Policy Analysis

April 24, 2018

(download pdf with embedded links to sources)

Getting Serious about K-12 Educational Goals Costs $2 Billion Annually

Dave Wells, Ph.D.

Research Director, Grand Canyon Institute

In two short months the #REDforED movement has already successfully pressured the legislature to pass a 20-year extension of the 0.6 percent education sales tax and moved Governor Doug Ducey from a 1 percent pay raise for teachers to a three-year commitment to raise salaries by about 20 percent, assuming revenues stay flush.

#REDforED leaders have been skeptical that those funds are sufficiently stable as they are largely premised on continued robust economic growth. Teacher pay raises are only one of the demands put forward by Arizona Educators United, the organization leading the #REDforED movement. Other demands include competitive pay for education support staff (counselors, speech therapists, bus drivers, cafeteria workers, etc.), the restoration of education funding to 2008 levels, and suspending tax cuts until the state’s per-pupil funding reaches the national average, which would require a nearly $3,000 per-pupil increase.

However, if the debate solely focuses on education-related expenditures, we lose track of our ultimate goal, improving Arizona’s educational performance. How much funding does Arizona need to meet its educational goals?

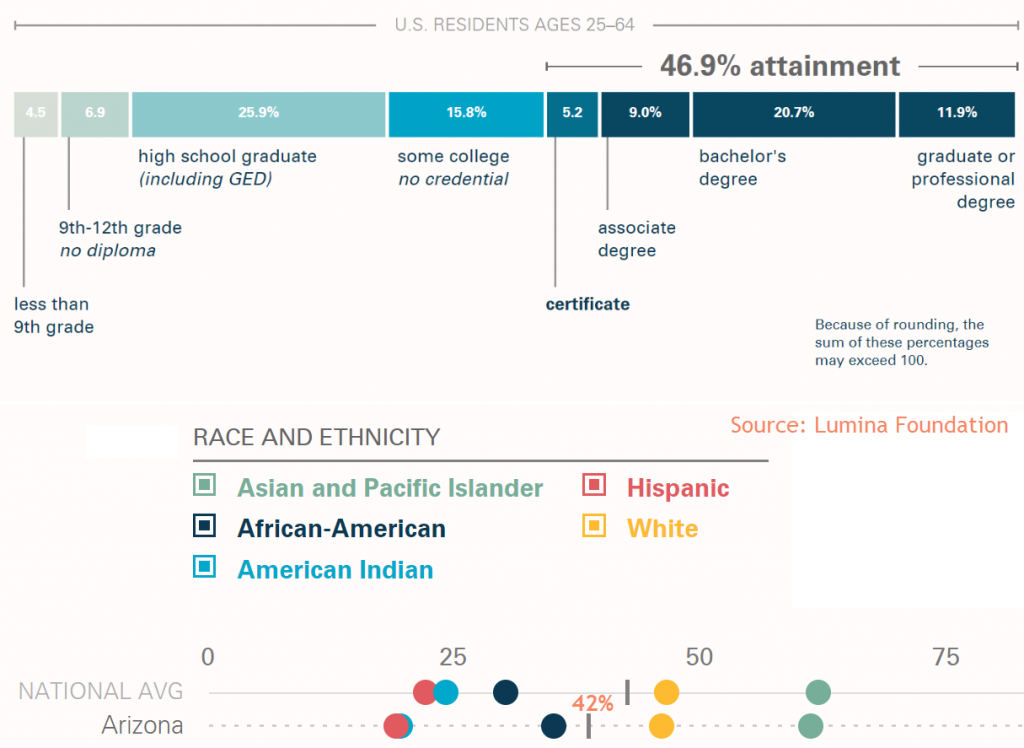

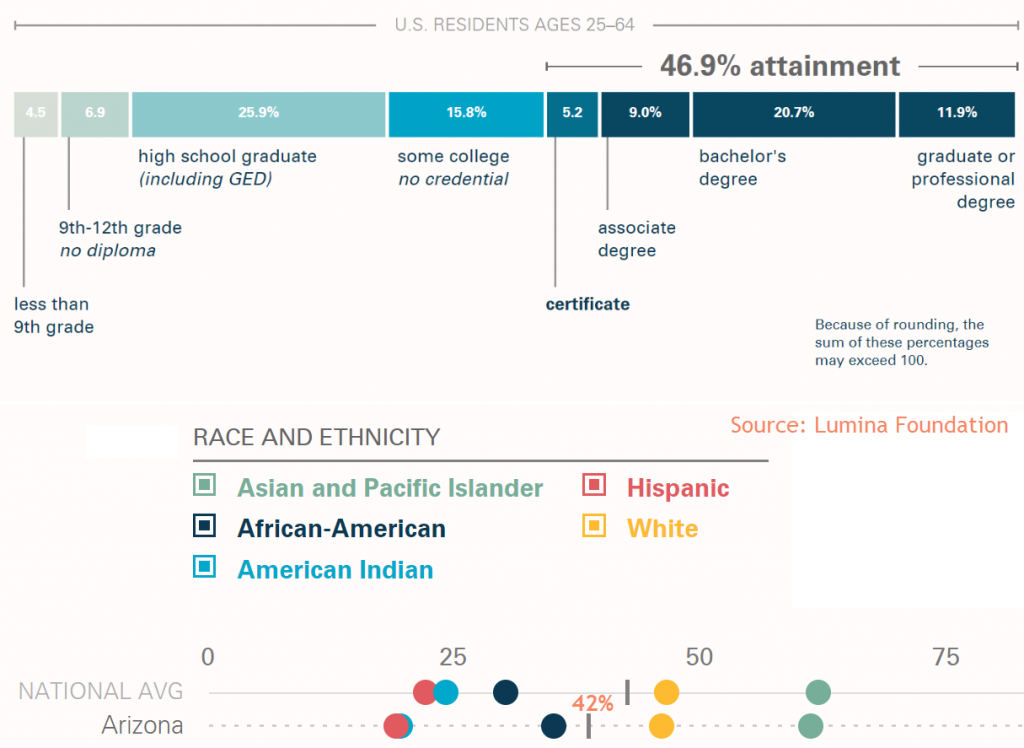

In September of 2017 Governor Ducey helped lead a coalition of community, business, philanthropic and education organizations in setting a goal that 60 percent of Arizona adults aged 25-64 attain a postsecondary degree or certificate by the year 2030, up from the current 42 percent. Reaching that goal is imperative, since the Governor and business leaders agree that within 5 years, nearly 70 percent of jobs will require education beyond high school. A key part of attaining that goal is “improving the K-12 pipeline.” The goals identified there were “increasing pre-kindergarten enrollment, third-grade reading levels, eight-grade math scores, and high-school graduation rates.”

For instance, Arizona’s high school graduation rate of 78 percent is in the bottom third of the country. California and Texas have similar portions of non-Hispanic white and Hispanic students yet do a better job graduating them. In recent years those states have improved, while Arizona has been stagnant.

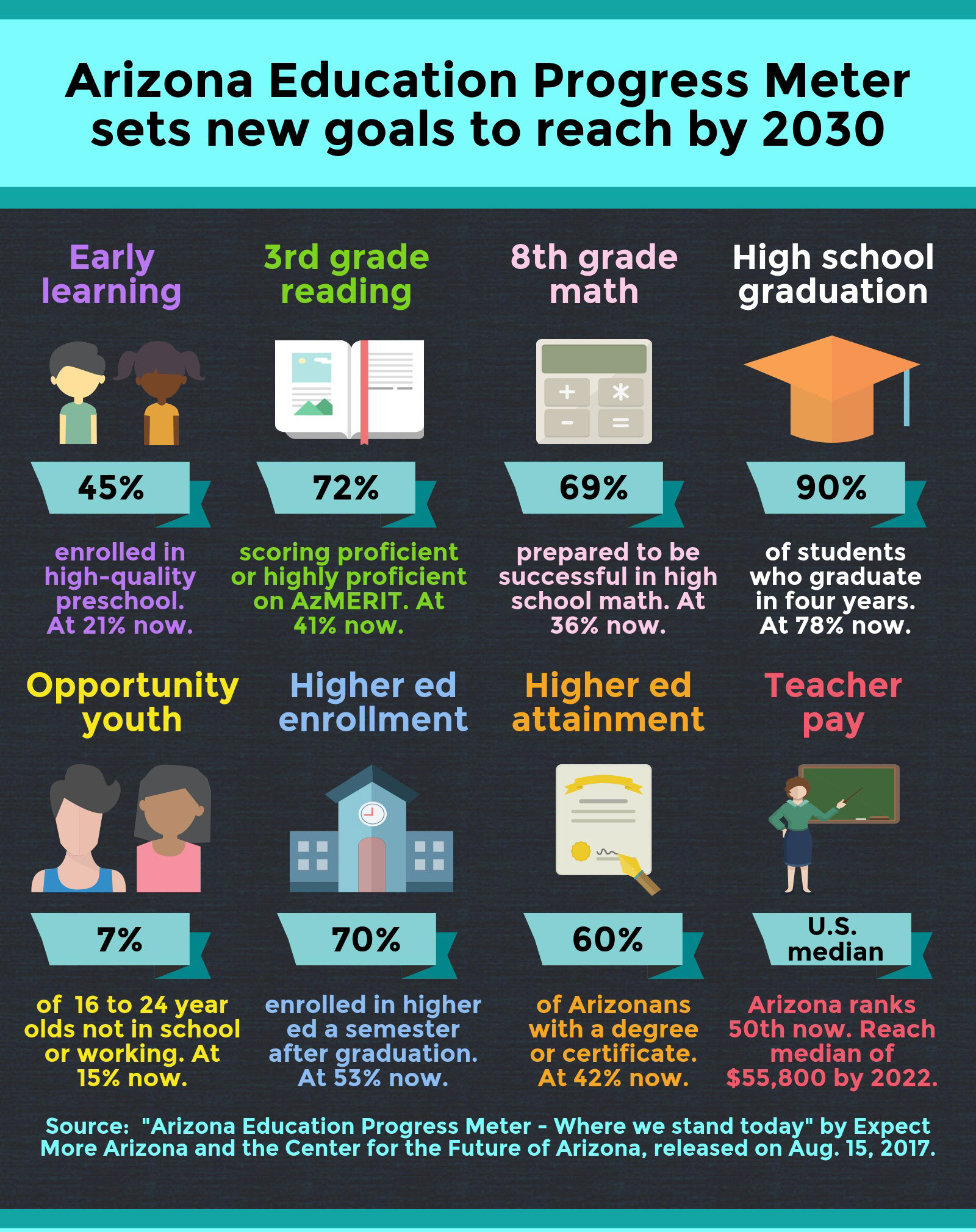

Two coalition partners—Expect More Arizona and The Center for the Future of Arizona— developed the Arizona Education Progress Meter that outlined a complementary set of goals to be reached by 2030.

Any discussion of educational investments ought to have these goals in mind. To reach these goals the state will need to identify new and dedicated funding sources—as there are not sufficient funds from economic growth or potential fund sweeps or savings from other governmental services to meet these needs. The state can start, however, with the $200 million in anticipated added revenue due to recently enacted federal tax reform including limits to deductions that will boost state revenue as estimated by the state’s department of revenue. Beyond that initial funding, the state will need to consider some combination of boosting the state income tax, examining potential services for taxation, increasing the state-education sales tax, removing some of the recently enacted corporate tax cuts, possibly reinstating a statewide property tax, and reviewing current state tax credits.

SUMMARY OF GCI RECOMMENDATIONS

The Grand Canyon Institute (GCI) has identified the following necessary education investments to reach the 2030 goals as well as correct K-12 capital deficiencies.

- Early Childhood Education—To meet the needs of children under the poverty line so they can be successful in school: $200 million.

- Teacher Salaries—To provide a $10,000 flat raise to Arizona’s teachers: $686 million. This will also improve student achievement by reducing the teacher shortage and enhancing recruitment and retention of teachers. A flat raise achieves these results better than a percentage increase.

- Added Interventions—To elevate student performance to achieve goals for third grade reaching, eighth grade math and high school graduation: $250 million

- Refilling Prior State Investments: $991 million[1]

- Soft Capital and Capital Overlay now known as District Additional Assistance: $352 million

- All-day Kindergarten: $265 million

- New School Construction: $284 million

- Building Renewal Funds: $90 million

Total Annual Investment: $2.1 billion

[1] These are funds that were cut from 2008 onwards during the Great Recession.

EDUCATIONAL INVESTMENTS TO REACH ARIZONA’S GOALS

1. Early Childhood Learning Goal: 45% of children are enrolled in a high-quality pre-school. (GCI recommends that this goal be further refined to include a supplementary goal that 100% of children in families below the federal poverty line receive home visits in the early years and then high-quality Pre-K).

Recommendation #1: Phase in $200 million in birth to five investments to better meet the needs of at-risk children in poverty.

Consider Antecedents. A growing body of evidence suggests that the first two to three years of a child’s development are critical and home-based targeted programs aimed at improving parenting have high returns. Since the end goal is high school graduation or more, this antecedent is important. Researchers have found that children born into low-income families are exposed to 30 million fewer words by age 3 than children living in higher income families. Stanford University psychologists found intellectual processing gaps by 18 months.

Consider Antecedents. A growing body of evidence suggests that the first two to three years of a child’s development are critical and home-based targeted programs aimed at improving parenting have high returns. Since the end goal is high school graduation or more, this antecedent is important. Researchers have found that children born into low-income families are exposed to 30 million fewer words by age 3 than children living in higher income families. Stanford University psychologists found intellectual processing gaps by 18 months.

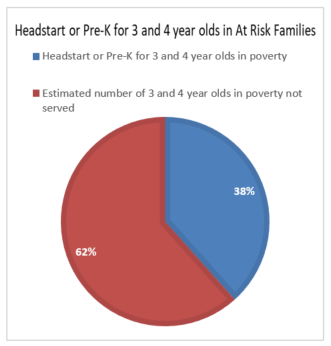

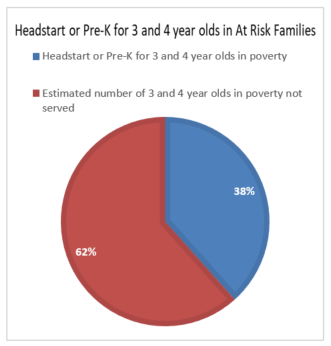

In addition, Arizona needs to make significant progress in its Pre-K preparation for 3 and 4 year-olds. The National Institute for Early Education Research gives Arizona middling marks. Current funding comes from First Things First, a citizen’s initiative that funds quality early childhood development and health programs for kids birth to age 5, before kindergarten. The program is a good down payment but not sufficient to meet what Arizona needs. The key is targeted program expansion.

In addition, Arizona needs to make significant progress in its Pre-K preparation for 3 and 4 year-olds. The National Institute for Early Education Research gives Arizona middling marks. Current funding comes from First Things First, a citizen’s initiative that funds quality early childhood development and health programs for kids birth to age 5, before kindergarten. The program is a good down payment but not sufficient to meet what Arizona needs. The key is targeted program expansion.

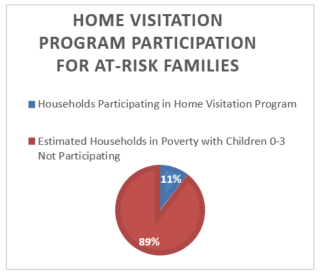

The federal Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) Program has been funding and evaluating pilot programs to establish evidence-based success. The programs target high-risk families most likely to benefit from visitation by trained professionals who work with parent(s) or caregivers to assist in pre-natal care to improve childrearing techniques and strategies. An added benefit could be reducing the number of children who might otherwise end up in foster care.

The federal Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) Program has been funding and evaluating pilot programs to establish evidence-based success. The programs target high-risk families most likely to benefit from visitation by trained professionals who work with parent(s) or caregivers to assist in pre-natal care to improve childrearing techniques and strategies. An added benefit could be reducing the number of children who might otherwise end up in foster care.

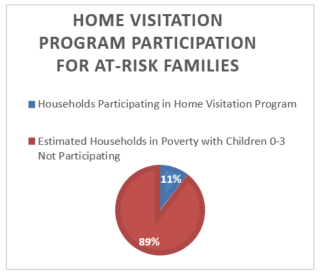

The First Things First 2017 annual report indicates that about 6,000 out of 55,000 households below the poverty line are currently receiving home visitation services for children age 0 to 3. The cost of these services depends on the length and intensity of the program. The annual cost can range from $2,500 to $5,500 per family based on estimates from Minnesota and Washington state. Using the lower end and assuming one year of full services that then taper over the next two years, meeting the needs of all households in Arizona would be about $80 million.

Arizona currently spends about $3,600 per child for Pre-K programs through First Things First serving 5,300 targeted children. Expanding that offering to reach all 3 and 4 year olds in families under the poverty line would cost about $115 million.

Collectively, the low-end cost of meeting the needs of at risk children under the poverty line from birth to five would cost the state an additional $200 million. These investments are critical in helping provide equality of opportunity and enable Arizona to reach subsequent goals in student achievement, including the 90 percent high school graduation rate.

2. Teacher Pay Goal: Achieve national median salary by 2022 and improve Academic Achievement

Recommendation #2: Flat pay raise of $10,000 for all full-time teachers.

Added Cost: $686 million

The Arizona Auditor General reports for fiscal years 2016 and 2017 indicate that if teacher pay had merely kept up with inflation then staying even with 2004 levels would put the average teacher pay at $51,300. Instead, despite raises from Prop. 123, average district teacher pay is $48,372, almost 6 percent less—even though average teaching experience has not changed. The national average teacher pay is about $59,000. The consequence is teachers leave the profession and vacancies become endemic.

Improving teacher pay by $10,000 makes sense. GCI recommends a flat increase to maximize gains to student achievement.

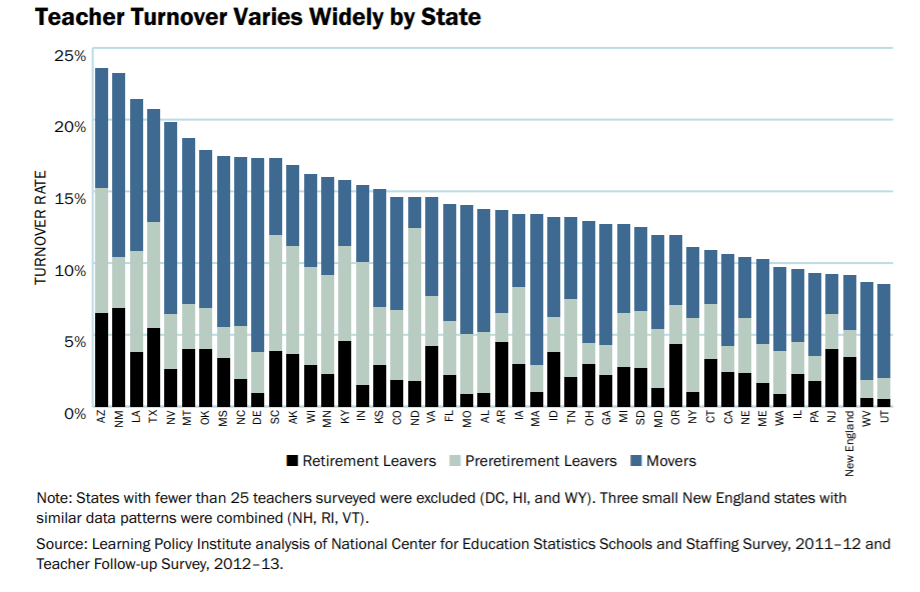

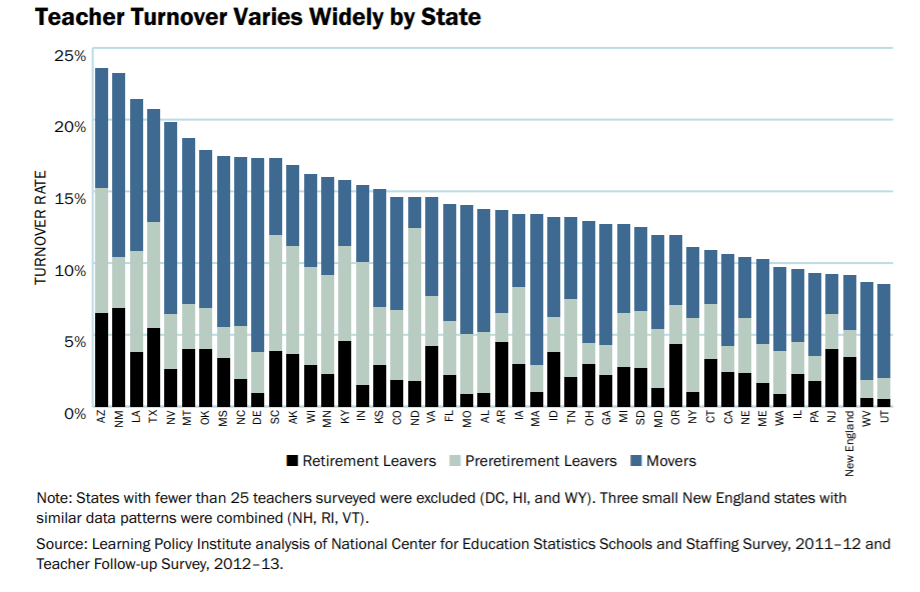

Arizona may lead the nation in teacher shortages. Data from 2011-2012 to 2012-2013 compiled by the Learning Policy Institute at Stanford University using national teacher survey data found Arizona had the worst teacher turnover in the country. It parcels results into those who retire, those who leave the profession or the state before retirement, and those who move between schools. Since then the situation has likely worsened. Their turnover report also indicated that Arizona was also last in comparative salaries with teachers only earning 62 percent of what professionals earn with the same level of education, age, and hours worked.

The May 2017 Morrison Institute report Finding and Keeping Educators for Arizona’s Classrooms noted:

More than one-quarter of the 8,344 openings for teaching jobs in Arizona for the 2016-17 school year were vacant as of Nov. 28, 2016. These vacancies were often filled by long-term substitutes or by having existing teachers teach extra classes. Another 27 percent of the openings were filled by those who did not meet the standard teacher requirements. This includes teachers whose certification is pending, and those with intern or emergency certificates. (p. 8)

The quality teacher shortage continues to grow. A December 2017 report from the Arizona School Personnel Administrators Association noted that with regard to teacher vacancies for this current school-year, 23 percent were still vacant and 39 percent were being filled by “individuals not meeting standard teaching requirements.” In addition, nearly 1,000 teachers had abandoned or resigned their position in the first four months of the school year. These results clearly indicate that salary levels are inadequate in Arizona and must be increased.

Emergency replacement teachers with less experience and training are less effective on average than other teachers, ultimately impacting student achievement. Most of those leaving the profession do so early in their careers. The Morrison Institute study found 42 percent of public district school teachers and 52 percent of charter school teachers have left the profession or the state by the time they start their fourth year teaching.

Senior Policy Analyst Dan Hunting of the Morrison Institute found 11.8 percent of all teachers left the profession from 2014 to 2015. This is similar to Oklahoma’s 11.1 percent annual rate from 2006 to 2014 as found by economist Mark Hendricks. By 2014 Oklahoma’s rate had risen, such that it was likely similar to Arizona’s. By contrast, Texas, which pays its teachers about $10,000 more when adjusted for the cost of living had a much lower rate of 8.4 percent.

Attrition rates are not evenly spread out across districts. Districts with higher portions of lower income students and in less desirable areas have higher rates of teacher attrition from their districts or the profession.

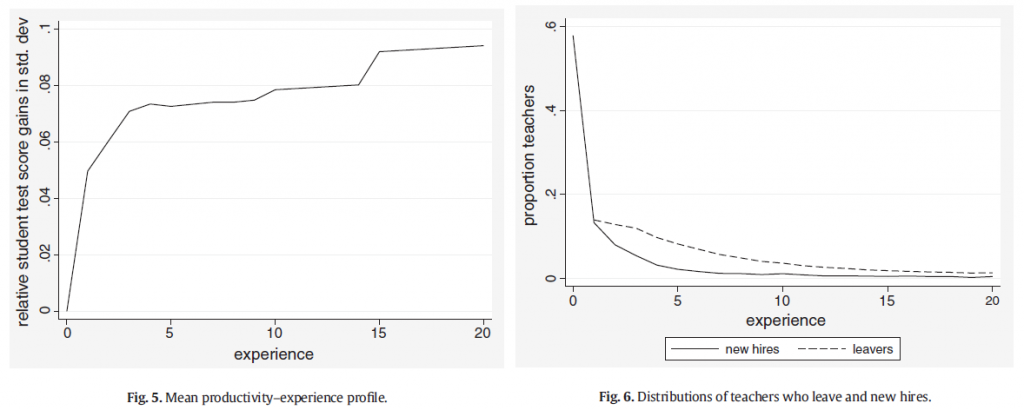

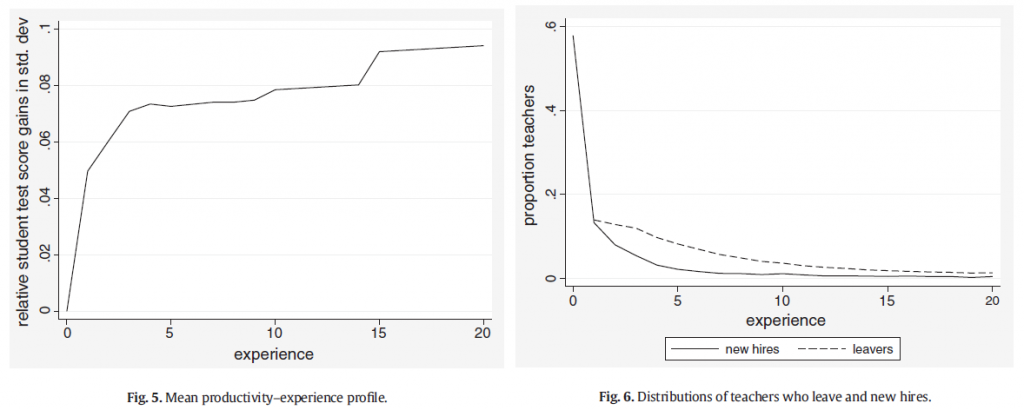

Teachers improve the most in their teaching during the first four years of their career, after which gains are more modest. This is shown in Figure 5 reproduced from Mark Hendricks’ 2014 article in the Journal of Public Economics based on taking mean results across the literature, which measures value-added for teachers through standardized test scores.

When teachers leave the profession, even though they may leave after only a few years, they are invariably replaced by teachers with less experience who will on average be less effective as shown in Figure 6 from the same article.

Research demonstrates that improving teacher pay will improve academic outcomes. A 2000 study of teacher salaries from 1960-1990 found a 10 percent increase in teacher pay relative to other occupations improved the high school graduation rate by 3 to 4 percent. Or otherwise stated, Arizona’s current substandard pay levels are lowering high school graduation rates. A 20 percent pay raise for teachers could make large gains toward the goal of a 90 percent high school graduation rate by 2030.

The detrimental impacts of funding cuts from the Great Recession on high school graduation rates has also been documented by Jackson, Wigger and Xiong of Northwestern University. While Lafortune, Rothstein, and Whitmore Schanzenbach found evidence that spending increases focused on low income students lead to clear improvements in scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

However, pay rates for teachers do not reflect well their productivity-experience profile, meaning teachers don’t see rapid gains in pay early in their careers which can lead to a widening gap between teaching and alternative career options. The ideal teacher pay scale would have a concave shape to better reflect this early gain in productivity.

A pay raise that more significantly rewards teachers with less experience will have a stronger impact on recruitment and retention and improving student achievement. Consequently, GCI recommends a flat rather than percentage-based pay raise. This approach would proportionally reward teachers with less experience the most, thereby having the greatest benefit in terms of student achievement.

The value of improved learning translates into lifetime gains for students. Chetty, Friedman and Rockoff in Measuring the Impacts of Teachers II; Teacher Value-Added and Student Outcomes in Adulthood from American Economic Review in 2014 estimate that if the lowest five percent of performing teachers were replaced by average performing teachers, the students in those classrooms would experience a net present value increase in lifetime earnings of $185,000. Adjusting to 2018 dollars (2011 dollars reported in the study), that value would be $205,000. This illustration assumes 19 of 20 (95 percent) classrooms are not changed. Under that assumption the average annual gain per classroom in student lifetime earnings is $10,250. This represents the total gain in earnings across all students in the classroom. This estimate seems like a reasonable and modest approximation given that about 10 percent of teaching positions are either vacant or being filled by someone who does not meet standard teaching requirements.

Cost: $686 million. This assumes 60,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) teachers and recognizes that $34 million has already been budgeted for a 1% salary increase. Assuming that amount was redirected as part of a flat pay increase of $10,000 per FTE teacher (prorated for those part-time). This amount is about $100 million more than the Governor has put forward so far. The cost includes an added 20 percent to cover employee-related expenses, such as FICA and ASRS contributions primarily.

- Added Investments for Student Achievement

Recommendation #3: Add $250 million of additional education funding for intervention programs already shown to improve student performance.

- Third Grade Reading Goal: 72% of students score proficient or highly proficient on AZMerit tests, up from 41% now

- Eighth Grade Math Goal: 69% of students are prepared to be successful in high school math, 36% now

- High School Graduation Goal: 90% of students graduate from high school, up from 78% now

Providing early childhood education and improved teacher pay would help reach the above goals, but additional interventions would be necessary. Precisely quantifying those interventions is beyond the scope of this analysis. However, assuming one FTE interventionist was needed per 400 students at a cost of $70,000 including employee-related expenses (health insurance, retirement, employer-paid FICA taxes), then for about 1.1 million students, the cost of the added interventionists would be approximately $200 million. How that position might be used or allocated could vary from tutoring, school social workers, and reading or math enrichment teachers. This estimate is likely on the low-end of what interventions might be needed.

Staying competitive for interventionists will also require raising the pay levels of those currently employed in that capacity. In addition, teacher aides have high turnover rates and while many barely make more than minimum wage. Consequently, an added $50 million is provided for salary adjustments. This may also be a low-end estimate.

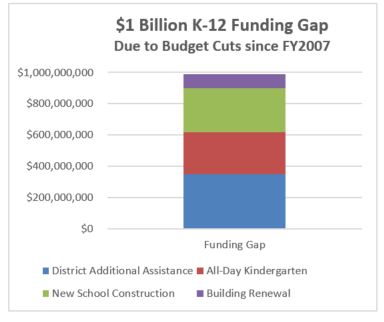

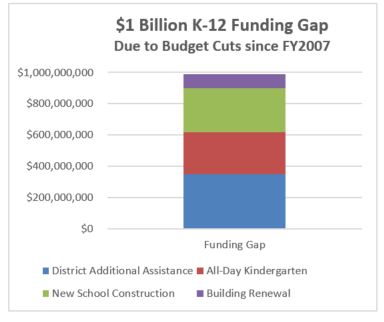

- Refilling Capital Investment Holes and Full-Day Kindergarten: $ 990 million

FY2007 was a peak year for recent education funding, so is a benchmark to measure the degree to which current appropriations match it when adjusted for the number of students and inflation. This aspect focuses on those elements excluded from Prop. 123. Areas outside the inflation adjusted base level include money for computers and textbooks formerly known as Soft Capital and now called District Additional Assistance. Following the Roosevelt v. Bishop Case, the state also took on more responsibility for school repairs and construction. Finally, Governor Napolitano was successful in securing funding for all-day Kindergarten. That was rescinded when stimulus money ran out, despite a temporary sales tax, and the state returned to funding only a half-day of Kindergarten. The District Additional Assistance shortfall is noted as a suspended statutory formula in the 2018 JLBC Tax Booklet. All-day Kindergarten cost is estimated by taking the amount spent in FY2010, the last year it was funded, and adjusting it for the change in base funding as well the

growth in students. Building Renewal and New School construction amounts are based on the FY2007 appropriation and is adjusted for the growth in students as well as the change in the implicit GDP price deflator (inflation). This yields about a $1 billion shortfall.

- Soft Capital and Capital Overlay now known as District Additional Assistance: $352 million

- All-Day Kindergarten: $265 million

- New School Construction: $284 million[1]

- Building Renewal Funds: $90 million

Total $991 million

Conclusion

All Arizonans want to see our children be successful at school. The Arizona Education Progress Meter provides specific goals to guide students along that pathway. Understanding what resources are required to achieve each of those goals is fundamental. The Grand Canyon Institute’s policy analysis provides policy makers and education leaders with the funding requirements to guide a discussion regarding the resources the state realistically needs to commit to K-12 education. This information should be considered in the context of the demands put forward by the #REDforED movement. Teacher pay raises are a part of a larger funding scenario that will ensure the success of Arizona’s K-12 students.

Dave Wells holds a doctorate in Political Economy and Public Policy and is the Research Director for the Grand Canyon Institute. He can be reached at DWells@azgci.org or contact the Grand Canyon Institute at (602) 595-1025, Ext. 2.

The Grand Canyon Institute, a 501(c) 3 nonprofit organization, founded in 2011, is a centrist think tank led by a bipartisan group of former state lawmakers, economists, community leaders and academicians. The Grand Canyon Institute serves as an independent voice reflecting a pragmatic approach to addressing economic, fiscal, budgetary and taxation issues confronting Arizona.

Grand Canyon Institute

P.O. Box 1008

Phoenix, Arizona 85001-1008

GrandCanyonInstitute.org

[1] This amount can be reduced in early years by bonding for school construction, although bonding requires paying back debt.

Budget

Budget