Response Report

March 21, 2012

County Attorneys Criticism of Reducing Incarceration Costs while Maintaining Public Safety: GCI Response Evidence-Based Programs Work

Dave Wells, Ph.D.

Fellow, Grand Canyon Institute

The Grand Canyon Institute’s recent report “Reducing Incarceration Costs while Maintaining Public Safety: from Truth in Sentencing to Earned Release for Nonviolent Offenders,” and an op-ed that appeared on behalf of the Institute in the Saturday, March 3 Arizona Republic by GCI Board Member Bill Konopnicki was criticized in an op-ed piece that appeared in the Saturday, March 17 Arizona Republic co-signed by five County Attorneys: Bill Montgomery (Maricopa County), Barbara LaWall (Pima County), Daisy Flores (Gila County), Sam Vederman (La Paz County), and Brad Carlyon (Navajo County).

The Grand Canyon Institute appreciates our County Attorneys’ steadfast commitment to public safety. However, we wish they had taken a bit more care to review our report before criticizing it, as the Grand Canyon Institute purposely chose to focus on nonviolent offenders in the “ultra low,” “very low” and “low” recidivism risk categories developed by Darryl Fischer in his 500 page report that was released by the Arizona Prosecuting Attorneys’ Advisory Council.

GCI would much rather see our County Attorneys as allies than opponents in efforts to improve the efficiencies and outcomes of our criminal justice system. Incarceration has a role in criminal justice, but at a cost of $20,000 per year, for some nonviolent offenders, we have better options that are at least as effective and at significantly lower cost. Our County Attorneys are already heavily invested in programs to divert offenders from incarceration, which we applaud. The GCI report was intended to open a conversation about the structures of incentive-based programs, who might be eligible, and how best to structure the community supervision and drug treatment components that would need to accompany them. We hope they see merit in these ideas, and look forward to working with them constructively to reduce incarceration costs while maintaining public safety.

Positive interventions are far more impactful than negative ones, so earning release to community supervision has the potential to be a powerful motivator for inmates to change behavior.

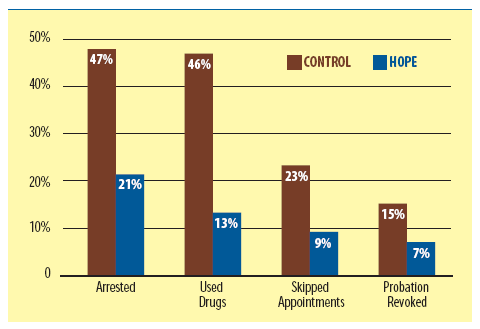

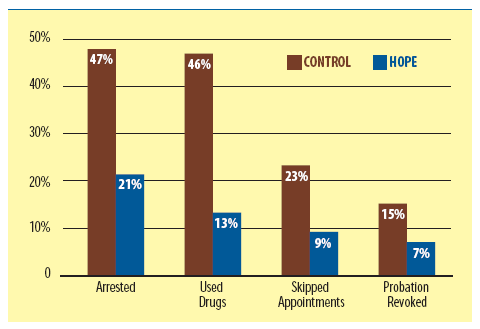

Recidivism rates are particularly challenging to lower. However, the criminal justice field has embraced evidence-based practices, which is what GCI encourages Arizona to adopt. For instance the HOPE (Hawaii Opportunity Probation with Enforcement) program in Hawaii has been particularly successful because it catches noncompliance well and applies swift and certain sanctions. The sanctions do not need to be severe, but they do need to be swift and certain. The HOPE program targeted high risk individuals, the hardest group to impact, while GCI had focused on low risk individuals. The results of the one-year randomized trial of the HOPE program are noted below.

(source: National Institute of Jusice, April 23, 2010, http://www.nij.gov/topics/corrections/community/drug-offenders/hope-outcomes.htm)

Below are the Grand Canyon Institute’s responses to the concerns expressed by the County Attorneys in their op-ed.

County Attorneys Concern: Funding Education or Prisons is a false dichotomy

“Overwhelming evidence and history clearly prove that we do not have to rob the criminal-justice system to cover the legitimate costs of education. Both are constitutional duties and responsibilities for Arizona.”

GCI response: Since 2002 the Department of Corrections budget increased 75 percent, while state general fund investments in state universities declined by 11 percent. Between rigid sentencing policies and a state fiscal crisis, universities were perceived as a discretionary expenditure. However, every state agency should seek to operate in the most cost-effective manner, including Corrections. GCI examined cost efficiencies that would not harm public safety (details below).

County Attorneys Concern: Konopnicki op-ed didn’t recognize the cause of prison population decrease.

“Konopnicki is correct in noting that Arizona is seeing a decline in its prison population for the first time. Yet this is not because we’re releasing more prisoners. It’s primarily because fewer people are being sent back to prison for minor or technical probation violations.”

GCI Response: Bill Konopnicki credited the Safe Communities Act and evidence-based initiatives at the county probation level, especially Maricopa County, as the cause of the prison population decrease. Reposted below:

“For the first time since we’ve kept prison statistics, Arizona has experienced a modest decline in its prison population. The reason has been evidence-based practices with our probation population, reducing those sent to prison. The Safe Communities Act of 2008, a bipartisan effort, sponsored by then State Senator John Huppenthal (R) gave county probation agencies incentives to reduce crime and violations rather than return offenders into state custody. Under the law, offenders earn 20 days off of their probation term for every month that they meet all of their obligations, including payment of victim restitution if it was ordered. The Grand Canyon Institute’s latest report “Reducing Incarceration Costs While Maintaining Public Safety,” notes that in Maricopa County alone the drop in probation revocations to prison saved taxpayers $27 million annually over costs in 2008.”

County Attorneys Concern: Konopnicki and GCI advocated putting felons “on the street” which would increase crime and negatively impact public safety.

“Konopnicki ignores the reality that putting inmates on the street would increase crime and the attendant costs on society. His misguided idea also begs the question: Who should be released? Konopnicki states that “nearly 20 percent of our prison population are non-violent offenders.” But he ignores the fact that this “non-violent” population includes people convicted of drug trafficking, multiple or aggravated DUIs, child molestation and other offenses classified as Dangerous Crimes Against Children.”

GCI Response: Using classifications developed in a report for the Arizona Prosecuting Attorneys’ Advisory Council, GCI identified a number of possible classifications of nonviolent offenders at low risk for recidivism as candidates for diversion or earned release to community supervision with drug treatment.

GCI didn’t advocate simply releasing people to the street, but to place nonviolent felons into evidence-based community supervision programs that would not impact public safety. The targeted categories offered included;

- First-time nonviolent offenders who were considered in the Fischer report as “ultra-low”, “very low” or “low” risk of recidivism.

- Nonviolent offenders convicted of class 4 to 6 felonies serving sentences of two years or less who also fell in these recidivism categories

- All nonviolent offenders who fell in these recidivism categories.

Truth in Sentencing for nonviolent offenders treats all offenders the same, when they are not. An inmate who refuses work assignments, uses drugs in prison, gets in fights, and enrolls in zero behavior modification programming serves practically the same prison time as an inmate who goes to work every day, stays drug free, attends all programming offered, has no disciplinary problems, and gets a GED.

Earned release would reward the second-type of inmate, while also helping reduce the likelihood of recidivism.

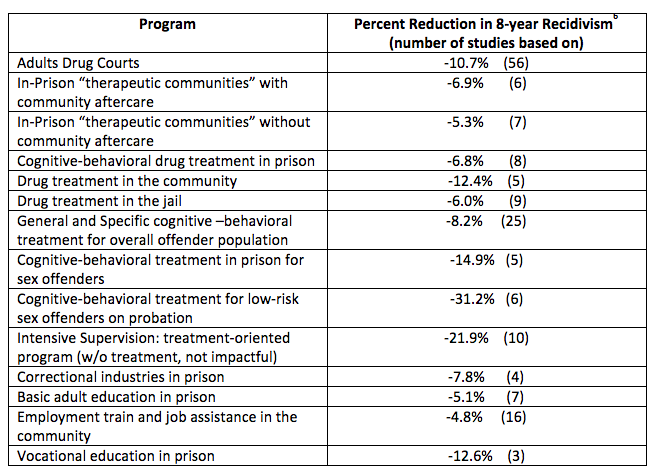

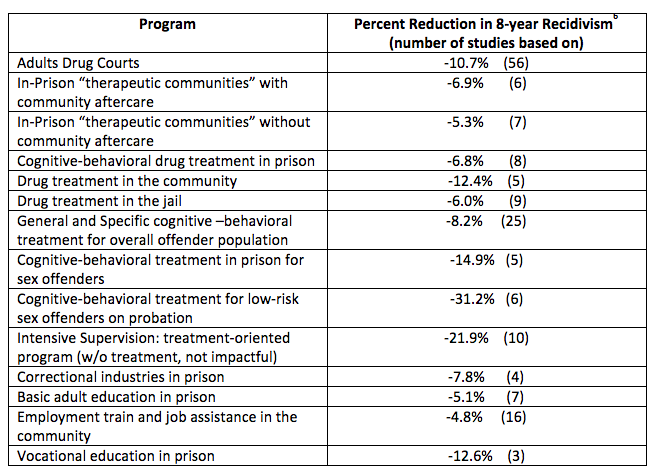

The most common new crime committed by those released (violent and nonviolent were not separated by the Fischer report for this) was Drug Possession and DUI, suggesting substance abuse issues remained after release, which is why drug treatment was mandated in the GCI recommendations for anyone with such a history who was released to community supervision. Currently only about 1 in eight inmates with significant substance abuse histories are receiving treatment in ADC. The GCI report lists evidence-based outcomes reproduced below that are designed to reduce recidivism as reported by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy, a research arm of the Washington legislature.

County Attorneys Concern: Cost savings doesn’t include cost of additional crime.

“Research data compiled by the Arizona Prosecuting Attorneys’ Advisory Council found that Arizona’s strengthened sentencing statutes have led to the incarceration of an estimated 3,100 additional offenders in Maricopa County since 2005 who would not have otherwise been imprisoned. Based on cost-of-crime models of leading crime economists, keeping these offenders off the streets prevented 98,038 additional crimes and generated a cost savings of more than $360 million dollars that would otherwise have been spent on crime-related damages to people and property.”

This is a shortened version of what has been written elsewhere: “The number of felonies by repeat offenders averages just under one per month. Under Arizona’s truth-in-sentencing laws, the average prison sentence is 33 months. Thus we have prevented approximately 98,038 additional crimes in Maricopa County alone. Assuming 90 percent of those deterred crimes (88,234) are to property with an average cost $1,900 each, that works out to a savings of $167 million. Assuming the remaining 10 percent (9,804) are violent offenses, which are generally estimated to cost $20,000 each, that savings approaches $196 million. Not only is this proof for the adage “crime doesn’t pay,” it supports the corollary – “incarceration saves” – to the tune of $363.7 million.”

GCI Response: Repeat felony offenders committing crimes once a month (and not always getting caught) does not sound like a group the Arizona Prosecuting Attorneys’ Advisory Council research report would classify as “ultra low”, “very low” or “low” risk of recidivism. Incarceration has its function, but what happens afterwards is equally important.

One of the primary functions of prison is to incarcerate those who would otherwise be victimizing law abiding citizens. However, an equally important question is what’s happening after 33 months? Are these individuals returning to their life of crime? Our guess is that absent systematic interventions to improve their odds of success, this is crime that is temporarily avoided, not permanently avoided.

County Attorneys Claim: Truth in Sentencing is why Arizona’s crime rate has dropped faster than the national average.

“Incapacitating these criminals is certainly one reason Arizona is enjoying a much larger drop in crime than the nation as a whole. Releasing prisoners will not save money. It will not make us safer. And it will certainly not help our education system. To argue otherwise is irresponsible and inconsistent with an intelligent public-policy-making process.”

GCI response: The causality in this claim lacks merit; the decline in Arizona’s crime rate occurred nine years after Truth in Sentencing was adopted.

Of course, if you incarcerate more people, they cannot commit more crimes. However, we don’t find that the states with the highest incarceration rates have the lowest crime rates. Truth in Sentencing was adopted in Arizona in 1994, yet it’s not until 2003 that Arizona experiences the first of a succession of years in declining crime rates. Despite that decline, Arizona’s crime rate still exceeds the national average. The sources of that decline are definitely worth exploring, but the prima face evidence does not suggest Truth in Sentencing, especially for nonviolent offenders, is responsible.

Dave Wells holds a doctorate in Political Economy and Public Policy and is a Fellow at the Grand Canyon Institute.

Reach the author at DWells@azgci.org or contact the Grand Canyon Institute at (602) 595-1025.

The Grand Canyon Institute is a centrist think thank led by a bipartisan group of former state lawmakers, economists, community leaders, and academicians. The Grand Canyon Institute serves as an independent voice reflecting a pragmatic approach to addressing economic, fiscal, budgetary and taxation issues confronting Arizona.

Grand Canyon Institute

P.O. Box 1008

Phoenix, AZ 85001-1008

GrandCanyonInstitute.org

Criminal Justice

Criminal Justice