Class of Worker and Employer Type | ||||

| Private(number of employees) | ||||

| 1 to 99 | 100-499 | 500+ | Public | |

| All workers | 1.2265 | 1.1891 | 1.2749 | 1.3705 |

| Management, business, and financial | 1.1923 | 1.1718 | 1.2474 | 1.3047 |

| Professional and related | 1.2167 | 1.1159 | 1.2405 | 1.3485 |

| Sales and related | 1.1671 | 1.2815 | 1.3024 | 1.4453 |

| Office and administrative support | 1.1980 | 1.2301 | 1.2464 | 1.4134 |

| Service | 1.2842 | 1.2653 | 1.3414 | 1.4152 |

| Construction | 1.2501 | 1.2994 | 1.3244 | 1.4531 |

| Installation, maintenance, and repair | 1.2264 | 1.2384 | 1.2842 | 1.3830 |

| Production | 1.2608 | 1.3066 | 1.3569 | 1.4284 |

| Transportation and material moving | 1.2882 | 1.2645 | 1.2867 | 1.4313 |

| Source: December 2010 ECEC. Total observations 10,762 with 1,406 state and local public employees. | ||||