Criminal Justice

Criminal Justice

Reducing Incarceration Costs While Maintaining Public Safety: From Truth in Sentencing to Earned Release for Nonviolent Offenders

March 5, 2012In FY 2002 the state of Arizona’s general fund investment for universities was 40 percent higher than its expenditures for the Arizona Department of Corrections (ADC). During the decade that followed, nominal (current dollars) corrections spending rose 75 percent, while universities received nominal cuts of 11 percent. Consequently in FY2012 Arizona is now spending 40 percent more on corrections than on universities.

Thirty percent of those behind bars in Arizona are nonviolent offenders, who have never been convicted of a violent offense.2 Arizona is the only state in the country that applies “Truth in Sentencing” to nonviolent offenders. The statute mandates an offender serve at least 85 percent of their sentence behind bars. This policy is not cost effective. The Grand Canyon Institute (GCI) estimates that incorporating policies from other states could save the state between $30 and $73 million annually without hindering public safety depending on how structured. In addition, the state could save millions in accompanying prison costs, as such changes in policy would alleviate the need to build new state prisons or establish contracts with private prison providers.

Policy Paper

March 5, 2012

Reducing Incarceration Costs While Maintaining Public Safety: From Truth in Sentencing to Earned Release for Nonviolent Offenders

Dave Wells, Ph.D.

Fellow, Grand Canyon Institute

In FY 2002 the state of Arizona’s general fund investment for universities was 40 percent higher than its expenditures for the Arizona Department of Corrections (ADC). During the decade that followed, nominal (current dollars) corrections spending rose 75 percent, while universities received nominal cuts of 11 percent. Consequently in FY2012 Arizona is now spending 40 percent more on corrections than on universities.

Thirty percent of those behind bars in Arizona are nonviolent offenders, who have never been convicted of a violent offense. Arizona is the only state in the country that applies “Truth in Sentencing” to nonviolent offenders. The statute mandates an offender serve at least 85 percent of their sentence behind bars. This policy is not cost effective. The Grand Canyon Institute (GCI) estimates that incorporating policies from other states could save the state between $30 and $73 million annually without hindering public safety depending on how structured. In addition, the state could save millions in accompanying prison costs, as such changes in policy would alleviate the need to build new state prisons or establish contracts with private prison providers.

Introduction

For the first time ever, Arizona had a reduction in the number of people incarcerated between FY2009 and FY2010 and since then the prison population has remained stable. The credit is partially attributed to the Safe Communities Act of 2008, sponsored by the State Senator John Huppenthal (R) that expanded the ability of counties to divert low-risk offenders to probation rather than prison. Under the law, offenders earn 20 days off of their probation term for every month that they meet all of their obligations, including payment of victim restitution if it was ordered. In its first two years, new felony convictions by probationers fell 31 percent, and revocations to jail dropped 28 percent and revocations to prison plummeted 39 percent. The Pew Center on the States estimates it has saved the state $36 million. A key contributor to the success has come from the Arizona county adult probation departments who have adopted evidence-based practices which have enabled sharp reductions in probation revocations to prison. For instance, for Maricopa County Adult Probation the number of revocations to prison dropped 1,601 comparing 2008 to 2011, representing an annual cost savings of up to $27 million, and a cumulative cost savings of up to $54 million over incarceration across the three years.

Drug Induced Crime and Treatment

Drug-induced crime drives much of the behavior of the individuals currently within the Arizona Department of Corrections (ADC). While Arizona in 1996 voters passed a ground-breaking effort to mandate treatment instead of prison time for first and second time drug users. As amended by voters via legislative referral it excluded methamphetamine users from treatment and many nonviolent felons who desperately need drug treatment are bypassed. As a consequence only a fraction of those who could benefit from drug treatment are receiving it, and Arizona taxpayers consequently pay $20,000 a year to warehouse many individuals whose underlying drug problems motivate their criminal behavior—and if not addressed before release, too many times, they’ll fall into the same trap. That’s not only a tragedy for the released inmate, but to all those who are hurt by repeated criminal behavior, as well as taxpayers who must pick up the tab for a revolving door that’s not addressing substance abuse issues.

The Arizona Department of Corrections’ Data & Information for Fiscal Year 2011 notes “In FY 2010, 1,810 inmates completed substance abuse treatment. Substance abuse treatment services include moderate and intensive treatment, methamphetamine treatment, co-occurring disorder treatment, and DUI treatment.” However, it also indicates that “Seventy-five percent of inmates assessed at intake have significant substance abuse histories.” That number may be an understatement as the Appropriations Report for the Department of Corrections for Fiscal Year 2005 noted that 92 percent of inmates had addiction problems. GCI uses the average, 83.5 percent, as the presumed portion of inmates needing substance abuse treatment.

When we consider how many inmates came through intake in FY2011, we get a sense of the huge gap. 18,759 new inmates were brought into the Department of Corrections in FY2011. If we consider only these as the number who were eligible for substance abuse treatment, then less than 10 percent completed it. In addition, another 19,055 inmates were released from custody in FY2011, the number completing treatment is also less than 10 percent. Of course, these individuals overlap little, so no matter how you read it the availability of treatment falls far short of the need.

Diversion and Earned Release Credits as Alternatives to Imprisonment

Considering that alternatives to incarceration are most effective for those at lowest risk off recidivism, based on prison population data from March 31, 2011. GCI’s review of those incarcerated within the Department of Corrections reveals that Arizona can move at least 1,900 and potentially as many as 8,400 inmates to some form of community supervision without risking public safety. At minimum 1,900 nonviolent offenders could be removed immediately and the additional 6,500 offenders should be incentivized to where their sentence can be reduced and they can be moved from incarceration at a cost in excess of $20,000 a year to some level of community supervision that depending on the degree of supervision mandated costs between $1,500 and $8,000 per person. However, until Arizona addresses its inflexible “Truth in Sentencing” laws, such discretion is not possible, even though the Arizona Department of Corrections considers these inmates “low risk,” “very low risk” or “ultra low risk” for recidivism, and the older inmates among them are placing large health care costs on the Department of Corrections.

Recommendation: Replace Truth in Sentencing for nonviolent offenders with low risk nonviolent offenders diverted to community supervision system and/or make nonviolent offenders eligible for earned release to community supervision after 50 percent of their sentence is served.

Option A: Implement a community supervision diversion with drug treatment, if needed, for all low-risk first time nonviolent offenders and for low-risk repeat nonviolent 4-6 class felony offenders currently serving sentences of two years or less, excluding those on ICE detainers. 1,900 offenders impacted. Cost Savings $30 million annually.

Option B: Adopt earned release time for nonviolent offenders such that they can leave prison after 50 percent of their sentence is served and move to community supervision with drug treatment, if needed. Those successful reduce their time in prison by 40 percent (serving 50 percent instead of 85 percent). 8,400 to 11,350 offenders impacted (GCI assumes 8,400 achieve reduced sentences). Cost Savings $55 million annually.

Option C: Adopt both Options A and B. 1,900 offenders impacted under Option A and remaining 6,500 impacted under Option B. Cost Savings: $73 million annually.

Community Supervision comes in many degrees. At the high end is intensive probation for those at highest risk to commit another crime. Requirements include

- Maintain employment or full-time student status or perform community service at least six days per week;

- Pay restitution and monthly probation fees;

- Establish residency at a place approved by the probation team;

- Remain at their place of residence except when attending approved activities;

- Allow the administration of drug and alcohol tests;

- Perform at least 40 hours (with good cause the court can reduce to 20 hours) of community restitution work each month except for full-time students, who may be exempted or required to perform fewer hours; and

- Meet any other condition set by the court to meet the needs of the offender and limit the risk to the community.

In addition, probationers must make visual contact up to four times a week with officers and sometimes that occurs at places of employment or at home. Intensive probation costs a bit under $8,000 per year per probationer; GCI uses $8,000 as the annual cost.

Standard probation may involve many of the elements of intensive probation, though the levels are less, such as one to two visual contacts per month instead of up to four times a week. With evidence-based practices, probation departments work to help build the ability of probationers to succeed in society. Standard supervision costs slightly less than $1,500 annually. GCI uses $1,500 as the annual cost. The Arizona Department of Corrections finds its average cost for community supervision is about $3,000 annually per person.

The state pays $20,000 for minimum security but only $3,000 annually for those put under community supervision, if evidence-based procedures are followed with community supervision, public safety will remain protected. To the community supervision cost GCI adds an additional $1,150 for those with substance abuse issues, as treating substance abuse issues is one of the most critical pieces in reducing recidivism.

Based on the Arizona Prosecuting Attorneys’ Advisory Council Prisoners in Arizona, December 2011 report by Darryl Fischer, Ph.D. as of March 31, 2011, the number of low risk nonviolent offenders that could be moved from incarceration to community supervision numbered 1,870.

The Fischer report indicates the number of nonviolent first offenders, a low-risk group, as representing 87.9% of the 1,966 such offenders as of March 31, 2011. This yields 1,728.

In addition, the Fischer report examines those sentenced for up to two years for class 4-6 felonies who are also nonviolent offenders and deemed to be low risk. This group totals 1,671. However, one-third of these are nonviolent first-offenders, so the remaining two-third (technically 66.8%) are new individuals, yielding a net low risk pool of nonviolent offenders of 2,844.

974 of these nonviolent offenders are under ICE detainers as they are immigrants not legally present in the state and face deportation. GCI presumes that this group would remain incarcerated as they might be an excessive flight risk.

Hence, 1,870 individuals based on the report by the Arizona Prosecuting Attorneys’ Advisory Council are low risk who could be much more cost effectively dealt with if moved to community supervision and given drug treatment, if needed. If that was done and drug treatment provided, the state would save $30 million annually with no impact on public safety. GCI denotes this as Option A.

At least 321 of these individuals are currently serving mandatory sentences, which would need to be addressed to allow for more flexible sentencing for these offenders. Likewise, truth in sentencing laws would need to be altered for nonviolent offenders. “Truth in Sentencing” requires that inmates serve at least 85 percent of their sentence before release.

Arizona was one of only two states in the country to apply “Truth in Sentencing” to nonviolent offenders. Mississippi was the other. However, Mississippi in the last eleven years has determined the policy fiscally ineffective and made substantial changes. In 2001, Mississippi restored parole-eligibility to first-time nonviolent offenders after they had served a quarter of their sentence. This was expanded in 2008 to include all nonviolent offenders including those convicted of selling small quantities of drugs. Of the 3,100 individuals released from 2008 through 2009, only 121 had been returned to prison as of 2010, and only five of those were for new crimes, the remainder was for parole violations. Mississippi’s changes have saved the state an estimated $200 million.

The Washington State Institute for Public Policy (WSIPP) studied the impact of their 2003 law that increased earned release credits for nonviolent offenders from 33 percent to 50 percent of their sentence, and they found a net public safety benefit and significant taxpayer savings compared to a matched control group. Their only inferred cost of reducing sentences, an assumed increase in property crimes from shorter sentences can be effectively mitigated by transitioning prisoners to appropriate levels of community supervision based on their potential recidivism and providing adequate transitional services to ensure a more successful reintegration into society.

Earned release credits require participants to exhibit good conduct, and participate in ADC programs such as work, education, drug treatment, and other approved programs. Credits can be lost as a consequence of inappropriate behavior. Hence, these programs give inmates an incentive to behave and improve themselves. Community supervision also helps move inmates into the workforce and enables restitution payments, community service, as well as partial reimbursement for monitoring costs, such as use of GPS tracking devices.

As of March 31, 2011, ADC incarcerated 9,385 inmates who have never been convicted of a violent offense and are classified as “low risk”, “very low risk”, or “ultra low risk” of recidivism. Removing those with ICE detainers leaves 8,411 who could potentially be eligible for an expanded earned release credits or an early parole, if “Truth in Sentencing” and obstacles were removed. Assuming Arizona adopted an earned release rate where sentences could be cut in half and presuming that currently low risk nonviolent under current law serve 85 percent of their sentence behind bars, then 40 percent of this population group at any point once fully implemented would be moved to community supervision with drug treatment as needed, yielding $55 million in savings. Technically, the savings might be greater, as 11,350 total inmates in ADC fall in this category, but 2,939 of them had higher recidivism risk ratings. Most, if not all, of these prisoners would also qualify for reduced sentences, and most importantly they would be incentivized to participate in programs that would have the net impact of lowering their recidivism risk through earned release. However, GCI uses the more conservative number of 8,411 presuming that only the low risk offenders successfully reduce their sentences. This is Option B.

Combing deferment to community supervision and drug treatment for low risk first time nonviolent offenders (Option A) and low risk repeat nonviolent offenders who would otherwise be serving two years or less for felonies class 4-6 (Option A) with the 50 percent earned release credit for all other nonviolent repeat offenders (Option B) yields a net savings of $73 million (Option C).

Hence, removing truth in sentencing for nonviolent offenders would save the state between $30 and $73 million annually depending on how structured. GCI has intentionally tried and make these estimates conservative.

Additional Savings: Not Building Prisons

In addition, the state could save millions in accompanying prison costs, as such changes in policy would alleviate the need to build new state prisons or establish contracts with private prison providers. As an illustration consider the recent completion of 4,000 minimum security beds in Perryville, Yuma and Tucson. Construction included 1,000 female beds in Perryville, 2,000 in Yuma and 1, 000 in Tucson. The state entered a 20-year lease purchase back contract for $200 million to build and finance the facilities. In addition, the fiscal year 2011 budget included $7 million dollars for equipment in one-time start up costs for the new facilities. When the state engages in contracts with private prisons, the contract fee includes payments over the length of the contract to pay for the facility. While overtime, it’s much more expensive to operate the prisons than to build them, the state still can save millions of addition costs. Had, for instance, the options discussed above already been in place, the state would by GCI’s estimates have about 1,900 fewer people behind bars with Option A, about 3,360 fewer incarcerated with Option B, and 4,500 less prisoners with Option C.

Hence, although the 4,000 bed capacity was developed in large part to deal with overcrowding (double and triple bunking existing prisoners), Option C would save the state more than $207 million in future prison construction costs.

Reducing Recidivism

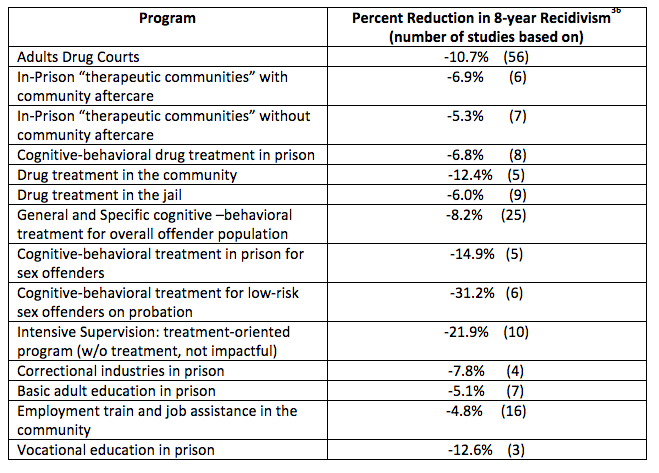

Beyond punishment, criminal justice systems should aim to lower the likelihood of future crime among those in it. In 2006 WSIPP examined a number of programs across numerous studies and noted the following significantly reduced recidivism.

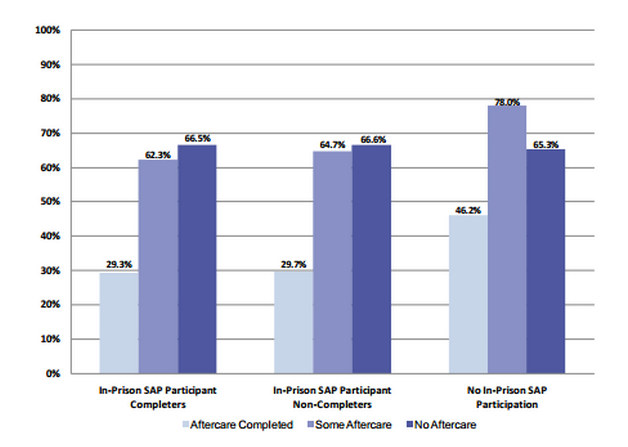

In California, researchers looked at the impact of drug treatment in prison with aftercare compared to cases with no aftercare and no treatment, and found that successfully completing treatment in prison led to a 50 percent reduction in three-year recidivism. See figure from that study below:In another study of evidence-based treatment for mental illness and alcohol and drug abuse, WSIPP found $2.05 in benefits for taxpayers for every $1 spent.

Conclusion

Arizona through its evidence-based work in adult probation has shown that alternatives to incarceration can both help offenders succeed and save the state money without imperiling public safety. It’s time for Arizona to take the next step by replacing “Truth in Sentencing” for nonviolent offenders with community supervision diversion programs and/or establish a 50 percent earned release program, whereby inmates who successfully complete evidence-based programs that reduce recidivism are rewarded with reduced prison time that is replaced with some kind of community supervision.

Such policies would save the state between $30 and $73 million annually, while maintaining public safety. However, these savings are not possible unless the legislature acts to enable more flexible and effective means of dealing with nonviolent offenders, much like they did in 2008.

Dave Wells holds a doctorate in Political Economy and Public Policy and is a Fellow at the Grand Canyon Institute.

Reach the author at DWells@azgci.org or contact the Grand Canyon Institute at (602) 595-1025.

Grand Canyon Institute

P.O. Box 1008

Phoenix, AZ 85001-1008

GrandCanyonInstitute.org

Appendix: Estimating Marginal Costs of Prisoners

In economics, differentiating average and marginal costs are important, and within the criminal justice realm, a failure to properly apply marginal costs could lead to an over estimation of savings.

The Department of Corrections offers its own marginal cost figure of $12.60 per day to feed, shelter, and supervise one additional inmate. This is substantially less than the $55.59 average daily cost attributed to minimum security inmates.

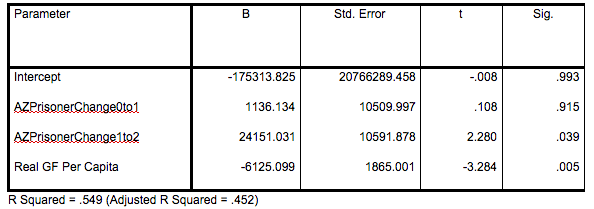

The Washington State Institute on Public Policy, connected to their state legislature, has looked at marginal cost analysis using budget numbers to estimate in practice marginal costs. Their analysis for the state of Washington identified a lagged effect for long-run marginal costs, suggesting while initial costs might be in line with what the Department of Corrections uses that when changes in prison populations are sustained over time the marginal costs rises markedly. Their model lags prison population changes over four years for the best fit. For Arizona the Grand Canyon Institute followed a similar model. As with WSIPP, GCI identified the year over year change in spending for the Department of Corrections. GCI did not have access to prison only-expenditure data, so full expenditures from the General Fund were used instead. The first year that the Department of Juvenile Corrections is separated out from the Department of Corrections was in FY1990, so only data from FY1990 through FY2009 were used. Due to the use of lagged variables, the full data set was from FY1992 with some variables lagged back to FY1990.

The WSIPP model regresses the real change in corrections spending on the year to year changes in the prison population counted back along with an economic strength measure, real per capita income. They use the consumer price index as an inflation adjustment.

GCI makes a couple modifications. The market basket of the consumer price index does not match well with the expenses of state government, so instead GCI used the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ State and Local Government Price Index, which weights personnel cost as the most significant factor. While it may not exactly measure actual price inflation in Arizona, we feel it was a more appropriate measure for adjusting for the impact of inflation.

The use of real per capita income was not a statistical significant factor in the model developed by WSIPP. However, certainly economic circumstances do impact the strength of the General Fund as well as tax policy changes. Hence, as an economic measure, GCI used instead the Real General Fund Expenditures per capita using the state and local government price index.

After exploring the impact of lagged year to year prison population changes, we found that only a two year lag was necessary in Arizona. So for instance, in 2009 that would mean the prison population change from 2008 to 2009 and the prison population change from 2007 to 2008. Extending prison population changes beyond two years added no further explanatory power to the model.

The net result for Arizona we found was a model which is statistically significant in estimating the growth of the state budget for the department of corrections as noted below.

Statistically, the model has an F value of 5.673, indicating it does an exceptionally good job of estimating the dependent variable, changes in the Department of Corrections budget using 2005 dollars.

With respect to specific parameters, the coefficients on the prison population changes are the estimated marginal costs. Hence, the change over the past year has a coefficient of $1,136 is substantially less than the $4,600 marginal cost developed from a $12.60 daily cost used by the Department of Corrections. However, that coefficient fails a statistical significance test for it to be nonzero. What’s more relevant is the coefficient on the prison population change between one and two years prior. The coefficient on that $24,151 is statistically significant at the 95 percent level as nonzero. Furthermore it was particularly robust changing very little across numerous specifications of the model. The total marginal cost is the sum of the coefficients on the one and two year changes in the prison population, $25,291, which is on par with the average inmate costs reported by the Department of Corrections. Hence, GCI concludes that the Department’s marginal cost estimates are accurate only for the first year, but sustained changes to the prison population lead to marginal costs that more or less equal the average cost per inmate. Therefore, we use the average cost provided by the department of corrections based on their actual expenses incurred.

The real General Fund expenditure per capita was also statistically significant and has a coefficient of -$6,125 means that when the budget is more flush, corrections doesn’t do as well as other parts of the budget, but when the budget is tight, corrections maintains or increases funding when other parts are cut. We’ve certainly seen that over the last ten years where in nominal terms corrections funding has risen by 75 percent while universities have been cut 11 percent.