Policy Paper

October 10, 2018

Consequences of Prop. 126: $250 million cut to Education, Future cuts to Transportation Funding and Higher Taxes on Goods

Dave Wells, Ph.D., Research Director

Max Goshert, Sr. Research Associate

Executive Summary

Proposition 126 (Prop. 126), a constitutional amendment on November’s ballot, forbids state and local governments from creating new taxes or higher tax rates on services that were not already taxed as of December 31, 2017. Currently, Arizona exempts most services from taxation, but also taxes many services such as hotel stays, restaurants and bars.

Prop. 126 would impact any tax that is reauthorized, with one tax expiring replaced by a new version of the tax. The new version of the tax would be subject to the restrictions of Prop. 126. The education sales tax reauthorization is a good illustration. As noted by Michael Braun of the Arizona Legislative Council in a story in the Arizona Republic, “The existing (tax) is going to expire and the new one … will start after the expiration of the existing one — just a second or two, but still,” Braun said … “One expires, the next one kicks in…. Because that is a new tax, that requires Prop. 108.”[1]

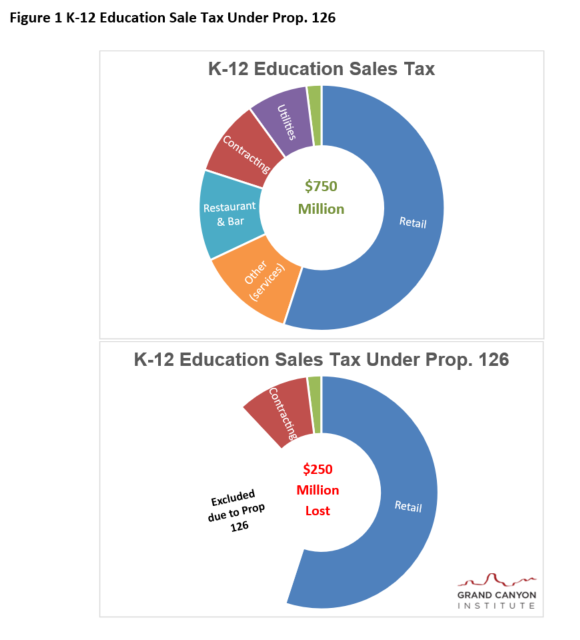

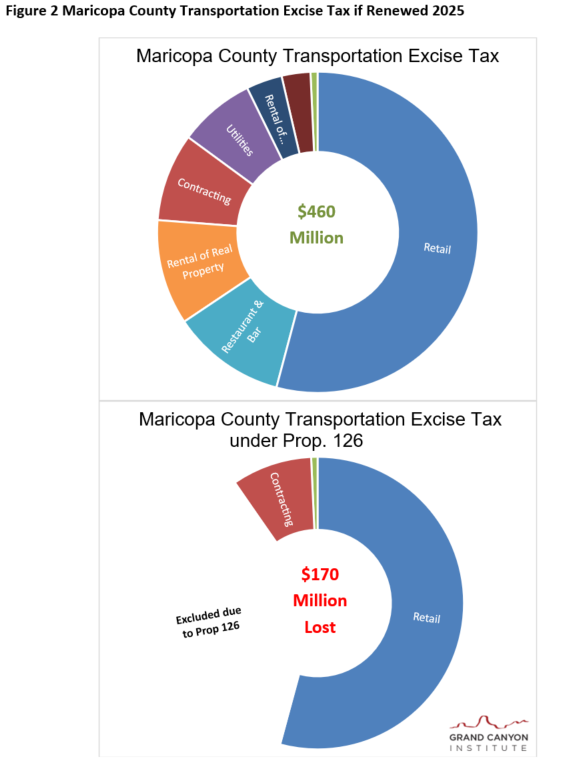

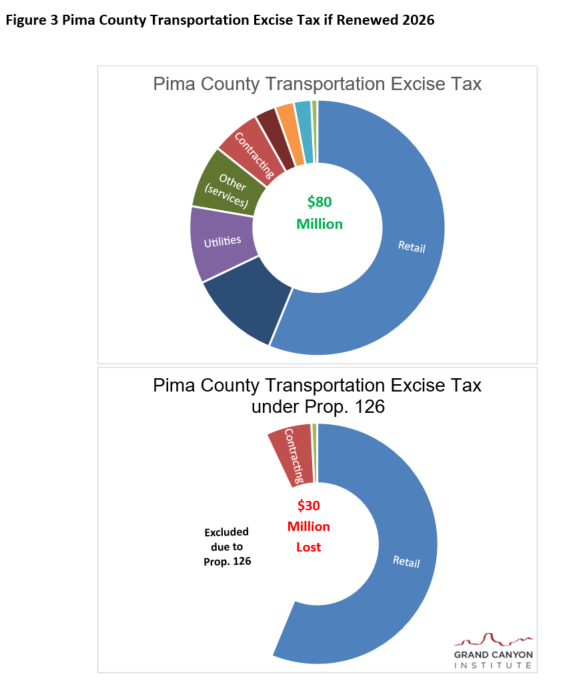

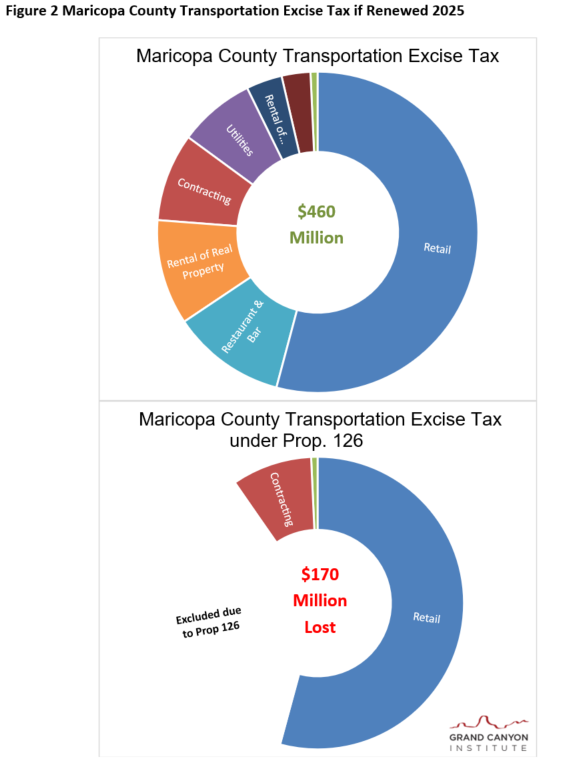

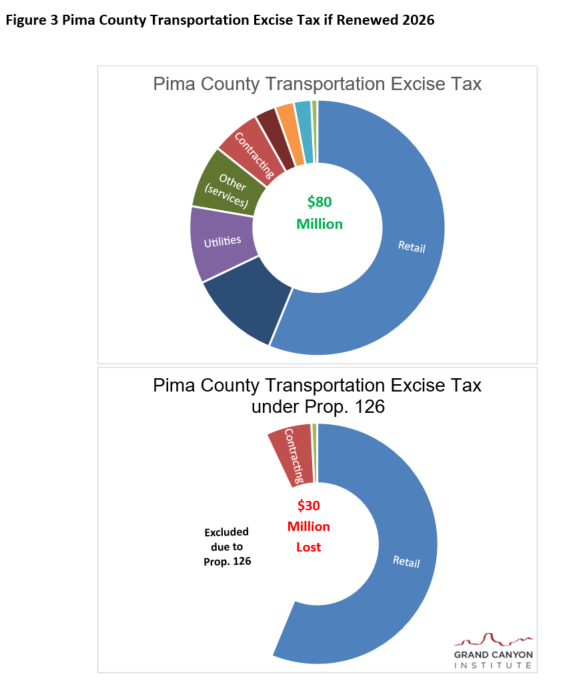

The Grand Canyon Institute estimates that the education sales tax renewal will lose one-third of revenues if Prop. 126 passes, which would currently amount to $250 million annually (See Figure 1). Likewise, counties that seek to reauthorize transportation taxes such as Maricopa by 2025 and Pima by 2026 would find that 36 percent of revenues are lost, necessitating a higher tax on goods with the heightened risk of voter disapproval (See Figures 2 and 3). Likewise, cities would find themselves in a similar predicament should they wish to increase or reauthorize any tax, as cities tax an even larger array of services than does state or county governments such as advertising and rental housing.

Likewise, efforts at the statewide level to better fund K-12 education have included proposals from business leaders to raise the education sales tax from 0.6 percent to 1.5 percent to provide an additional $1 billion for education and restore past funding. Under Prop. 126, the revenues would be reduced by one-third undermining the explicit aim of the proposal or necessitating that the tax rise to 2 percent instead.[2]

That proposal would need voter approval. That these tax increases go to voters anyway highlights an additional reason why Prop. 126 is unnecessary. Voters almost always have the final say on tax changes with rare exceptions. The only time since voters required a two-thirds vote of the legislature and signatures of the governor to increase taxes that process has occurred was this March when the legislature reauthorized the education sales tax and that only occurred because of the #RedforEd movement which had wide public backing.

Due to a declining base in goods as a portion of the economy as well as growth in service areas like financial services that are not taxed, the sales tax base has dropped from about 44 percent to 37 percent of state GDP over the last 20 years, which now leads to a net revenue loss to the state of more than $1 billion annually compared to what would have been generated two decades ago. That figure would be larger if losses to local governments were included.

If the state sales tax, technically known as a transaction privilege tax (TPT), were expanded to include services, the state could raise an additional $6.2 billion in revenues dedicated to education as well as the General Fund and improve sales collections by 90 percent.[3]

Alternatively, the state could reduce its rate of 5 percent and maintain the same education component of 0.6 percent. Reducing the base rate from 5 percent to 3 percent so the overall rate was 3.6 percent but adding to the base all service areas currently exempt would increase state revenues by $1.3 billion, which is twice the revenue that the proposed ballot initiative Invest in Ed would have generated for schools, $600 million of that comes from just applying the 0.6 percent education sales tax to exempt services. In addition, the city and county share of state sales tax revenue would rise an additional $190 million.

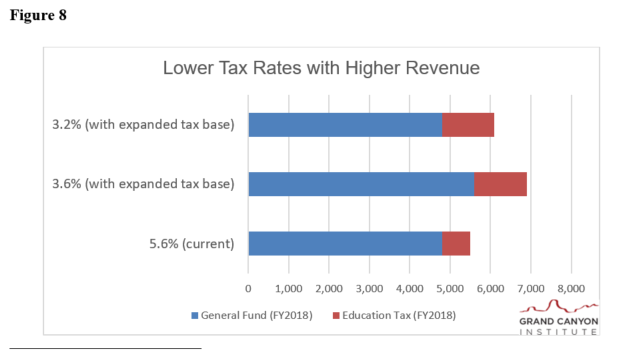

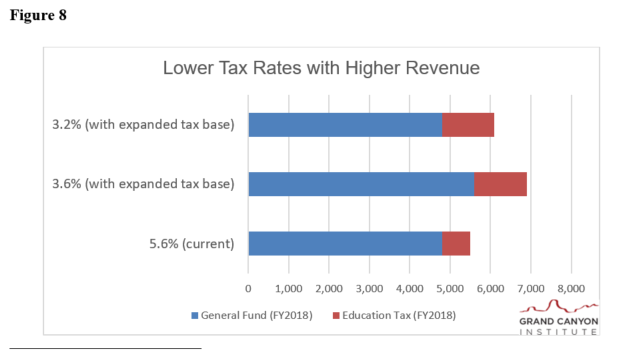

Lowering the state base sales tax rate from 5 percent to 2.6 percent would create a revenue neutral amount for the state’s General Fund if the tax base expanded to include currently exempt services. If the 0.6 education sales tax was retained with the base expanded to include exempt services the overall rate would be 3.2 percent instead of 5.6 percent with no change to the General Fund and an additional $600 million for K-12 education. See Figure 8 in the main paper for a graphical representation.

While voters may not presently wish to expand the TPT base to include all services, removing this option from policy options makes little sense, given the state’s overall revenue situation and the desire to provide added funds to public education.

If lawmakers wished to expand the sales tax base to include some or all services, they would in all likelihood refer a proposal to voters at which point voters could evaluate the relative benefits and costs of the proposal.[4] Prop. 126 proponents currently use innuendo about possible taxpayer costs without comparing to possible gains or admitting that voters would likely have final say on such changes. It is for these reasons that both major party Gubernatorial candidates Republican Governor Doug Ducey and Democratic challenger David Garcia both oppose Prop. 126.[5]

Background of Proposition 126

Proposition 126 amends the Arizona Constitution to restrict the state and municipal governments from imposing any tax on services which was not already in place as of December 31st, 2017.[6] The group which collected 406,000 signatures surpassing the 225,963 needed to get on the ballot is a political action committee (PAC) called the Citizens for Fair Tax Policy.[7] Currently, Arizona only taxes a limited number of services (60 as of 2007).[8] Most services, such as barber shops, fitness centers, and advertising, are not subject to the Transaction Privilege Tax (TPT).[9] The full Federation of Tax Administrators survey results for services taxed across the 50 states is in the appendix.

Prop 126 has been supported almost entirely by realtors. Citizens for Fair Tax Policy has collected $5.1 million from Arizona realtors through the Realtors Issues Mobilization Fund and another $1 million from the National Association of Realtors.[10] Out of 18 arguments for the measure that were published in the voter’s pamphlet distributed by the Arizona Secretary of State, twelve were written by realtors (only one of whom disclosed their profession). The argument that these groups make is that taxes on services will harm small business and low-income taxpayers.

While the vast majority of support comes from realtors, those opposed to the measure represent conservative, centrist, and liberal viewpoints. Opposition to Prop 126 includes the conservative Americans for Prosperity, the centrist Grand Canyon Institute (GCI) and Arizona League of Cities and Towns, and the liberal Arizona Center for Economic Progress and the affiliated Children’s Action Alliance. These groups make different forms of a similar argument, that the amount of goods consumed as a proportion of total consumption is declining, while service consumption is on the rise. The current TPT, which primarily taxes goods, is inequitable, because businesses who sell exempt services are not subject to the same treatment as those who sell goods. Buy clothes for your children and pay a tax. Get a manicure and a massage, no tax. In addition, all share the concern that Prop. 126, if passed, would cut education and transportation funding.

Prop. 126 Cuts K-12 Education $250 million annually

The current TPT (sales tax) primarily focuses on the goods sector. However, a significant portion already taxes services or areas that could be arguably put forward as services with the Arizona courts being forced to adjudicate. Current statute defines what is taxed but doesn’t use a goods and services demarcation. Prop. 126 as a Constitutional amendment has the potential to overturn any area in statute that could arguably put forward as a service. However, Prop. 126 does not define service. So for purposes of our analysis we use Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) categorization to differentiate goods from services. All of these areas that fall under services would have the tax rescinded when any tax came up for renewal or whose rate was increased. [11] Likewise, any municipality or locality that wished to add a small increment to their local sales tax would find that any areas that fall under services would be exempt from the tax. The consequence, is that tax renewals and new sales taxes would provide significantly less revenue than under current statute, between 33 and 40 percent less.[12]

Table 1 Goods and Services subject to current Sales (TPT) Taxation

The BEA classifications are listed in Table 1 along with corresponding areas currently taxed that would fall under each area. A wide range of services currently are taxed.

While Prop. 126 exempts services that are taxed as of December 31, 2017 at that level of taxation, it does not take into account when taxes expire and need to be reauthorized. For instance, SB1390 reauthorized the Education 0.6 percent sales tax from 2021 to 2041 because the original Prop. 301 authorization expires. Below is the language from the legislation:

From and after June 30, 2021 through June 30, 2041, in addition to the rate prescribed by subsection C of this section, an additional rate increment of six‑tenths of one percent is imposed and shall be collected. The taxpayer shall pay taxes pursuant to this subsection at the same time and in the same manner as under subsection C of this section. [13]

“From and after June 30,2021 …An additional rate increment” would be interpreted as a new tax by the language of Prop. 126. This is why a two-thirds vote was needed to renew it under Prop. 108. Consequently, the areas to be taxed under the renewal of the education sales tax would need to exclude any services in Table 1.

While this impact would not occur until July 2021, for purposes of comparison we use projected FY2019 revenues with and without Prop 126 to estimate the likely loss of revenue in current dollars. For the education tax extension one-third of revenues would be lost based on the TPT revenue breakdown reported in the JLBC 2018 Tax Handbook noted in Table 2. The handbook reports 15 percent of revenues as “other,” with no demarcation by category. Other (goods) include publication and job printing including photocopying as well as the tax on mineral mining (coal) and a value added (severance) tax on metallic mining such as copper. The other (service) category includes transient lodging (e.g., hotels), amusements (e.g., sporting events, movies), and rental of personal property (e.g., rental and leased vehicles). Data on the service side suggests that for the state transient lodging accounts for 2.4 percent. Data from Pima and Maricopa County implies rental of personal property may be 8 to 12 percent.[14] Pima data suggests communications could be an additional 2 percent. On the goods side, data for the state shows mining metals and minerals generate about 1 percent. Collectively these total around 15 percent and is not inclusive of all subcategories. GCI estimates 13 percent of other is services and the remaining 2 percent is goods. This means services encompass 33 percent or one-third of revenues for statewide sales taxes. When this 33 percent exclusion is applied, prospective Education sales tax revenues decrease $250 million annually.[15]

Table 2 Education Sales Tax Revenue Breakdown

| Category |

Portion of Revenues |

Impact of Prop. 126 |

| Retail |

55% |

Allowed |

| Contracting |

10% |

Allowed |

| Other (goods) |

2% |

Allowed |

| Utilities |

8% |

Prohibited |

| Restaurant & Bar |

12% |

Prohibited |

| Other (services) |

13% |

Prohibited |

Source: JLBC, 2018 Tax Handbook with other breakdown estimate from GCI.

Likewise, any future effort to use sales taxes to expand education funding further as had been advocated by some business leaders in the last year would face the same restriction. These leaders had advocated that the education sales tax should be increased from 0.6 percent to 1.5 percent to raise a billion dollars. Under Prop. 126, the rate would need to be 2 percent in order to generate the same amount of revenue. Figure 1 illustrates how the education sales tax or any state sales tax would be impacted by Prop. 126.

Figure 1 K-12 Education Sale Tax Under Prop. 126

Maricopa and Pima County Transportation Tax Renewals Reduced Nearly 40 Percent

The same logic applies to county transportation levies or any other tax that would need to be renewed. Maricopa county passed a half cent sales tax in 2004 and it expires in 2025. Pima County has a levy that expires in 2026. Should these counties seek reauthorization all service areas would be excluded, meaning they’d need to raise the tax on goods even higher to obtain the same level of funding. The net result is likely that taxes on goods would end up being 60 percent higher, rising from 0.5 percent to 0.8 percent to compensate for the funding loss. Consequently, since voters would focus more on the rate than the base, there would be a higher risk that voters would turn down much needed road and transportation improvement projects. The estimates for Maricopa County and Pima County are posted below in Figures 3 and 4. Though these impacts would not occur until 2025 and 2026, respectively, 2019 funding estimates are used to give a comparative sense of the impact. Likewise, while Pinal County recently passed a 0.5 percent 20 year transportation tax in 2017, if courts turn back a legal challenge to it, Pinal County may still lose one-third of the anticipated revenue if Prop. 126 passes because it did not go into effect until 2018, after the December 31, 2017 deadline in Prop. 126.[16] Yuma County has been planning to ask approval for a transportation tax and would face significant financial ramifications from the restrictions of Prop. 126.[17]

Table 3 Maricopa and Pima County Transportation Tax Breakdown

|

Maricopa County |

Pima County |

Under Prop. 126 |

| Retail |

61% |

56% |

included |

| Contracting |

10% |

6% |

included |

| Other (goods) |

1% |

1% |

included |

| Utilities |

9% |

10% |

prohibited |

| Communications |

In other (services) |

2% |

prohibited |

| Hotel/Motel |

In other (services) |

2% |

prohibited |

| Restaurant & Bar |

13% |

12% |

prohibited |

| Rental of Real Property |

12% |

In other (services) |

prohibited |

| Rental of Personal Property |

4% |

3% |

prohibited |

| Other (services)[18] |

3% |

8% |

prohibited |

Source: Rental of Personal Property from Arizona Dept. of Transportation, “Maricopa County Excise Tax: FY2017 Actual Revenue Distribution Flow;” Hammond, George and Alberta Charney (2017), “A Revenue Forecasting Model for the Pima RTA: updated to 2016,” Economic and Business Research Center, Eller College of Management, University of Arizona, March with GCI estimate for breakdown between goods and services of other.

Figure 2 Maricopa County Transportation Excise Tax if Renewed 2025

Figure 3 Pima County Transportation Excise Tax if Renewed 2026

Declining Sales Tax Base Already Costs the State $1 Billion Annually

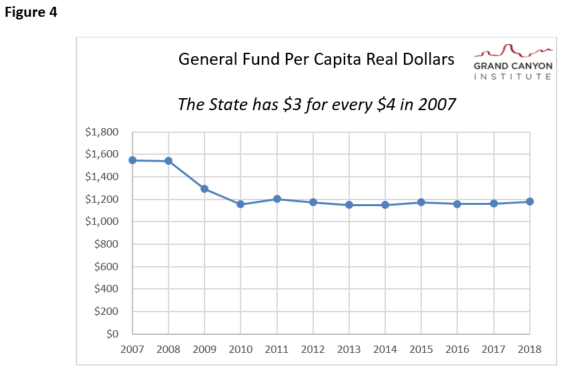

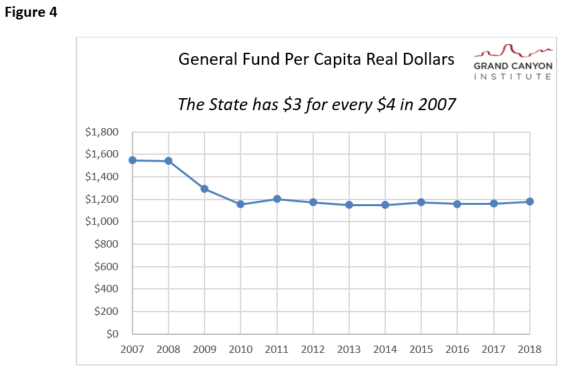

Recently state revenues have been improving so that Governor Ducey was able to fund an approximately 20 percent raise for teachers by 2020. The bigger picture for the state shows continuing challenges with state revenues compared to before the Great Recession. According to a 2017 report by GCI, Arizona faces close to a $5 billion deficit relative to state revenue in fiscal year (FY) 2007.[19] Put in perspective, adjusted for inflation and population, the state only has $3 for every $4 that it had ten years ago, a 25 percent decline, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4

One of the contributors to this decline has been the declining tax base of Arizona’s Transaction Privilege Tax (TPT), otherwise known as a sales tax. The state currently imposes a 5 percent sales tax that goes about 80 percent to the General Fund and the rest to cities and counties along with a 0.6 percent sales tax that funds education—which the legislature renewed for another 20 years earlier this year and would lose one-third of funding if Prop. 126 passes.

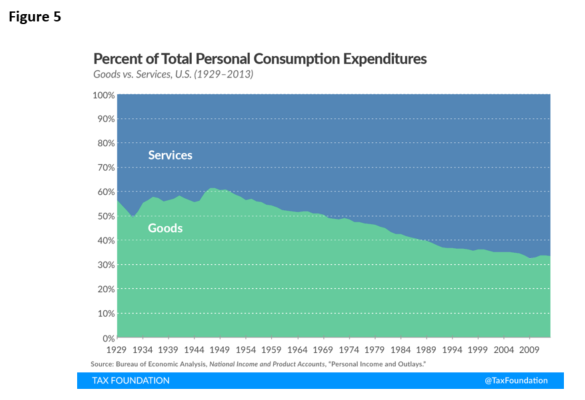

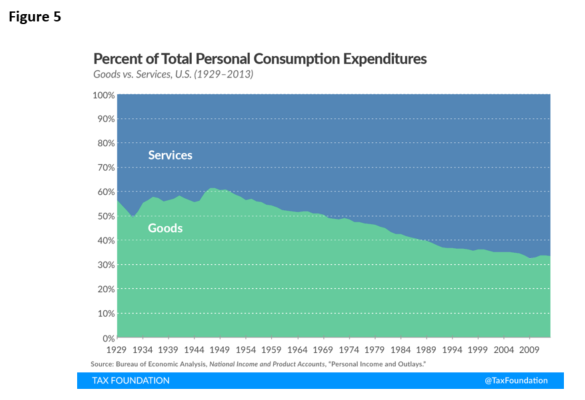

Services have been growing as a portion of the economy. Across the nation as a whole, the consumption of goods as a percentage of total personal consumption expenditures has fallen from over 50 percent in the early 1930s to just over 30 percent today. See Figure 5.[20]

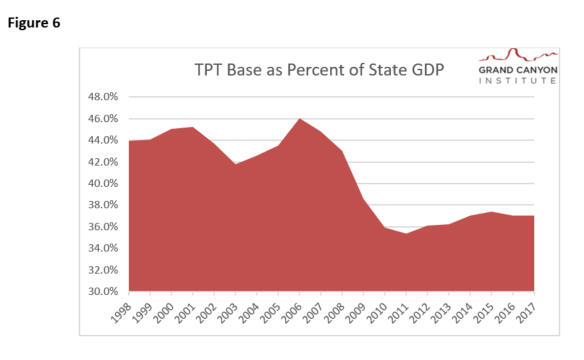

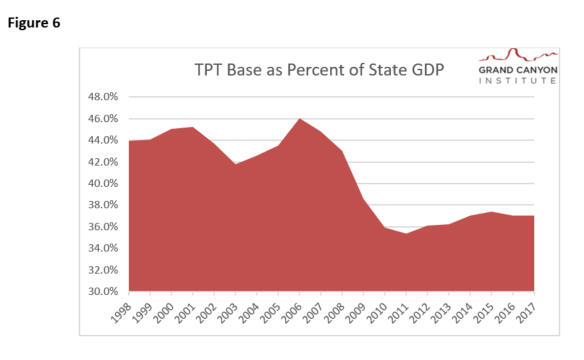

However, as noted earlier in the report large sections of Arizona’s sales tax covers services as well as goods. But some of the areas with the greatest growth have been in areas like professional services, health care services and financial services that are currently exempt from taxation. Consequently, over the last 20 years the portion of the Arizona economy covered by sales taxes has declined. The average coverage from 1998 through 2002 (5 years) was 44 percent. Today the coverage has dropped one-sixth to 37 percent.[21] See Figure 6.

Figure 5

Figure 6

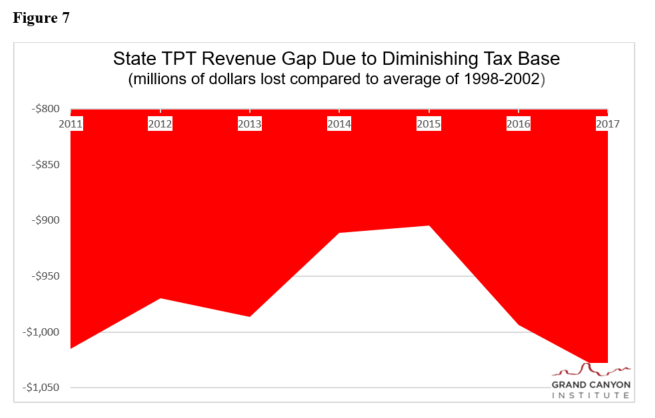

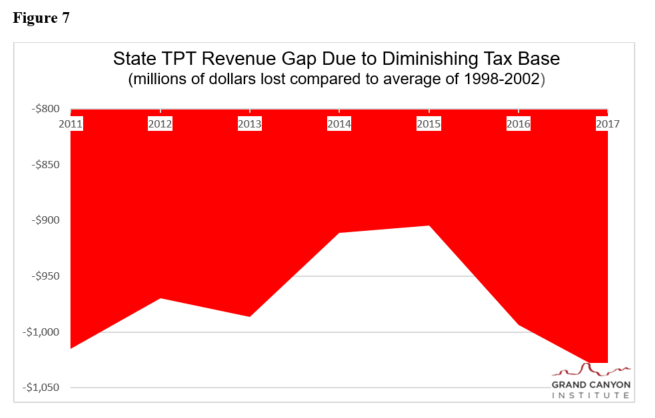

The net effect is a decline in revenues. If the state was still able to collect sales taxes on 44 percent of GDP (the average of 1998-2002), the state would have $1 billion more in revenue than it does today as shown in Figure 7. Consequently, the state as well as local governments are under pressure to raise the sales tax to sustain revenue. Prop. 126 would lead to even higher taxes on businesses selling goods.

Figure 7

Across Arizona TPT varies from 5.6 percent to 11.2 percent depending on where in Arizona the transaction occurs.[22] In Phoenix, for example, the total TPT rate is 8.6 percent. The state average combined rate is 8.38 percent. Overall, Arizona ranks 28th for its state sales tax rate out of all other states and the District of Columbia. However, it ranks 11th highest when the average combined rates are factored.[23]

Prop. 126 Forestalls Option of Expanding the Sales Tax Base

If the state sales tax, technically known as a transaction privilege tax (TPT), were expanded to include services, the state could raise an additional $6.2 billion in General Fund and dedicated education revenues and improve sales tax collections by 90 percent.[24]

Alternatively, the state could reduce its rate of 5 percent and maintain the same education component of 0.6 percent. Reducing the base rate from 5 percent to 3 percent so the overall rate was 3.6 percent but adding to the base all service areas currently exempt would increase state revenues by $1.3 billion, which is twice the revenue that the proposed ballot initiative Invest in Ed would have generated for schools, $600 million of that comes from just applying the 0.6 percent education sales tax to exempt services. In addition, the city and county share of state sales tax revenue would rise an additional $190 million.

Lowering the state base sales tax rate from 5 percent to 2.6 percent would create a revenue neutral amount for the state’s General Fund if the tax base included currently exempt services. If the 0.6 education sales tax was retained with the base expanded to include services the overall rate would be 3.2 percent instead of 5.6 percent with no change to the General Fund and an additional $600 million for K-12 education. These results are summarized in Figure 8 below.

Figure 8

Conclusion

Prop. 126 creates an unnecessary constitutional obstacle to tax reform or investing in education. In 1992, Arizona voters passed Proposition 108 (Prop 108) which added a provision to the state constitution that required a 2/3 vote by the House and Senate for any bill which attempted to impose new taxes or increase existing taxes.[25] Because of this law, most tax increases now occur through ballot measures, either by the public via citizens initiatives or by the Legislature through ballot referrals (which is not subject to the same restrictions). The only sales tax increase that has occurred since Prop 108 was passed was the reauthorization of the education tax from Prop. 301, which was passed via a ballot initiative and extended by a 2/3 vote in the Legislature in March. [26]

That Prop. 108 applied to this reauthorization indicates it is a new tax and thus subject to Prop. 126, if it passes. GCI estimates that if Prop 126 is approved that the dedicated education tax will have one-third less revenues or $250 million less dollars annually once the renewal begins in Fiscal Year 2022.

Likewise, transportation levies will lose 36 percent of their current tax base, leading to substantial losses of revenues on reauthorization or a need to increase the rate from half a percent to 0.8 percent to compensate, which in turn risks a greater change of voter rejection, as voter’s will tend to focus more on the rate than the tax base.

Prop. 126 enables the continued decline in the sales tax base which is already costing the state more than $1 billion annually compared to two decades ago. Prop. 126 also interferes with discussions to reduce the overall sales tax on goods while extending the base to include services. As noted in this analysis lowering the state sales tax with the Prop. 301 education increment from 5.6 percent to 3.6 percent but expanding the base to include services would generate an additional $1.3 billion to the state that could be invested in public education. $600 million alone would come from expanding the 0.6 education sales tax to services. Local governments would receive $190 million.

Both Republican Doug Ducey and Democrat David Garcia reject Prop. 126, so should voters on November 6th.

Dave Wells holds a doctorate in Political Economy and Public Policy and is the Research Director for the Grand Canyon Institute, a centrist fiscal policy think tank founded in 2011. He can be reached at DWells@azgci.org or contact the Grand Canyon Institute at (602) 595-1025, ext. 2.

Max Goshert is completing his masters degree in Public Policy at Arizona State University. He can be reached at MGoshert@azgci.org.

The Grand Canyon Institute, a 501(c) 3 nonprofit organization, is a centrist think tank led by a bipartisan group of former state lawmakers, economists, community leaders and academicians. The Grand Canyon Institute serves as an independent voice reflecting a pragmatic approach to addressing economic, fiscal, budgetary and taxation issues confronting Arizona.

Grand Canyon Institute

P.O. Box 1008

Phoenix, Arizona 85001-1008

GrandCanyonInstitute.org

Appendix

| State Taxation of Services by Category – 2017 |

| # of Service Taxed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fabrication, |

|

|

|

|

Personal |

Business |

Computer |

Online |

Admissions/ |

Prof. |

Repair & |

Other |

|

|

Utilities |

Services |

Services |

Services |

Services |

Amusements |

Services |

Installation |

Services |

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Alabama |

12 |

1 |

6 |

3 |

6 |

10 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

42 |

| Alaska |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

| Arkansas |

16 |

7 |

12 |

1 |

0 |

12 |

0 |

11 |

14 |

73 |

| Arizona* |

12 |

2 |

7 |

0 |

5 |

9 |

0 |

2 |

23 |

60 |

| California |

2 |

2 |

7 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

5 |

21 |

| Colorado |

4 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

19 |

| Connecticut |

10 |

9 |

21 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

0 |

10 |

25 |

99 |

| Delaware |

9 |

20 |

34 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

9 |

19 |

37 |

152 |

| Dist. of Columbia |

14 |

9 |

17 |

6 |

4 |

10 |

0 |

14 |

17 |

91 |

| Florida |

9 |

4 |

11 |

0 |

2 |

13 |

0 |

15 |

15 |

69 |

| Georgia |

10 |

4 |

5 |

2 |

0 |

8 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

36 |

| Hawaii |

16 |

20 |

34 |

8 |

6 |

14 |

9 |

18 |

42 |

167 |

| Idaho |

0 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

4 |

9 |

0 |

6 |

4 |

30 |

| Illinois |

12 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

9 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

29 |

| Indiana |

12 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

36 |

| Iowa |

10 |

15 |

17 |

0 |

1 |

13 |

0 |

13 |

20 |

89 |

| Kansas |

10 |

10 |

9 |

1 |

1 |

13 |

0 |

15 |

15 |

74 |

| Kentucky |

11 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

6 |

8 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

40 |

| Louisiana* |

10 |

8 |

5 |

3 |

5 |

9 |

0 |

13 |

7 |

60 |

| Maine |

10 |

1 |

6 |

0 |

5 |

3 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

33 |

| Maryland* |

5 |

3 |

13 |

1 |

0 |

11 |

0 |

4 |

3 |

40 |

| Massachusetts* |

9 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

19 |

| Michigan |

12 |

2 |

7 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

27 |

| Minnesota |

15 |

8 |

11 |

0 |

6 |

12 |

0 |

6 |

9 |

67 |

| Mississippi |

10 |

5 |

8 |

3 |

7 |

11 |

0 |

13 |

22 |

79 |

| Missouri |

8 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

24 |

| Montana |

12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

17 |

| Nebraska |

14 |

10 |

14 |

3 |

6 |

12 |

0 |

12 |

10 |

81 |

| Nevada |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

0 |

2 |

7 |

21 |

| New Hampshire |

6 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

9 |

| New Jersey |

12 |

6 |

17 |

1 |

4 |

7 |

0 |

15 |

22 |

84 |

| New Mexico* |

16 |

20 |

32 |

8 |

6 |

14 |

9 |

18 |

41 |

164 |

| New York |

5 |

5 |

13 |

1 |

1 |

6 |

0 |

14 |

19 |

64 |

| North Carolina |

12 |

7 |

8 |

0 |

6 |

9 |

0 |

14 |

6 |

62 |

| North Dakota |

4 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

22 |

| Ohio |

8 |

11 |

14 |

5 |

8 |

13 |

0 |

11 |

16 |

86 |

| Oklahoma* |

9 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

33 |

| Oregon |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

| Pennsylvania |

9 |

5 |

16 |

4 |

8 |

2 |

0 |

14 |

9 |

67 |

| Rhode Island |

11 |

1 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

3 |

8 |

37 |

| South Carolina |

4 |

6 |

7 |

4 |

2 |

10 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

39 |

| South Dakota |

14 |

19 |

28 |

8 |

8 |

13 |

5 |

18 |

39 |

152 |

| Tennessee |

11 |

10 |

7 |

3 |

6 |

12 |

0 |

14 |

13 |

76 |

| Texas |

12 |

10 |

14 |

8 |

8 |

12 |

1 |

10 |

15 |

90 |

| Utah |

7 |

8 |

6 |

0 |

5 |

11 |

0 |

15 |

12 |

64 |

| Vermont |

9 |

2 |

5 |

1 |

6 |

11 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

37 |

| Virginia |

1 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

4 |

17 |

| Washington |

16 |

20 |

33 |

8 |

8 |

13 |

9 |

16 |

44 |

167 |

| West Virginia |

8 |

18 |

27 |

4 |

5 |

13 |

1 |

13 |

26 |

115 |

| Wisconsin |

11 |

10 |

8 |

3 |

7 |

14 |

0 |

13 |

16 |

82 |

| Wyoming |

10 |

7 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

0 |

16 |

13 |

66 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total # in Category |

16 |

20 |

34 |

8 |

8 |

15 |

9 |

19 |

47 |

176 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| * No response, 2007 data reported |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Source: FTA, Taxation of Services Survey, 2017. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| # States tax more than one-half of the services |

35 |

8 |

7 |

9 |

25 |

34 |

5 |

25 |

7 |

|

[1] Sanchez, Yvonne Wingett (2018), “Doug Ducey to sign tax measure—is he violating his pledge to never raise taxes?” Arizona Republic, March 22, https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/politics/legislature/2018/03/22/pressure-mounting-doug-ducey-break-his-pledge-never-raise-taxes/448003002/. Prop. 108 requred two-thirds approval in both chambers to implement a new tax.

[2] 0.2 percent increase to cover lost revenues from Prop. 301 reauthorization plus 0.3 percent increase to cover lost revenues from an increase from 0.6 to 1.5 percent.

[3] Office of Economic Research and Analysis and Arizona Department of Revenue. (2017). The revenue impact of Arizona’s tax expenditures fiscal year 2016/2017. Retrieved from https://azdor.gov/sites/default/files/media/REPORTS_EXPENDITURES_2017_fy17-preliminary-tax-expenditure-report.pdf. GCI adjusts the figure by an additional 6% to yield an estimate for FY2018 which was the overall growth in TPT.

[4] Alternatively, lawmakers would need a two-thirds vote in the House and Senate and the Governor’s consent. The only time this alternative has occurred in the last 25 years was earlier this year to extend Prop. 301 when thousands of teachers were protesting at the state capitol.

[5] Fischer, Howard (2018), “Arizona’s Prop. 126-a ban on taxing services-draws a diverse resistance,” Arizona Daily Star, Oct 1, https://tucson.com/news/local/arizona-s-prop-a-ban-on-taxing-services-draws-diverse/article_b133e82e-2887-5415-b08f-85f39ad7d657.html

[6] The Protect Arizona Taxpayers Act: Ballot measure, Arizona. (2018). Retrieved from https://protectaztaxpayers.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Ballot_Initiative_Text.pdf.

[7] @SecretaryReagan. (2018, July 3). The 1st of the ballot measure committees (Citizens for Fair Tax Policy) has filed signatures. They’ve reported 406K signatures. We have 20 biz days to process the petitions then counties have 15 to verify a sample of the signatures. http://www.Arizona.Vote for more information [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/SecretaryReagan/status/1014235169140510720.

[8] Federation of Tax Administrators. (2017, July-August). FTA survey of services taxation – update. Retrieved from https://www.taxadmin.org/btn-0817_services. Arizona did not participate in the 2017 survey update, so the data from Arizona is from 2007.

[9] Fischer, H. (2018, March 12). Realtors seek ballot measure to ban taxation of services. Arizona Capitol Times. Retrieved from https://azcapitoltimes.com/news/2018/03/12/realtors-seek-ballot-measure-to-ban-taxation-of-services/. Advertising is taxed by most cities, however.

[10] Randazzo, R. (2018, September 13). Prop. 126 tax-measure ads are all over Phoenix airwaves – here’s who is behind them. AZ Central. Retrieved from https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/politics/elections/2018/09/13/arizona-proposition-126-ballot-measure-backed-real-estate-interests/1194565002/.

[11] Arizona Dept. of Revenue, “Arizona State, City and County Transaction Privilege and Other Tax Rate Tables,” Effective Oct. 1, 2018, https://azdor.gov/sites/default/files/media/TPT_RATETABLE_10012018.pdf.

[12] Calculations in this paper range from 33 to 37 percent, but because cities typically also tax the service areas of advertising and residential rental units, their portion of service is higher.

[13] Fifty-third Legislature, Second Regular Session, 2018, Chapter 74, Senate Bill 1390, https://www.azleg.gov/legtext/53leg/2R/laws/0074.htm.

[14] Rental of Personal Property from Arizona Dept. of Transportation, “Maricopa County Excise Tax: FY2017 Actual Revenue Distribution Flow;” https://azdot.gov/docs/default-source/businesslibraries/rarftankchart_17.pdf?sfvrsn=4; Hammond, George and Alberta Charney (2017), “A Revenue Forecasting Model for the Pima RTA: updated to 2016,” Economic and Business Research Center, Eller College of Management, University of Arizona, March, http://www.rtamobility.com/documents/pdfs/RTATMC/2017/RTATMC-2017-08-28-Item-3D-FinalReportRTA-2017-3-28.pdf.

[15] Assumptions made. FY2019 projection based on 5% real growth over FY2018. Mining data is from Ginsberg, Robert (2008), “Mining Taxes in Ten Western States,” Center on Work and Community Development, April, http://equalitystate.org/assets/pdfs/reports/Western_mining_and_taxes_report.pdf. Transient lodging data from Hazinski, Thoasm et al. (2016), “2016 HVS Lodging Tax Report-USA,” HVS, August https://www.hotelnewsresource.com/pdf16/HVS082916.pdf. Rental of Personal Property from Arizona Dept. of Transportation, “Maricopa County Excise Tax: FY2017 Actual Revenue Distribution Flow,” https://azdot.gov/docs/default-source/businesslibraries/rarftankchart_17.pdf?sfvrsn=4. Data from sources adjusted at times for portion going to the state, e.g., mining was adjusted for state shared revenue.

[16] Kincaid, Jake (2018), “Tax Court rules Pinal County transportation tax is illegal,” Arizona City Independent, Aug. 2, https://www.pinalcentral.com/arizona_city_independent/news/tax-court-rules-pinal-county-transportation-tax-is-illegal/article_3b3d04aa-ee27-5ee1-ad50-910f22e5cc92.html. The issue is whether or not voters were informed the tax would extend beyond the retail classification. The Arizona Department of Revenue indicates that the TPT base for Pinal’s transportation tax would match up with the state’s TPT base, so the revenue loss under it would be one-third. Arizona Dept. of Revenue, “Pinal County Transportation Tax Begins April 1, 2018,” https://azdor.gov/news-events-notices/news/pinal-county-transportation-tax-begins-april-1-2018.

[17] Pinal County collections started this year, after Dec. 31, 2017. It’s possible a legal challenge could be mounted regarding services—(I should check this!).

[18] For Pima County this category includes Commercial Leases (Real Property). For Maricopa County this category includes Hotel/Motel and Communications.

[19] Wells, D. (2018a). State of the state budget 2018: The revenue system is broken. Grand Canyon Institute. Retrieved from https://grandcanyoninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/GCI_Policy_State_of_the_State_Budget_2018_1-08-2018-.pdf.

[20] Drenkard, S. (2017, February 10). Three big problems with sales tax today – and how to fix them. Tax Foundation. Retrieved from https://taxfoundation.org/three-big-problems-sales-tax/.

[21] TPT Base is calculated based on General Fund dollars divided by 78 percent (approx. portion to the state) divided by 5 percent. TPT is used interchangeable with sales tax in the discussion.

[22] Avalara. (2018). Arizona sales tax basics. Retrieved from https://www.avalara.com/taxrates/en/state-rates/arizona.html

[23] Walczak, J., and Drenkard, S. (2018, May 16). State and local sales tax rates, midyear 2018. Tax Foundation. Retrieved from https://taxfoundation.org/state-local-sales-tax-rates-midyear-2018/.

[24] Office of Economic Research and Analysis and Arizona Department of Revenue. (2017). The revenue impact of Arizona’s tax expenditures fiscal year 2016/2017. Retrieved from https://azdor.gov/sites/default/files/media/REPORTS_EXPENDITURES_2017_fy17-preliminary-tax-expenditure-report.pdf. GCI adjusts the figure by an additional 6% to yield an estimate for FY2018 which was the overall growth in TPT.

[25] Hoffman, J. (2011). Prop 108: Putting the brakes on state tax increases. League of Arizona Cities and Towns. Retrieved from http://www.leagueaz.org/connection/2011/0711/index.cfm?a=prop108.

[26] Cano, R. (2018, March 22). Arizona Legislature passes education sales tax plan. AZ Central. Retrieved from https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/politics/arizona-education/2018/03/22/arizona-lawmakers-fast-track-proposition-301-education-sales-tax-extension/447963002/.

Budget

Budget