Budget

Budget

Why Arizona’s Regulatory Moratorium is Unnecessary

April 20, 2014This GCI report examines the number of regulations approved for executive agencies, boards and commissions during a twelve year period, 2000-2012, within the context of the state’s larger economy. Environmental regulations are analyzed particularly for their identified costs. Consistent with the literature, approved regulations appear to have little, if any, effect on aggregate employment and jobs; many of the approved regulations were requested by business. Other rules focused on streamlining processes, reducing the time required to secure permits, and adding flexibility to regulatory programs. Moreover, the final four years of the study include the results of the Brewer Administration’s moratorium on agencies promulgating regulations, where very few regulations were approved, yet Arizona experienced the most costly environmental regulation of the study period. The policy brief concludes that regulations can be compatible with employment growth, and there is no economic reason to impose a moratorium. The regulatory state is both critically necessary and imperfect. The aim of our discourse should be neither to demonize nor discredit, but improve it. The report identifies three solutions to improve Arizona’s regulatory practice that will help ensure sensible, cost-sensitive, transparent regulation, a far better public policy for the state than moratorium.

Policy Improvement #1: End the moratorium on regulations. It discourages state agencies from updating current rules that mirror today’s and tomorrow’s requirements for protecting people, places and products.

Policy Improvement #2: Overall, the economic assessments of environmental regulations are uneven and could be improved by increasing efforts to secure specific data from both affected businesses on the cost side and affected communities on the benefits side.

Policy Improvement #3: Shining the light on agency regulatory requirements is crucial for citizen understanding. Legislative exemptions from the process should be directed at immediate regulatory needs. Efforts to engage citizens need to be enhanced.

Policy Report

April 21, 2014 8 a.m. MST

Why Arizona’s Regulatory Moratorium is Unnecessary

Karen L. Smith, Ph.D.

Fellow, Grand Canyon Institute

Summary

Governor Brewer and the Arizona Legislature have stated repeatedly that “regulations are job-killers” and “obstacles to the private sector creating jobs,” and through executive and legislative moratoriums have essentially stopped all agencies’ efforts to craft the necessary regulatory approaches needed to implement the programs the Legislature has directed them to do. This is not productive policy and may cause harm. This GCI report examines the number of regulations approved for executive agencies, boards and commissions during a twelve year period, 2000-2012, within the context of the state’s larger economy. Environmental regulations are analyzed particularly for their identified costs. Consistent with the literature, approved regulations appear to have little, if any, effect on aggregate employment and jobs; many of the approved regulations were requested by business. Other rules focused on streamlining processes, reducing the time required to secure permits, and adding flexibility to regulatory programs. Moreover, the final four years of the study include the results of the Brewer Administration’s moratorium on agencies promulgating regulations, where very few regulations were approved, yet Arizona experienced the most costly environmental regulation of the study period. The policy brief concludes that regulations can be compatible with employment growth, and there is no economic reason to impose a moratorium. The regulatory state is both critically necessary and imperfect. The aim of our discourse should be neither to demonize nor discredit, but improve it. The report identifies three solutions to improve Arizona’s regulatory practice that will help ensure sensible, cost-sensitive, transparent regulation, a far better public policy for the state than moratorium.

Policy Improvement #1: End the moratorium on regulations. It discourages state agencies from updating current rules that mirror today’s and tomorrow’s requirements for protecting people, places and products.

Policy Improvement #2: Overall, the economic assessments of environmental regulations are uneven and could be improved by increasing efforts to secure specific data from both affected businesses on the cost side and affected communities on the benefits side.

Policy Improvement #3: Shining the light on agency regulatory requirements is crucial for citizen understanding. Legislative exemptions from the process should be directed at immediate regulatory needs. Efforts to engage citizens need to be enhanced.

Introduction

When Jan Brewer became governor in January 2009 upon Janet Napolitano’s resignation to become U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security, one of her first acts was to declare a moratorium on new regulations within Arizona. Governor Brewer, like many other conservative politicians, believes that regulations generally threaten economic vitality and are “job killers.” While providing some exceptions for significant threats to public health and safety, the Governor’s, and later the Legislature’s, moratorium on agency rulemaking has stopped most new rulemaking by Arizona agencies. In speeches to the Arizona Farm Bureau and the State of Small Business Breakfast, as just two examples of comments to business groups since she became governor, Governor Brewer has consistently characterized government regulation as an “obstacle”, as an impediment to American fundamentals of freedom and private property, and committed to keep regulations “lean” so that the private sector can create jobs and the government get out of the way.

Is she right? Have regulations “killed jobs” within Arizona? While it’s a popular ideological presumption, evidence should drive regulatory decisions. This GCI policy brief looks at Arizona regulations enacted over a twelve year period, from 2000 through 2012, with two Republican and one Democratic governor, with specific analysis of environmental regulations. First, the policy brief explains the rationale for regulation and how the Arizona regulatory scheme is constructed. Next it looks at regulations for executive agencies, boards and commissions approved during the twelve year time period to see where rules are occurring. Environmental regulations often receive the brunt of the anti-regulatory rhetoric, and those regulations are specifically analyzed for their cost impact and how the regulatory process might be improved. Finally, the paper concludes with thoughts on the effectiveness of regulatory moratoriums and what actions Arizona needs to take to have an effective and efficient regulatory environment.

Why Regulation?

In a perfect world, all markets would consist of large numbers of sellers of a product, providing competitive prices, and consumers would be fully informed of the product’s benefits and risks. There would be no positive or negative effects impacting others that would come from either making or consuming the product (externalities), as all effects would be known and, therefore, internalized by buyers and sellers; there would be no need for outside intervention. We do not live in a perfect world, however, but in one shaped by market failure, where too much pollution is produced, consumer information is imperfect, and the market itself is inefficient. Even Adam Smith, the most cited proponent of the free market, acknowledged the possibilities of collusion to raise prices and to conspire against the public among businessmen in the same trade. Recent experiences of ENRON manipulating energy prices that cost Californians billions of dollars, the British Petroleum oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico that ruined Gulf Coast states’ shore environment and economy, and the financial industry collapse that caused the Great Recession of 2008 starkly remind us of the consequences of market failure. Its negative effects litter the landscape, in air and water pollution, harmful products and drugs, and tainted food, as examples. In the imperfect world in which we live, individuals sometimes need the visible hand of their government to balance these failures.

More than 140 years ago, the American people demanded government intervention to correct this failure of free markets when railroads conspired among themselves to set discriminatory prices to move goods, favoring certain commodities and sellers over others. It was, in short, unfair, and in the rough and tumble laissez-faire economic environment of 19th century America, more common than not. Yet popular dissatisfaction with railroad and others’ monopoly power caused certain states to object. The State of Illinois first decided to regulate business, in this case rates for grain storage, and end discriminatory pricing through creation of a public commission. Litigation ensued and the resulting U.S. Supreme Court decision, Munn v. Illinois (1877), laid out the foundational principle that the public did have an interest in the way private business was conducted. The State, the Court believed, has a right through its police power to regulate businesses with a public interest, to correct the market’s deficiencies and flaws. Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act creating the Interstate Commerce Commission (1887) and the regulatory state was born. Since then, Congress has created a myriad of independent and executive branch agencies and given them general authority to correct market deficiencies.

The recognition that private actions within the marketplace can create serious public consequences frames regulation in America, whether it is economic or social in nature. Economic regulation governs conditions under which firms may enter and exit the market, competitive practices, the size of economic units or the prices firms can charge, typically focused on a single sector of the economy, such as banking/finance. Social regulation is designed to force corporations to accept greater responsibility for the safety and health of workers and consumers and for the negative effects of the production process on the environment. It also addresses issues such as equal opportunity in employment. Social regulations apply across all sectors of the economy and have been the most dominant form of regulation since the 1970s as civil rights and quality of life issues rose in importance. From disclosure and publicity, containing monopoly or oligopoly, creating economic harmony among industries, promotion or advocacy to further the public interest, protecting the environment, and consumer protection, the regulatory state has many purposes and is deeply entrenched in our daily lives.

Regulation and the States

When the U.S. Supreme Court decided Munn v. Illinois (1877), the concept of government intervention to correct market abuses arose in the states, not the federal government. The states, then as now, are often laboratories of innovation, closer to problems affecting the citizens in their states and typically first to develop new methods of governance, such as regulation to impose order over perceived economic chaos. The problem, however, then as now, lies in the nature of commerce. It is mostly interstate in character, today often more global than national. As an example, as each state developed its own regulatory scheme to control railroad rates, the ability to do business across more than one state became uncertain, too complex and patchwork, with myriad rules and requirements. Business sought a single unified scheme in federal regulation instead. The Interstate Commerce Commission (1887) was one of the first instances where Congress and the Court applied the Constitution’s commerce clause to justify federal primacy over regulating an industry that crossed state lines. Since then, the framework for regulatory intervention in the market has been primarily one based on federal rules, with the states maintaining regulatory control over state-only programs, such as land use, water allocation schemes and public utilities, such as electric and gas companies providing retail service.

Beginning in the 1970s, the federal government began a movement to return management of certain national regulatory programs to the states, such as the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) clean air and clean water programs, although with the mandate to enforce federal minimum standards so as to maintain a level playing field across the country relative to environmental protection. States, in their competitive eagerness to secure industry and jobs, cannot waive the requirement to implement environmental regulations in order to secure business to their state thereby creating the proverbial “race to the bottom”. However, they have the ability to make these federal requirements more stringent within their state, achieving greater protection should they choose to do so; a federal “floor”, but no ceiling. In Arizona, the Legislature has provided that no state regulation shall be more stringent than the federal program, ensuring the federal “floor” is Arizona’s “ceiling.” Returning operational management of certain federal regulatory programs to the state allows for greater flexibility and creativity in regulatory implementation, recognizing local conditions, and less “command and control” that is required from a centralized effort.

While most would agree that government regulation has an important role in correcting market failure and protecting citizens from pollution and unsafe food, drugs and other products, there remain significant concerns with the regulatory process itself. Critics decry a lack of political accountability of regulatory agencies; that they have been “captured” by the very industries that they regulate, working for the benefit of special interest groups and not the public and consumer interests they were designed to protect; that agencies have been created to deal with specific problems and therefore have potential for overlapping and inconsistent mandates that can result in duplication of efforts; that costs to comply are excessive, procedures are burdensome, and results of regulation inconsistent and inefficient. These perceived problems with the regulatory state have led both the federal government and the states on a path of reform.

The Arizona Regulatory Scheme

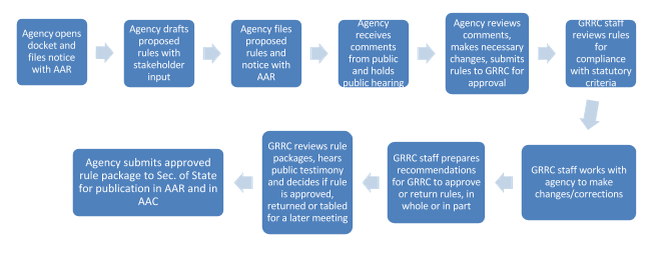

Before 1981, Arizona’s regulatory process mirrored problems most governments were having with the regulatory process generally – agencies, boards and commissions had grown over time to a large number, with little coordination among them, negligible political accountability and limited consistency in the rulemaking process. Some economic regulations, such as those limiting exit and entry in airlines, trucking and interstate banking, were archaic, given the nature of the changing economy. These regulations were repealed at the national and state level, beginning in the late 1970s. In 1981, Democratic Governor Bruce Babbitt initiated a several decade process of regulatory reform in Arizona when he issued an Executive Order to create the Governor’s Regulatory Review Council (GRRC), a gubernatorial appointed body tasked with reviewing and approving all agency rules to ensure their clarity, understandability and that the benefits of the regulations justify their costs. Changes to the regulatory process included a plain language explanation of what the rule was about and why it was needed, the agency’s legal authority for implementing the regulation, as well as an economic impact analysis. It introduced specific elements of public notice, comment and participation in a public hearing to ensure all interested groups had knowledge of the rulemaking. With the creation of the GRRC, Governor Babbitt provided for outside review of agency rules so that no agency could implement a regulation without its approval, thereby eliminating any propensity for an agency to run amok with regulatory authority.

Babbitt’s regulatory reform agenda served as the foundation for later efforts to continue streamlining the regulatory process, through creation of a “Regulatory Bill of Rights,” institution of an agency requirement to issue permits and licenses in a timely manner or return the fees paid, and expansion of the required economic analysis to include an evaluation of impacts to small business and consumers. Administrative review of rules and regulations within the state is, therefore, very comprehensive. Proposed rules are reviewed for legality and form, for clarity and understanding, and their impact on the economy, small business and consumers. Substantial provisions exist for formal public participation in the rulemaking process through public notice, comment and public hearing, as well as informal opportunities through agency stakeholder meetings. If, after the rule has been finalized for 2 years, a person who believes the actual economic, small business or consumer impact significantly exceeded the agency’s estimates, they may file a written petition to the agency, which then must reevaluate the impact statement. Finally, every 5 years, the agency must perform a retrospective analysis of its rules to determine whether any rule should be amended or repealed.

Most state agencies are subject to Legislative Review through a “sunset” process that presumes an agency will expire unless the case can be made for its continuation, typically every 10 years, although the Legislature has set shorter continuation time periods for certain agencies before another sunset hearing is required before the Legislative Joint Committee of Reference. By establishing an “orderly schedule for the termination of existing state agencies, the Legislature will be in a better position to evaluate the need for the continued existence of current and future agencies, departments, boards, commissions institutions, and programs of this state,” including agency powers and duties. Tension between the Executive and Legislative branches of government over where authority for the regulatory process should reside has continued since 1981 when Governor Babbitt and Republican House Majority Leader Burton Barr tussled over this issue. The primary arena for regulatory approval remains with GRRC and the Executive branch, but the Legislature has, in recent years, created legislative committees and commissions to provide alternative avenues for regulatory review as well as including specific regulatory requirements within session law.

Arizona Rulemaking Process

Arizona Approved Regulations, 2000-2012

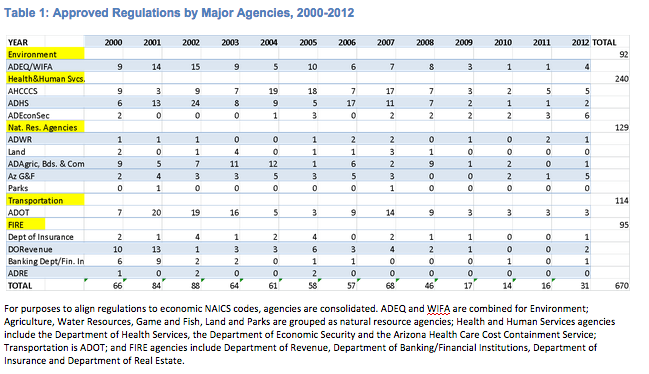

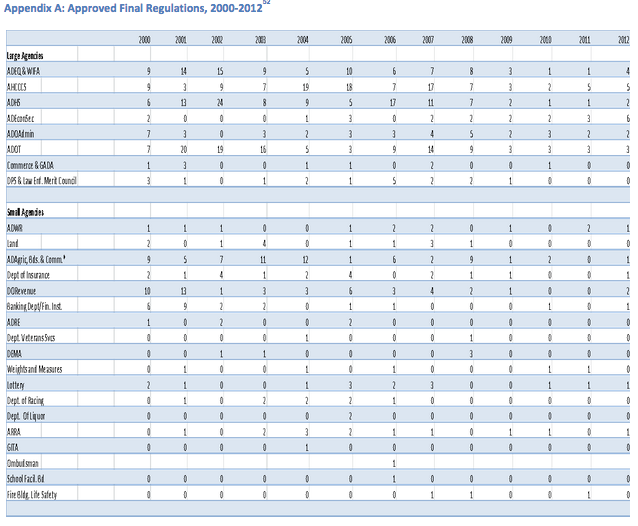

The twelve year period spanning the first part of the 21st century provides a useful timeframe to analyze Arizona regulations since it experienced two Republican governors, Jane Dee Hull (1997-2002) and Jan Brewer (2009-present), and one Democratic governor, Janet Napolitano (2003-2008) , offering an opportunity to see how political party might affect the scale and scope of regulations; the Arizona Legislature was controlled by the Republican Party throughout the study period. There were 1,117 final rules by state agencies, boards and commissions, and licensure agencies approved through the GRRC process from 2000-2012. Appendix A lists all approved rules during this time period, by year, from executive branch agencies, independent agencies with gubernatorial approved commissions or boards, and so-called “90/10” agencies, which are typically small professional/occupational licensure agencies whose mission is to prescribe the rules by which those licensed must operate. Slightly less than 20% of the approved rules (200) are for the professional/occupational licensure agencies, prescribing standards and methods for groups as diverse as barbers and radiologic technicians, pharmacists to funeral directors; failure to obtain a license is an enforcement issue, which allows the profession/occupation to limit /control who might participate. Gubernatorial Commissions and Agencies had 163 of the final rules, about 14% of the total. These agencies are managed by an appointed board or commission, varying from the larger Game and Fish, Industrial Commission and State Parks, to the Arizona State Retirement Board and Commission on the Arts as examples. Smaller state agencies such as the Arizona Department of Water Resources, the Land Department, and Agriculture promulgated 242 rules or about 22% of the total. About half of the total rules, 512 or about 46% were rules needed by the large agencies like the Arizona Department of Health Services, the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, the Arizona Department of Economic Security, the Arizona Department of Transportation and the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality. Arizona’s regulatory approvals for major rules appear to follow a typical regulatory distribution, with health and human services, transportation and environment as lead programs, if federal rulemaking is any guide.

Simply counting regulations has deficiencies, however, in evaluating regulatory impact. Agencies aren’t consistent in drafting rules; some may submit 3 separate rules, others a single rule with 3 parts. Rules proposed vary significantly in importance, quality and economic impacts. And agencies vary significantly as to mission, function and size. Additionally, some state approved regulations are simply mandatory incorporation of federal requirements for federal programs now managed by states, such as Medicaid and Safe Drinking Water and Clean Water and Air rules. Still, the number of regulations approved provides insight into agency activity, their level of effort to implement their programs and the scope of Arizona’s regulatory focus.

Of the three governors, Governor Napolitano served as the state’s chief executive during half of the study period (six years, 2003-2008) and not surprisingly, slightly more than half of the total approved rules occurred during her administration (626 rules, about 56%). What might be more surprising is that more than 30% of all approved rules occurred during the final three years of Governor Hull’s administration (349 rules, 31%), one-fourth of the study period, suggesting political party alone may not be the determining factor in advancing regulatory activity in Arizona, as both the Executive and Legislative branches were controlled by Republicans. Governor Brewer’s administration slight regulatory record (138 rules or 12%) is not surprising, given her political views on regulation generally. In this instance, both the Executive and Legislature are controlled by very conservative members of the Republican Party that reflect a more ideological approach to governing than the Republican Party in office during Governor Hull’s term. Yet some caution is in order when evaluating Governor Brewer’s administration “regulatory lite” record as several rules were finalized as exempt from the more transparent GRRC process with some of the most substantial costs occurring in the array of rules devoted to increasing fees for agency activities. In this instance, significant costs occurred outside of a public process that invites citizen input and left decisions to small groups of business interests working with Governor’s staff and legislators in the state budget process.

Republican Hull’s administration promulgated more rules in significant areas of health and human services, natural resources, environment, transportation and the finance-insurance-real estate agencies, regulations crucial to implementing her signature programs like Kids Care and Growing Smarter. The state also pursued and received “primacy” or the ability to administer federal programs, securing new authority for Clean Water Act programs and reauthorization for programs that had lapsed, like the Hazardous Waste program, during Governor Hull’s Administration. Democrat Napolitano’s administration also promulgated important rules in the same major areas, but especially in the health and human services, environment, natural resource and transportation areas. Comparing the last three years of Governor Hull’s term with the last three years of Governor Napolitano’s shows little difference between the two administrations’ regulatory approvals; 349 rules for Governor Hull and 315 for Governor Napolitano. Republican Brewer’s administration has been focused primarily on the struggling economy and many of the approved rules in her four years in office have been for agency fee increases, as agency budgets have shrunk drastically as a result of state general fund deficiencies, and some, like ADEQ, have been told to become financially self-sufficient. Other rules were not surprisingly for human services agencies like the Department of Economic Security, focused on unemployment issues.

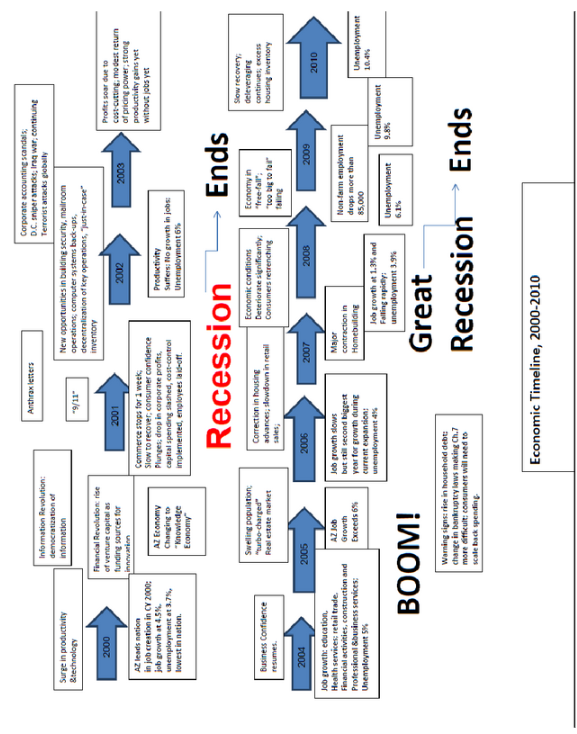

All three administrations governed during periods of economic recession; the Hull and Napolitano administrations also enjoyed a period of significant economic growth that so far has eluded the Brewer administration. All three administrations experienced the substantial reverberations of national and global change, especially stemming from terrorism, war, and corporate financial scandals. See Appendix B for a timeline of economic events, 2000-2010. It is against this back-drop of external events and administrative priorities that regulatory activity occurs; teasing out the singular impact of regulation from seismic events like terrorist attacks and war is nearly impossible. Analyzing regulations’ effects on employment is particularly difficult because it requires examining not only job gains and losses, but also the costs of job shifts, where a displaced worker due to regulatory change is transferred to another area of business. As University of Pennsylvania professor Cary Coglianese wrote recently, “. . . undoubtedly regulation does sometimes lead to some workers being laid off due to plant closures or slowdowns, but also it is true that workers are sometimes hired to install and run new technologies or processes needed to comply with new regulations . . . even if losses and gains sometimes cancel themselves out when tallying aggregate impacts, regulations can still create consequences with job shifts.” It is possible for any given regulation to have a positive or negative effect on jobs within an individual regulated sector just as it is possible for regulation overall to stimulate jobs just as it reduces them. This is not a theoretical task, but one that must be constructed, layer by layer. Several economic studies have done just that and most have concluded there is little effect of regulation on growth. New work completed within the past year continues to explore the nuanced relationship between regulation and jobs and concludes regulation has at most modest positive or negative effects on employment; the debate is one fueled more by political rhetoric than social science. At the state and local level, economic cost-benefit analysis of regulatory standards by government is often suboptimal. The purpose here is not to provide a detailed empirical analysis of Arizona regulation and jobs; that is a task for others. Instead, a picture of Arizona regulatory activity viewed against a backdrop of employment sectors allows us to see in the aggregate how the two align. To construct this picture, approved rules for the so-called “90/10” or professional licensure agencies and the small agencies and boards and commissions are removed from the analysis to illustrate the more significant impact the regulations of the medium to large agencies have both on the nature of the approved regulations and their relative impact to the basic Arizona economy.

Table 1: Approved Regulations by Major Agencies, 2000-2012

For purposes to align regulations to economic NAICS codes, agencies are consolidated. ADEQ and WIFA are combined for Environment; Agriculture, Water Resources, Game and Fish, Land and Parks are grouped as natural resource agencies; Health and Human Services agencies include the Department of Health Services, the Department of Economic Security and the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment Service; Transportation is ADOT; and FIRE agencies include Department of Revenue, Department of Banking/Financial Institutions, Department of Insurance and Department of Real Estate.

Viewing the Arizona regulatory landscape against a backdrop of employment sectors requires consolidating agencies to reflect the federal economic NAICS codes. Table 1 shows approved regulations by the major agencies, consolidated to align with federal economic NAICS codes. About 20% of all GRRC approved regulations were for health and human services; only 8% were for environmental programs. Note the activities of the Arizona Corporation Commission, a separate, elected, constitutionally created regulatory body that oversees the state’s public utilities and securities activities, are not subject to GRRC approval and are not included in this analysis, nor are the regulatory actions of the State Board of Education, again overseen by a separately elected state official, the Superintendent of Public Instruction.

Regulations and the Economy

Arizona’s economy has long been driven by population growth and its attendant benefits, but beginning around 2000, the economic structure of the state began to shift towards the so-called “Knowledge Economy”– driven by Information, Technology, Financial Innovation, and Productivity– leaving behind the traditional “4 Cs” of copper, cotton, citrus and climate as a historical artifact. Even so, the major nonagricultural employment sectors are services, including professional and business services, health care and social assistance, food services and drinking places, which have employed more than one-third of all Arizonans in non-farm employment. This reflects Arizona’s position as both a tourism draw and the growing importance of the biotechnology and health care sector within the state. Home building and its ancillary retail trade remain very important, buoyed by Arizona’s growing population; construction at its height of employment in 2006 employed about 9% of the non-farm workforce. Retail trade, state and local government, which is primarily state and local education, durable goods manufacturing, and finance and insurance complete Arizona’s major 21st century employment sectors.

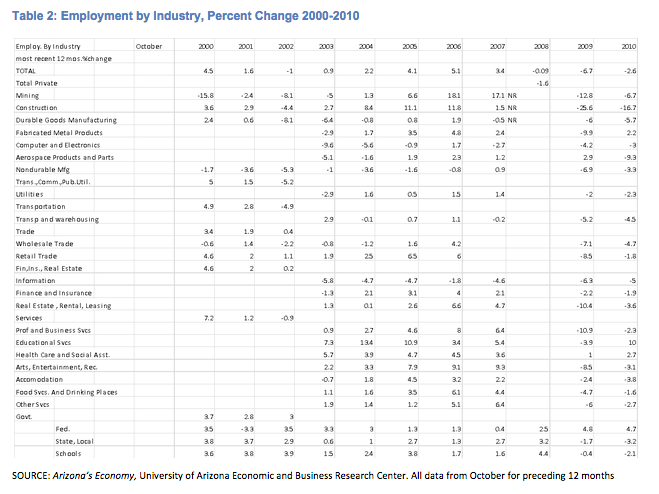

Arizona added 1.3 million people from 2000-2010 and state gross domestic product (GDP) grew from $161.8 billion to $249.8 billion, a decade of considerable growth for the state. A relatively mild economic recession that began following the events of September 11, 2001 caused a drop in state employment gains that had grown steadily since the start of the decade, yet job growth turns positive again in 2003 and grows slowly until 2005, when it jumps in number as the economy becomes “turbo-charged”, fueled by a housing boom enabled by new (and riskier) financial innovations, including sub-prime mortgage lending. Collapse of the financial services industry sparked the Great Recession that began in 2007 and ended officially in 2009, although many of its effects continue to plague the economy, including within Arizona. Table 2 highlights Arizona’s employment by industry, 2000-2010.

How then does a mainly services-driven growth economy fare in our regulatory story? Most of the approved regulations were promulgated by the Health and Human Services agencies; one of Arizona’s key employment growth areas was health care and social assistance. This is not to say regulations helped or hindered this growth, but merely reflects the active relationship between the two; it’s not surprising that a growing area of the public health and social assistance economy reflects growing areas of governance. Environmental regulations affect the mining, construction, utilities and transportation sectors especially, but also manufacturing. Here, the picture is less clear for a regulatory relationship and a more detailed regulation by sector analysis should occur. However, many specific studies on environmental regulation and jobs have failed to find significant negative employment effects, and our expectation is that is true for Arizona as well. What we might conclude from this cursory review of one of Arizona’s strongest growth decades is that the macroeconomic effects of recession, bubbles bursting, terrorist events and war altered employment growth more than any possible effect of regulation. At an aggregate level, the approved regulations from 2000-2010 occur within a decade of overall significant positive job growth and do not signal a burdensome effect. This observation is consistent with recent literature that suggests that federal regulations neither kill jobs nor stunt economic growth.

Table 2: Employment by Industry, Percent Change 2000-2010

SOURCE: Arizona’s Economy, University of Arizona Economic and Business Research Center. All data from October for preceding 12 months

Clearly, neither the parties divide of the Executive nor the economy’s performance alone can explain the substantial difference in regulatory activity among the three administrations. Personality, leadership style, administrative priorities and political philosophies of governance are key components in determining administrative agendas, including a regulatory one. Examining the types and costs of environmental regulation approved during this period, the rules about which few are ambivalent helps provide a window as to how regulation as an approach to governance fits within each administration.

Environmental Regulations

The Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ) manages all environmental programs within the state, including for air quality, water quality, solid and hazardous waste. Currently, the agency has more than 450 people supporting this wide range of programs, including both state only programs, like the Aquifer Protection Program, the Water Quality Assurance Revolving Fund and Voluntary Remediation Program, and federally-delegated programs for the Clean Air Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Hazardous and Solid Waste programs. Until the recent recession, the department was funded through a mix of state general funds, federal funds, and permitting/licensing fees; now, it must be entirely self-sufficient through permitting/licensing fees, federal funds and other non-appropriated funds. Its FY 2013 budget was about $134.5 million.

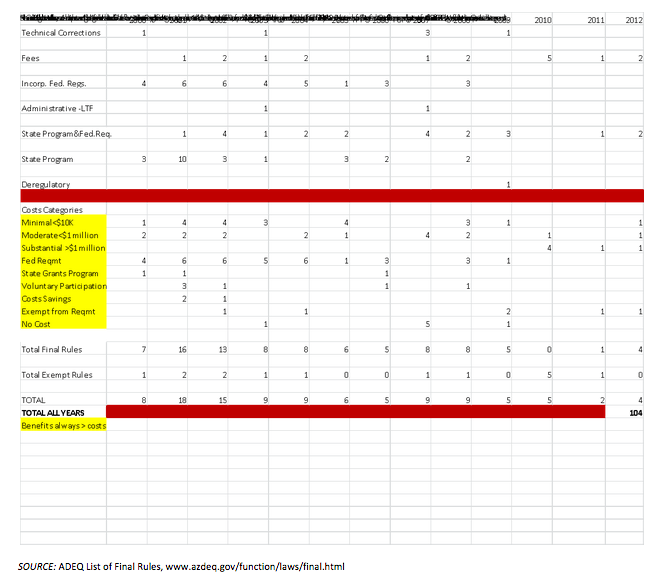

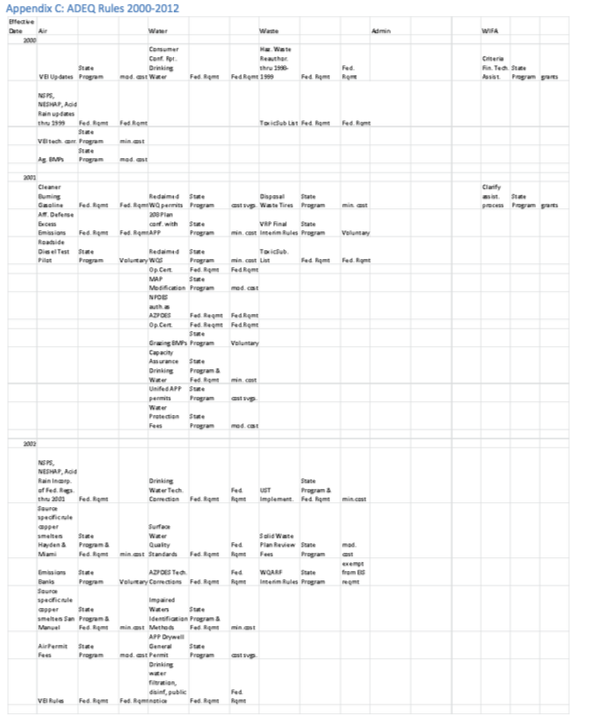

During the twelve-year study period, ADEQ records show a total of 104 rules finalized, including 15 rules that were exempt from the requirements of the Arizona Administrative Procedures Act and did not require GRRC approval. These rules were analyzed by type and cost to provide a detailed picture of the state’s environmental rulemaking. The type of rule categories include: technical corrections, which can be as simple as changing a name from “hearing board” to “Office of Administrative Hearings”; establishing fee schedules and amounts for permits, licenses, etc.; incorporating federal regulations into state rules, required for administering a federally-delegated program; administrative rules such as those prescribing licensing time frames; state regulatory programs, such as the Aquifer Protection Program (APP); and deregulatory rules that remove more stringent requirements or entire programs from rule, such as the repeal of the greenfield pilot program. Most state programs also contain a required federal regulatory requirement, but the water quality APP, the Pesticide Control and the Water Quality Assurance Fund (WQARF) programs are state only programs. Most rules are required to complete an assessment of its estimated impact on the economy, small business and consumers; exceptions include exempt rules, technical corrections, incorporation of federal regulations solely or rules where the Legislature has specifically exempted the requirement, such as for the WQARF program. Those rules that incorporate federal regulations typically do not conduct a separate economic assessment as the requirements were originally completed at the federal level and the rule incorporation is mandatory; benefits and costs accrue no matter the state’s action. Every rule analyzed for its economic impact showed benefits justifying the costs, although for many rules, costs and benefits are estimated based on inexact assumptions of who might need to comply with the program. Very few rules had the necessary specific information, such as the air quality copper smelter emissions rule (2002), where the regulated entity was singular and it was straightforward to generate detailed cost/benefit estimates. Most rules made assumptions based on industry-supplied data or small numbers of estimated costs. Overall, the economic assessments of environmental regulations are less robust than one would desire and could be improved by securing specific data from both affected businesses on the cost side and affected communities on the benefits side. Still, each rule prepared and approved explained its benefit/cost methodology, delineated assumptions, and included specific data when readily available. Unless someone petitions the agency to review its estimates two years following approval, however, little attention focuses on how correct the benefit/cost estimates are after rule implementation. While there is a requirement to include such an assessment within the agency mandatory 5-year review process, these analyses have been cursory and are not easily available for public review.A more comprehensive look back with public accessibility to the reports might be an additional reform to consider and could help dispel the idea that regulations are costly policy; most benefit/cost estimates conducted have erred on the conservative side. See Table 3, ADEQ Rules by Type and Cost for a picture of environmental rulemaking, 2000-2012.

Table 3: ADEQ Rules by Type and Cost, 2000-2012

SOURCE: ADEQ List of Final Rules, www.azdeq.gov/function/laws/final.html

A table listing all the environmental rules by name, program and type is included as Appendix C. Here, the depth and breadth of regulatory activity is readily apparent, particularly in the two year period 2001-2002 when a dizzying number of environmental regulations were approved. Thirty-three percent of ADEQ’s rules were incorporation of federal rules to administer federally-delegated programs. Most of these were required so that Arizona would be able to manage their implementation; in nearly every year of this study, rules were sought and approved to keep state rules for these programs synchronized with federal ones. Reasons for incorporating into state law federal requirements as soon as they are final plainly relate to regulatory certainty, so that there are no “dual” requirements in place and where the federal government through EPA would seek enforcement as a result of the regulatory gap. At the beginning of the decade, however, Arizona did not have “primacy” for federal Clean Water Act programs and had lost its authorization to manage the Hazardous Waste program. Securing the state’s ability to administer federal programs was a priority for both Governors Hull and Napolitano; Arizona obtained primacy for the federal National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) program (2001) that required incorporation of federal rules for several permitting programs including those for biosolids (2003) and concentrated animal feeding operations (2004), and reauthorization of the Hazardous Waste program (2000). Air quality was a special issue of concern during both administrations and ADEQ focused on strengthening efforts to reduce particulate emissions especially, through rules governing vehicle emissions, using cleaner burning gasoline and best practices for agriculture. Copper smelter emissions limits were revised and the state experimented with establishment of an emissions bank to allow for trading of credits.

In 2001, ADEQ simplified Arizona’s signature groundwater protection program, the Aquifer Protection Program, with its new unified permit, expanded the number of general permits available in lieu of having to obtain an individual permit, and developed a new permitting and water quality standards program for reclaimed water, a vital portion of the state’s water portfolio. Arizona’s water providers joined together to create a unique and innovative state program to assist small water utilities with their required drinking water monitoring, the Monitoring Assistance Program. Other major regulatory efforts included developing rules for the state’s signature “Superfund” program, the Water Quality Assurance Fund (WQARF) program, implementation of a revised Underground Storage Tank program, and development of a framework in which ADEQ would categorize as impaired the state’s surface waters.

About 40% of all environmental rulemaking completed from 2000-2012 occurred during Governor Hull’s administration. It was a mix of state incorporation of federal rules and important additions and changes to complex state programs, like the APP, WQARF, Voluntary Remediation Program and Underground Storage Tanks clean-up and remediation. The one rulemaking with substantial costs was done at stakeholders’ request –the Voluntary Remediation Program. The WQARF program also has substantial costs, but was developed by the business community and municipal providers to create a state funding mechanism to assist in remediation of contaminated sites so that the full cost of clean-up is not borne solely by those who may have contributed to the pollution, as the expense can be substantial. It is funded through a corporate income tax transfer directly to ADEQ. Most regulations approved during this administration had estimated minimal costs even as the environmental benefits were strengthened and advanced, and Arizona secured the ability to manage nearly every federal environmental program as a result. This was an active period for ADEQ and environmental regulation, with extended stakeholder participation from regulated entities and some efforts to widen citizen participation with neighborhood meetings for hazardous waste issues and multiple cities and towns listening sessions for drinking water rules, as examples.

About half (50%) of all environmental rulemaking during the period 2000-2012 occurred during the six-year administration of Governor Napolitano. Like Governor Hull’s administration, the Napolitano administration continued the effort to remain synchronized with federal rulemaking in the major environmental programs the state now managed: Clean Air, Clean Water, Safe Drinking Water and Solid and Hazardous Waste. Under Governor Napolitano, ADEQ was perhaps more aggressive in working regionally with other western state partners to develop state-based solutions to complex environmental problems like visibility and climate change. The development of the Reasonably Attributable Visibility Impairment rule set forth the process the state would use to determine whether Best Available Retrofit Technology (BART) would be required for sources contributing to visibility impairment in federal Class I areas (2003). While the federal government through EPA has ultimate authority for this program, ADEQ went forward with its own complementary interpretation of what was necessary for a source to comply. Similarly, the opacity standard (2004), the open burning rule(2004), work on a regional sulfur dioxide trading rule(2004), the hazardous air pollutants rule(2007), and Clean Car Standards(2008) arising from the state’s Climate Change Advisory Committee all provide examples of regulatory efforts to manage the environmental consequences of both accelerated population growth and its related challenge, climate change. Some of these rules carried substantial compliance costs to regulated parties, such as those born by coal-fired plants with the rule on standards of performance for mercury emissions (2007) or industry generally with the hazardous air pollutants rule. Others provided regulated parties needed flexibility to manage environmental problems within a changing environment, such as those made to the pesticides use rules (2005) and the APP general permits for onsite wastewater systems (2005). Throughout all this regulatory activity, estimated costs to comply with most rules were below the $1 million threshold of significant costs.

Stakeholder engagement changed slightly in composition during this administration and capitalized on the robust forms the agency developed during the Hull Administration. While regulated interests in business and industry continued their dominant involvement in agency rulemaking, groups outside the “usual suspects” were actively solicited to participate, like the Public Interest Research Group, the Arizona Lung Association, and smaller environmental organizations focused on a specific neighborhood like South Phoenix or specific issues such as maintaining stream flows. Throughout both administrations, ADEQ scheduled hearings and regulatory stakeholder meetings in various areas of the state outside of the major cities Phoenix and Tucson. However, citizen participation in nearly every aspect of state governance is difficult as the Legislature, the Governor and agencies typically hold meetings during the Monday through Friday, 8:00-5:00 work day, the same times and days most are employed elsewhere. Extra effort must be taken to open the process to other than paid lobbyists and salaried employees able to attend rulemaking meetings. Here, the state could learn from the productive and positive work of cities and towns, which hold meetings in the evening and invite citizen participation in a number of different ways.

Under Governor Brewer during this period, regulatory activity has been significantly limited. No rulemaking occurred in any of the state’s more complex environmental programs, save the incorporation of federal Clean Air Act regulations under New Source Review in 2012. Simple changes were made to the water quality operator certification program and the air quality emissions mine tailing management effort, technical corrections to air quality permitting programs, and the Clean Car Standards were repealed and the Greenfields pilot test program was eliminated. Other incorporation of federal rules in addition to the New Source Review rules took place with publication of the state’s required update of surface water quality standards; these rules were well underway and nearly final when Governor Brewer took office in 2009. Reflecting the economic problems the state has faced, in 2010 four exempt rulemakings (Legislative initiative) to raise fees occurred with each in the substantial cost category as ADEQ was directed to become self-sustaining financially. Additional fee increases occurred in 2011 and 2012, also with costs in the moderate (Solid Waste) and substantial ranges (APP, AZPDES and Hazardous Waste programs). Interestingly, more regulations approved during Governor Brewer’s administration have been exempt from the requirements of the Administrative Procedures Act that require public hearing and provide for more transparency through the GRRC process. Since these were rules providing for increased agency fees to generate revenue to support the agency so that general funds would not be used, time was essential to receiving sufficient funds for the agency to meet its payroll. Even so, it is clear that these rules were approved with fewer opportunities for public involvement, including from some who would need to pay the higher fees.

Unlike her predecessors, the Brewer administration has not kept pace with the state’s synchronization of its environmental programs with the federal rules. Awaiting action are amendments to the hazardous waste rules, the surface water quality standards, and the clean water act programs encompassed in the AZPDES program, all held in abeyance by the regulatory moratorium. The effect of the delay will not be immediate, but it creates uncertainty within the regulatory environment and leaves participants open to federal enforcement and litigation.

Summarizing the environmental regulatory environment from 2000-2012, there was substantial rulemaking activity during both the Hull and Napolitano administrations, nearly evenly split among air, water and waste programs, with associated costs estimated to be mostly in the minimal to moderate categories. The rulemaking balance among the agency’s environmental programs suggests an effort to keep pace with federal rulemaking in delegated programs, to advance public health protection with several air emissions and particulates control requirements, and in the state-only programs of APP, WQARF and VRP, to create credible, protective, and efficient environmental programs for the state’s groundwater resources. The Brewer administration had very limited rulemaking occur, but costs were high as the rules focused on fee increases as the agency shifted its funding sources due to loss of general fund revenue. No significant environmental rulemaking has occurred during this administration.

Both Governors Hull and Napolitano were very active in the Western Governors Association and the National Governors Association, and both were selected as leaders in those organizations by their peers; their views on issues like the environment, regulation and jobs rarely differed from those offered as consensus positions of those organizations. For Governor Hull, securing more state autonomy over federal programs and advocating collaborative, incentive driven, locally based solutions framed her actions and positions on environmental issues and regulation generally. She governed as a pragmatic conservative, recognizing the center as the place where she could achieve her goals. Governor Napolitano echoed those goals and added her own centrist focus on leading edge issues like reducing greenhouse gas emissions and renewable energy. These positions were consonant with both governors’ commitment to a robust and innovative economy focused on job growth and their leadership styles, more centered in the middle of the political spectrum, reflected the commitment to a collaborative approach. Governor Brewer has yet to assume leadership roles with either organization of governors, but is committed to trying to establish a robust economy and job growth. Her positions on environmental issues also argue for more state control over environmental issues, but are shaped more by political ideology and include concepts of rebutting federal requirements rather than simply managing them locally, an important distinction from Governor Hull’s more pragmatic approach.

Each governor’s personality, sense of practical versus ideological politics, view of stakeholder engagement and leadership style influenced the environmental regulatory activity occurring within their administrations. This finding is in concert with other research of state regulatory policies, which reflects the strong roles governors have, using personal and formal power, to influence the relative prescription of regulatory provisions.

Regulatory policy literature is filled with studies on the effects of environmental regulations on the economy, including specifically on employment. While there is no consensus on its effects, there are a substantial number of studies demonstrating environmental regulations have little to no effect on overall economic growth or jobs. In one key finding, detailed analyses of the environmental industry and jobs in Florida, Michigan, Minnesota, North Carolina, Ohio and Wisconsin demonstrate the overall relationship between state environmental policies and economic/job growth is positive, not negative.

The authors conclude that “states can and do have strong economies and simultaneously protect the environment; states with the strongest environmental records also have the best job opportunities and climate for long-term economic development.” The records of Governor Hull and Governor Napolitano seem to support this conclusion.

Conclusions

Our society governs itself, in part, through an umbrella of rules and requirements to ensure that the public good is not overrun by private interests. This shield of community protection must be constructed, however, in a manner that is complementary to America’s and Arizona’s capitalist based economy. Private sector innovation forms the foundation of robust economic growth. The benefits of any regulatory approach must always justify the costs to comply. The process by which regulations are crafted must be open to the public and opportunities for balancing interests need be emphasized and clear. Regulation is not something which is done to us as a society; it is what we require to make sure the market is efficient and fair and citizens are protected from the externalities of pollution, shoddy construction and manufacturing and unsafe food, drug and other products.

Regulatory practice in Arizona has been compatible with job growth and its benefits have consistently justified the costs. The policy innovations first initiated by Governor Babbitt continue to help make the state’s regulatory agenda transparent to the public and agencies’ conscious of costs. The efforts to manage federal and state programs in ways that provide a collaborative focus and locally based solutions have sustained the state’s environmental programs since 2000. We have done well in shaping a practical and comprehensive regulatory framework within Arizona, but there are always improvements to be had and the state’s public policy concerning regulation can benefit from a fresh look, which may be the best legacy of the self-imposed moratorium of the past four years.

First, implementing moratoriums against promulgating regulation doesn’t appear to effect job growth and may, in fact, have unintended consequences of causing harm, as they stop agencies’ abilities to advance their missions, potentially producing negative consequences for citizens. At the federal level, the U.S. Senate Sub-Committee on Oversight, Federal Rights and Agency Action recently conducted a hearing entitled “Justice Delayed: The Human Cost of Regulatory Paralysis” that heard how delays by Congress and the Administration on needed regulations have serious consequences for people’s lives. In Arizona, the recent upheaval at the Arizona Board of Medical Examiners was spurred, in part, by problems working within a framework of outdated rules that needed change. Ideological opposition to needed regulations helps no one, and has potential to do harm. Arizona should allow this self-imposed moratorium to fade away as soon as possible, but certainly as a new administration takes office in 2015.

Second, a better approach than moratorium to ensuring that regulations are effective and efficient is to fund the capability for agencies to perform stronger economic analyses of proposed rules and more comprehensive retrospective analyses of approved rules. It would be a positive step to include within agency 5 year reviews an assessment of the accuracy of the benefit/cost estimates included within the final rulemaking in addition to assessing whether the rule is accomplishing what it was proposed to do. In this way, agencies can refine their methodologies and regulated parties can more effectively determine the cost impact of a specific regulation. All parties would then be more confident of future benefit/cost estimates when made. Such an assessment might also provide all parties with the ability to see if technological or policy innovations have occurred that allow for a different approach to the problem the regulation was designed to address. Many of the air quality program rules, as an example, include such an approach. Adding this post-implementation analysis of benefits and cost will be more work for already overworked agency staffs, but additional funding targeted for these assessments would allow hiring third-party entities to perform the most labor-intensive part of the work. Other approaches to conducting these assessments could involve partnerships with Arizona universities, allowing senior graduate students opportunities to work on contemporary problems.

Third, making agency regulatory approaches and thinking even more transparent and inviting to the public at large will diminish the outsized role industry stakeholders currently have in writing regulations favorable to them. Instead of increasing the number of programs that do not need to participate in the GRRC public process through exempt rulemaking, the Legislature should return this regulatory territory to the Governor and allow the procedures well embodied in Arizona’s Administrative Procedures Act and GRRC’s own rules to frame how regulations are made and approved. This will provide a more consistent and equitable approach. We have regulation in the first instance because the market has failed; analysis of the ADEQ rules over this decade suggests a fine line exists between robust stakeholder participation from affected interest groups and stakeholder dominance of the process and final results. It is difficult for citizens not directly involved in a regulatory issue to take the time to participate; our daily lives are already full of activities that have a more immediate impact on our time. Every effort should be made, however, to increase citizen involvement where possible. Agencies do a very good job of providing online access to proposed rules and inviting comment through email; many agencies are increasing their use of social media to announce their activities. ADEQ, like other agencies, holds public meetings in various towns and cities throughout the state in an effort to engage communities more directly. The Arizona Administrative Register is the official source of state regulatory activity, but is not a popular read. State newspapers like The Arizona Republic and Arizona Daily Star and smaller, local news sources can do citizens a public service by publishing a regular column of key regulatory efforts, just as they do during the legislative session. In sum, more online communication through regular channels and social media, direct outreach in different communities throughout the state and greater attention through traditional media could extend the reach and purpose of agency regulatory work to more citizens throughout the state.

The tools and policy framework for effective regulation within Arizona are in place and have been for years. Let’s fine-tune our approach to sensible regulation, continue to craft fair and appropriate requirements and get rid of the myth of the regulatory burden as the killer of jobs. The regulatory state is both critically necessary and imperfect. The aim of our discourse should be neither to demonize nor discredit, but improve it.

Karen L. Smith, Ph.D. is a fellow of the Grand Canyon Institute and an adjunct professor at Arizona State University. Previously, Dr. Smith served as Water Quality Director at the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality and Deputy Director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources.

Reach the author at KSmith@azgci.org or contact the Grand Canyon Institute at (602) 595-1025.

The Grand Canyon Institute, a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, is a centrist think-thank led by a bipartisan group of former state lawmakers, economists, community leaders, and academicians. The Grand Canyon Institute serves as an independent voice reflecting a pragmatic approach to addressing economic, fiscal, budgetary and taxation issues confronting Arizona.

Grand Canyon Institute

P.O. Box 1008

Phoenix, AZ 85001-1008

GrandCanyonInstitute.org

Appendix A: Approved Final Regulations, 2000-2012

Appendix B: Economic Timeline

Appendix C: ADEQ Rules 2000-2012

SOURCE: ADEQ website, final rules, www.azdeq.gov/function/laws/final.html