Following the Money: Twenty Years of Charter School Finances in Arizona

(A Meta-Analysis of Charter School Financials and what they tell us) By Curtis Cardine, Fellow, Grand Canyon Institute

Co-Authored with Dave Wells, Ph.D., Research Director, Grand Canyon Institute

Download the Full Report here

For details on the full methodology go here.

The Essential Questions Explored in these Policy Reports

“What have the promoters of charter schools done with the freedom over their budgets, staffing, curricula and other operations?”

“What is the result of eliminating the substantial conformity of governance and finance rules for operating schools (financed from taxpayers’ dollars) on the governance and finances of these entities?”

Executive Summary

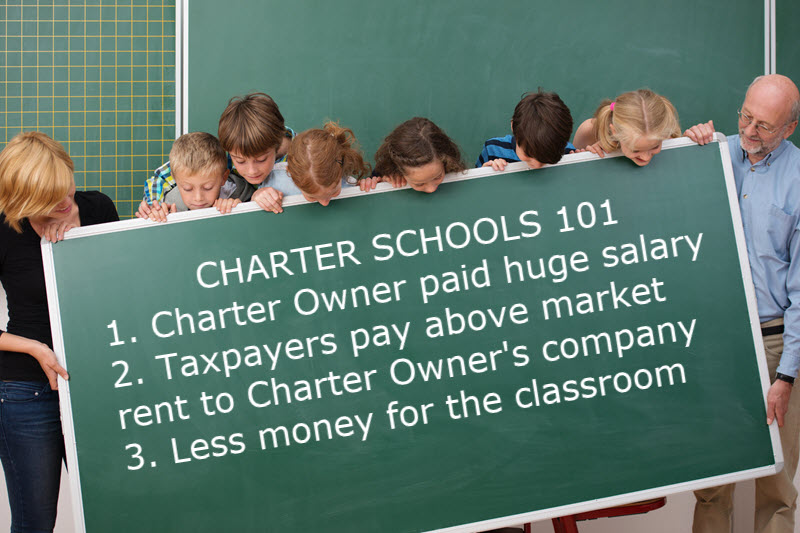

While school choice and free market economic theory have driven the Arizona charter school movement, many in the drivers’ seat have found opportunities to benefit themselves through financial transactions that are specifically forbidden in public district schools. Charter schools were promoted as competition to the public school system. The “rule books” regarding financial controls and governance were replaced by laws that eliminated most oversight. Fundamentally, charter schools do not offer parents and their children true school choice when they operate without the financial accountability and transparency demanded of ‘competing’ public district schools. Charter holders receive almost all their funding directly from the State’s General Fund on a per student basis. In FY2016 charter schools received $6,669 per student from the State’s General Fund, representing about 85% of their funding. Almost all of the rest comes from the Prop. 301 education six-tenths of a cent sales tax and the Federal Government (Joint Legislative Budget Committee 2017, Arizona Department of Education 2016). This extensively researched policy report, the first in a series of three reports, highlights some of the differences in the rules that govern public district schools and charter schools. Charter schools were given greater freedom over their budgets, staffing, curricula and other operations to foster quality improvements in the education they provide and to encourage competition. This policy report, and the others in this series, look at the actual business practices that emerged from that greater freedom from regulations, focusing on the following areas: related-party transactions, high executive compensation compared to comparable public sector salaries, questionable distributions of profits/owner’s equity, lower classroom spending, academic underperformance, and inconsistent financials. Related parties1, while usually actual relatives of the charter holder, also includes related businesses (businesses with the same board and owners), and former charter holders that still engage in business with the charter group. Current financial practices by most charters fall short of sound business practices and the public’s expectations as to how their educational dollars should be spent (Bennis, Parikh, and Lessem 1994, Dewey 1891, Knight and Friedman 1935, Pojman, Vaughn, and Vaughn 2014).

Recently, KAET Horizon host Ted Simons asked Governor Doug Ducey if there was enough oversight with regards to where Empowerment Savings Account money directed to private schools. The question related to SB1431 that he had signed expanding state- funded Empowerment Savings Accounts for private schools. The Governor responded, “We want to have transparency and accountability. We can do that.”(2017) Transparency and accountability should also apply to the state’s hundreds of privately owned charter schools. This policy report’s findings articulate the need for greater transparency and accountability in the charter school sector. In the absence of a definitive legal standard for accountability, charter holders and their corporate boards have created financial arrangements that benefit ownership at the expense of students and teachers.

Related Parties Transactions: Three-fourths of Arizona’s charter school holders engage in related-party transactions that did not fit the definition of “saving money” or “efficiency,”an oft-cited reason given for allowing charters to engage in this practice. Gaming the system is often done through contractual transactions with subsidiary for profit companies owned by the charter school holder and overseen by the same corporate board as the nonprofit charter school. In 2013-14, 48% of Arizona’s charter school expenditures for contracts, leases and rents were owed (committed) to for profit companies that employed or were owned by the charter holder or a related party. These commitments amounted to $497.5 million annually. That figure would be higher if administrative and teacher salaries and benefits to related parties were included.

Key Recommendation: Require publicly funded charter schools to be subject to the same public competitive bid procurement process as district schools. All related party contracts need to be public information and need to meet the standard of saving money for educating students.

Excessive Executive Salaries: Numerous cases were found where charter administrators’ salaries are shockingly high for the number of students they oversee. In one case, the executive director of a youth center that also includes a 90-student, single- location charter is paid as much per year as a public school superintendent who oversees 23,000 students. Adding insult to injury, the school in question received failing academic marks from the Arizona State Board for Charters Schools.

Key Recommendation: Require charter school audits to justify executive and administrative salaries benchmarked to comparably sized district schools.

Questionable Distributions’s2 of Profits: One-third of for-profit charter schools were found to have made questionably large distributions to their shareholders. Six for-profit charter schools made distributions valued at 12% to 45% of their 2014-2015 state taxpayer revenue. Four for-profit charter schools took more than their net profit as distributions, turning a net profit for the year into a net loss as a consequence. While large distributions might come from accumulated retained earnings, they can also undermine the financial viability of the operation. The data on distributions from subsidiary for profits, operated by the same owners and board as many nonprofit charters, is unavailable to the public as the firms are considered separate businesses from the charter. Where that information is discernable through forensic accounting, it is provided.

Key Recommendation: Charter school audits need to identify the source of any profit distribution and the ASBCS would need to approve any distribution that exceeded net profits for the year.

Reduced Classroom Spending: The losers in this mix appear to be taxpayers, teachers and students in a majority of cases. Charter school teachers on average earn 20% less than their public district school colleagues while 43% of charters do not offer a retirement or savings plan to their employees. This issue is explored in depth in the third policy report of the series. The 2013-2014 Annual Report of the Superintendent for Public Instruction showed that charter schools spend 45% of revenues on classroom instruction compared to public district school spending at 52% of revenue. At the end of Fiscal Year 2015 the numbers were 51.5% for District Classroom Spending and 47.5% for Charter Classroom Spending. Student Support Levels at Charters was 4.9% to Districts at 7.9%. This information is not widely known because these figures are buried in the Annual Report. The data on which they are based, AFRs, are not scrutinized for accuracy for charter schools and is sometimes inaccurately entered. Another issue that is explored in this report is inconsistent financial accounting to the state, IRS and on the audits. From related party transactions to excessive executive compensation to questionable distributions to shareholders, revenue from the state’s General Fund designated for educational purposes instead disproportionately benefits the charter school holders and corporate board members of charter schools.

Key Recommendation: Charter school financial data needs to be shared and monitored by the Auditor General just as is done with district schools.

Academic Underperformance: This financial behavior may have academic consequences (although academic performance is NOT the focus of these papers). Despite the highly esteemed academic profile of a few charters, the charter sector overall underperforms academically relative to district schools for students of similar demographic backgrounds in the same area. Two independent studies found demographically similar students did just as well or better on average in public district schools.

Reconciling Inconsistent Financials: Frequently numbers in charter school annual financial reports (AFRs), audits, and IRS filings do not reconcile even though they cover the same period. Some audits are inadequately detailed and done by out-of-state firms that may not be familiar with Arizona law. For instance, in 2014-2015, one charter holder that currently runs two schools reported a net gain in revenues less expenses of $369,000 to the Arizona Department of Education (ADE) and yet their audit noted a net loss of $134,000 to the Arizona State Board for Charter Schools (ASBCS) for the same year. The difference in total net assets reported in their audit and to the IRS were also dramatically different in fiscal 2013-2014. The IRS 990 reported $2.5 million in net assets, while the audit indicated negative net assets of $2.6 million, a $5.1 million difference!

Key Recommendation: Require a standard format for audits and ensure that audits, AFRs and IRS 990 filings numerically align with one another.

Notably, one-fourth of charters are providing the opportunities promised by their founding legislation. In the absence of sufficient financial oversight, they do the right thing. A large charter that is an exemplar of this type of organization is the Arizona Agribusiness and Equine Centers. These charters should be emulated and replicated. Their business models are financially sound and ethical. They also treat their teachers fairly and as professionals.

This policy report and the policy reports that will follow are designed to give information to the public and policymakers. The information should serve as a timely financial warning. These policy reports are informed by three years of exhaustive research and a forensic accounting of the data including a meta-analysis of the most comprehensive financial data on Arizona’s charter school sector. Sources include AFRs, audits, Federal IRS 990s for nonprofits. The ASBCS and the ADE were consulted and were helpful during the information gathering phases of this effort. Their assistance was greatly appreciated. Preliminary findings were shared with these agencies. Each section of this report offers specific recommendations designed to improve information for parents, achievement for students, and accountability to taxpayers. The next in this series of policy reports, due to be released in the fall, will look more carefully at red flags regarding issues with financial management, growing debt with many charters, and whether current business practices are appropriate and sustainable. A failure rate of 42% since 1994 is one symptom that charter finances and governance need attention. In the fiscal year ending June 30, 2015, a total of 138 out of 407 charters3 DID NOT MEET the ASBCS Financial Performance Recommendations. An additional 90 DID NOT MEET the Cash Flow standard. Cash Flow, as any business owner can assert, is a canary in the coal mine. It is a red flag indicative of financial issues. The third report to be released by the end of the year will be an in depth look at teacher compensation, benefits and issues related to travel costs for school personnel which, in many cases, exceed what much larger public districts expends for the same item. The findings in this series of policy reports exposes that, in fact, school choice is an illusion in Arizona in the absence of access to transparent and consistent information regarding charter school finances, executive compensation, contractual obligations and academic performance. In the current state of play, charter schools are not required to operate at a level of financial accountability and transparency that is as comparably stringent as is demanded of public district schools. While information in these policy reports may be alarming, none of it, under Arizona state law, is presently illegal. It is not the intent of these reports to suggest any charter operator is currently violating state law. The identified practices are all legal under the current rules. The law’s silence on these issues is deafening.

1 Family members such as brothers, sisters, spouses, ancestors and lineal descendants. The charter holder names listed were researched to discern whether the listed charter holders were related. I.e. cases where the husband and wife had different last names. (Step-parents, uncles, in-laws, cousins, nephews and ex-spouses are not considered related in these reports.) A related party corporation or partnership is one where more than 50% of the stock or more than 50% of the capital interest is owned by the taxpayer who owns the corporation or partnership. In all of the charters reviewed the charter holder held 100% of the stock. Most cases noted in this study were 100% held by a related party.

2 Distributions are amounts paid to stockholders in a “for profit” charter company. The distributions reported here come from companies that are registered as for profit charters. This is not to be confused with “for profit subsidiaries of nonprofit charters”. Distributions at those for profit subsidiaries are not visible to the public. Their audits are not public. It is assumed that the money for distributions in excess of the company’s NET are being taken from Owner’s Equity.

3 The number 407 includes all non-district, municipality, and university charters. Charter school organizations can use consolidated audits which means organizations with multiple charters can submit one audited report. This practice is detailed in these reports.

Findings and Recommendations

Topics in the First Policy Report

- Related Party Transactions and their Effect on the Marketplace

- Percentage of Related Party Expenditures to Overall Expenditures

- Checking on the validity of claims that Related Party Expenditures are Cost Effective and Efficient Transactions

- Relationships between the Corporate Boards and Charter Holders

i. Related Parties Defined and Listed

- Amounts involved in Related Party “for Profits” associated with nonprofit charters: An analysis of the financial transactions involved in these subsidiaries.

- Executive and Administrative Compensation

- Analysis of the decision making systems regarding compensation

- Comparing the declared method4 used to determine compensation alignment with similar sized organizations

- Comparisons to the competition’s (districts) compensation of superintendents in similar sized districts

- For Profit Distributions and Owners’ Equity

- Analysis of the equitable distribution of profits as they relate to:

- Net for the Year

- The Expenditures for the year

- Underfunding and depleting of the stock holder’s owners’ equity5.

- Classroom Expenditures in Charters and Districts

- Following the money used to educate our children

- Comparing and contrasting district and charter expenses in the Classroom

- Academic Performance

- Grading Schools for Traditional and Alternative Charters

- Studies comparing similar students in Charters and Districts

- Reconciling Inconsistent Financials

- Examples of inconsistent reporting on state financial reports compared to audits

- The reporting of Administrative costs on the AFRs, audits, IRS 990s with an eye towards disparities in those

4 The declared method is the stated (on the audit and to IRS) method used to determine these compensation levels. By comparing schools of 350 to compensation at districts exceeding 20,000 the charter holder “justifies” their claim to a salary that is inconsistent with the business’ size. 5 Owners’ Equity is an auditing term used in the balance sheets of for profit companies.  Finding: Related-party dealings are the modus operandi of three-fourths of the charters evaluated. While these transactions can offer cost savings to charter schools they are often used for self-enrichment. Ninety-five percent of charters have sought and received permission to bypass regulations public district schools must follow regarding related-party transactions and open bidding processes. More than 77% of charter schools conduct business with related parties–companies that employ a family member of the charter holder, or the charter holder him or herself. In addition, the boards at these subsidiary for-profit companies are often the same individuals that are on the charter’scorporate board. The corporate boards are appointed. This is the polar opposite of a public school board where the open seats are filled with elected members from the community. Arizona law allows the following configuration of charter holders and corporate boards (ARS §15-181 to §15-189):

Finding: Related-party dealings are the modus operandi of three-fourths of the charters evaluated. While these transactions can offer cost savings to charter schools they are often used for self-enrichment. Ninety-five percent of charters have sought and received permission to bypass regulations public district schools must follow regarding related-party transactions and open bidding processes. More than 77% of charter schools conduct business with related parties–companies that employ a family member of the charter holder, or the charter holder him or herself. In addition, the boards at these subsidiary for-profit companies are often the same individuals that are on the charter’scorporate board. The corporate boards are appointed. This is the polar opposite of a public school board where the open seats are filled with elected members from the community. Arizona law allows the following configuration of charter holders and corporate boards (ARS §15-181 to §15-189):

- Corporate Boards that are composed of one person, the charter

- Corporate Boards that are composed of two people, husband and wife who also hold the

- Corporate Boards that are composed of two charter holder

- Corporate Boards filled with relatives and owners of related party

- Corporate Boards where the charter holder is the board chair /

- Corporate Boards and charter holders that do not reside in

- Corporate Boards that are the same for related-party subsidiaries dealing with the non-profit charter. Salaries, bonuses and distributions from these subsidiaries are not reported on the Audits. Money moving to the subsidiaries is noted in the Related-Party section of the

o Related-Party Transactions that were present on the Audit were not always included in IRS Form 990 for the same firm. This financial and governance issue manifests as:

- Leases with a related for-profit subsidiary or individual

- Renting from a for-profit subsidiary or individual

- Purchasing goods and services from a related for-profit subsidiary or individual

- Leasing employees from a related party for-profit subsidiary or individual

- Loans and notes to a related-party for-profit subsidiary or individual

- Paying a related party for “board” services on the corporate board

- Consulting contracts to a related party, and a host of other dealings with parties related to the owners of the

- Multiple related-parties on the

Most cases indicate excessive compensation in transactions with related-parties. When the owner configurations combine with a lack of independent oversight, most charters analyzed are making decisions that are not necessarily in the educational interests of children, but are to the owner’s self-benefit. Related Parties Defined: Family members such as brothers, sisters, spouses, ancestors and lineal descendants. The charter holder names listed were researched to discern whether the listed charter holders were related. I.e. cases where the husband and wife had different last names. (Step-parents, uncles, in-laws, cousins, nephews and ex- spouses are not considered related in these reports.) A corporation or partnership in which more than 50% of the stock or more than 50% of the capital interest is owned by the taxpayer. Most cases noted in this study were 100% held by a related party. Recommendations: 1. Charters need to be held to the same public bidding procurement process as public district schools. This adaptation will make any related-party contracts public information. If compliance creates an administrative burden on the charter, then the ASBCS should facilitate and oversee the bidding process and create the opportunity for charter schools with similar needs to benefit from a combined bid process.

- Related-party employment compensation needs to be disclosed in audits and the charter must provide a market-based analysis to the ASBCS that demonstrates no more than fair-market value is paid for any compensation to related-parties. The amount of related-party employment compensation for each charter will be available to the public at the ASBCS’ website, including any documentation.

Finding: Administrative Compensation is often excessive and given other organizational ways of funneling money, these figures may understate the full compensation package owners provide for themselves. For-profit charters and for-profit related organizations do not disclose compensation, i.e. the data is not provided in the audits. Charter school operations frequently have only a few hundred students. Among public school districts with 600-1,200 students, the average superintendent compensation is $105,000. Focusing on the top half of these districts in terms of compensation per pupil, the compensation comes out to $150 per pupil. Superintendent salaries for the top paying public school districts with 600-1,200 students ranged from $101,000 to $125,000 with one outlier at $235,000. Examining charters that disclose administrative and executive salaries on their IRS Form 990 one finds a key reason why charters have more than twice the administrative expenses per student as public district schools (many charters do not disclose this information on their IRS 990, an issue6). Many charters pay administrators and charter holders far more than what equivalent personnel would receive in public district schools. There are charters (23% of the total) that have reasonable compensation packages based on the charter’s size. There are members of this group that take LESS compensation than they are due because of the financial position of the company. One particularly high compensation example is at Crown Charter School, Inc., where the top two executives paid themselves a total of half a million dollars in FY 2014. This compensation occurred even though the school had just over 250 students. Nearly $2,000 from taxpayers per student from the Arizona State General Fund went to these two individuals. By contrast, the superintendent of Scottsdale Unified made $203,000 in 2014-2015. This compensation package was in a district that is nearly 100 times larger (almost 25,000 students). Additional irregularities regarding how Crown organizes itself financially is found in the Reconciling Inconsistent Financial portion of the report. The organization has significant discrepancies between their audit and their AFRs filed with the state.

In addition none of the compensation that a charter holder is receiving from a subsidiary “for profit” is available.

- the information is not part of the audits or IRS 990, only the payments TO these organizations are visible on the audits.

The George Gervin charter with 90 students currently receives failing academic marks from the Arizona State Board of Charter Schools, yet its top paid executive, Barbara Hawkins, who also oversees a Youth Center, received $192,000 in 2013-2014. The principal of the school appears as a related-party, Nathan Hawkins, though his salary is not disclosed in the charter’s IRS 990 report. More typical examples of high compensation include Cynthia and Keith Johnson who collectively earned $317,000 for 374 students at Acorn Montessori charter school in 2013- 2014 and Brad and Deanne Tobin who collectively earned $239,000 for 126 students at Challenger Basic School. These compensation levels far surpass public district schools. For instance, the superintendent of Williams Unified School District (618 students) earned $101,000 in 2014-2015. Consequently, the top two administrators in Williams Unified earned less than $200,000. While charters may argue that despite their small size, administrators have broad and important responsibilities, the best way to address that would be to benchmark salaries to slightly larger public district schools. Recommendations: 1. Audits of charter schools need to include review of compensation to non-instructional personnel in an administrative, governance or ownership capacity. Compensation should be benchmarked by similar personnel in public school districts with less than 1,000 students for small charters with less than 600 students. For charters with more students, the benchmark threshold should be set no higher than 50% above the total number of students enrolled in the charter. The audit should provide sufficient documentation to justify the total compensation received. This analysis needs to consider ALL methods that ownership and administrators use to compensate themselves including any for-profit subsidiaries.

- Likewise, any non-instructional personnel employed by the for- profit arm of a charter operation and paid for with public funds needs to have costs fully broken down in the audit, including all salary, benefit, and consulting services with a market-based justification for the

- Charter school financial data needs to be shared with and monitored by the Auditor General’s Office just as they are for public district

Finding: Questionable (Excessive) distributions to shareholders occurred in 2014-2015 with one-third of for-profit charters. Most charter holders are nonprofits. They may have “for profit” related organization that they contract with, but the charter itself is a nonprofit. Twenty-five charter holders in Arizona are for profit corporations. As a “for profi”, they can make distributions to their shareholders. This section focuses on these 25 charter holders. In normal business practice in a free market, shareholder or partner-owned businesses do not distribute dividends (distributions in charter parlance) on shares in losing years. The money goes into retained earnings instead (or comes out of retained earnings in a bad year). Eight of the 25 for profit charter schools, including three separately incorporated parts of Pinnacle Education, engage in questionable distributions to shareholders. Six for-profit entities take out more than 10% of state revenue as profit, ranging from 12% to 45% in 2014-2015. Four of the eight take out so much for distributions that it exceeds their net profit and makes the entire entity run at a net loss, including American Basic Schools, LLC, which despite net revenues of only $66,000 in 2014-2015, distributed $422,000 to shareholders. It is assumed the money beyond the net on the year is coming from owners’quity. Excessive distributions undermine the financial stability of a charter school, which is not in the interest of taxpayers or students. Over the past 25 years, the Standard and Poor 500 reported average net profit margin after all expenses never exceeded 10%. Net profits can be retained as a source of future investment or redistributed to owners. For profit charters distributing more than 10% of revenues to owners or pushing an operating surplus into a loss are not acting as good stewards of taxpayer funds.

Recommendations: The ASBCS should be monitoring and approving any distributions in excess of the charter’s net for the year. Documentation on where the funding for the distribution came from needs to be include in the audit information. Draws on Owner’s Equity for distributions need to evaluated and checked against the company’s fiscal position on the ASBCS’ Financial Performance Recommendations.

Finding: While public district schools in 2014-2015 put 51.5% of resources directly into the classroom, charters only average 47.5%. While most executives and top administrators in the charter sector receive excessive compensation compared to their public district school counterparts, teachers in charters on average are paid more than 20% less than district teachers often without any retirement benefit (to be detailed in the third policy report). Consequently, charters put less resources into the classroom, and more into compensating those who own or operate the charter. In 2013-2014, the Auditor General reported public district schools as devoting 52% of all spending in the classroom. In contrast, charters only put 45% as found in the Annual Report of the Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction. At the end of Fiscal Year 2015 the numbers were 51.5% for District Classroom Spending7Â and 47.5% for Charter Classroom Spending. Student Support Levels at Charters was 4.9% to Districts at 7.9%. Ten years of data show that this disparity in classroom spending is a trend. However, because the Auditor General only does an annual report on public district schools, they are the only ones publicly made accountable for the distribution of their spending in the areas monitored8. (Davenport, 2016 #1179) Recommendation: Charter school financial data needs to be shared with and monitored by the Auditor General’s Office just as it is for public district schools.

7 This change in classroom spending triggered a call for a report on District Spending on Classrooms Expenses, charter spending on classrooms or classroom support accounts was NOT part of the report. 8 The report provides data on Classroom Spending (instruction), Classroom Supplies, Administration, Student Support, and Other Support. The report is only as accurate as the data provided by the charters on their Annual Financial Reviews (pgs. 2, 7 and 10).

Finding: The charter sector as a whole underperforms academically relative to similar demographic students in public district schools. On line charters show particularly poor academic performance. While some of Arizona’s college-prep charters focusing on attracting high-achieving students with a rigorous curriculum have gotten significant attention in the media, two independent studies using student-level data have found the charter sector as a whole for similar demographic students underperforms relative to the public district schools. The studies were by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) out of Stanford University and by the Brookings Institution at the behest of the Goldwater Institute. While as with public district schools, some charters certainly perform better, the overall results suggest school choice, as presently designed, is not functioning as well as it could or, based on CREDO’s results, as well as in other states. This means presently for academic-achievement for most students, school choice is leading to sub-optimal outcomes. In addition, within the charter sector, the most abysmal performance for demographically equivalent students is found with the online charters, a pattern which holds nationwide. Recommendations: Improved financial oversight as outlined in this report and improved financial transparency for the public, including parents, would enable parents to make more informed choices regarding their child’s education and make charters more accountable to taxpayers. In addition, all online charters should be reviewed immediately to evaluate the quality of their academic offerings and student achievement to determine whether their charter should continue.

Finding: Frequently numbers AFRs, Audits, and IRS filings are inconsistent even though they cover the same period. Some audits are inadequately detailed and done by out-of-state firms that may not be familiar with Arizona law. Charter schools submit AFRs to the Arizona Dept. of Education, audits to the ASBCS for the state of Arizona, and if a nonprofit, as most are, a Form 990 to the IRS. Currently while financial reports and audits are submitted annually, they are not scrutinized for consistency even though they cover the same reporting period. Audits don’t always follow a standardized format. Some auditors are in state and do good detailed work, and other audits are completed by out of state entities and may lack detail. The level of detail varies by auditor. Identifying what’s going on at particular charter sites can be challenging due to consolidated audits or, if the charter is operating in the context of a much larger nonprofit, the consolidated audit inhibits the ability to examine the charter performance more carefully. As these funds are from state taxpayer dollars, the public accounting should be consistent across all reporting forms and when it’s not, clear steps advanced to remedy deficiencies. The excuse that no one checks the accuracy of AFRs to the state and compares that data to the audits submitted to the ASBCS is an indictment of oversight. As will be detailed in subsequent reports and listed in this report’s Appendix, large numbers of charter operations are running deficits and many have negative net assets. The state needs to be ahead of potential financial problems, so they can appropriately intercede for the best interest of students and taxpayers.

Recommendations: 1. Audits need to follow a standard format that requires detail and supporting information on assets and liabilities, revenues and expenditures, and related-party expenses.

- Audits need to be done by auditors with offices located in Arizona with a demonstrated expertise in Arizona

- The ASBCS needs to provide a list of acceptable auditors using data gleaned from the audits to determine which auditors are currently providing acceptable levels of information.

- Audits need to be done for each charter entity or for the charter separate from any larger entity it might be part of THEN a Consolidated Audit can be prepared collating that data.

- Audit reports need to be numerically identical to what is provided in Federal 990s and AFRs. Any inconsistencies would need to be explained in the audit with specific plans on how to remedy the deficiency in the future.

Summary of Findings and Recommendations

| Finding |

Recommendation |

|

For three-fourths of charters, related-party transactions appear to be more for self- enrichment than saving money or benefitting students

.1. Charters need to be held to the same public bidding procurement process as public district schools. That will make any related-party contracts public information. If compliance creates an administrative burden on the charter, then the ASBCS should facilitate the bidding for them as schools have similar needs for which they would need to procure bids.

2. Any and all Related-party employment compensation needs to be disclosed in audits and the charter must provide a market-based analysis to the ASBCS that demonstrates no more than fair-market value is paid for any compensation to related-parties. The amount of related- party employment compensation for each charter will be available to the public at the ASBCS website, including any documentation

Administrative Compensation is excessive and given other organizational ways of funneling money, these figures may understate full compensation. For-profit charters do not disclose compensation and for- profit related organizations do not disclose compensation.

1. Audits need to include compensation to non-instructional personnel in an administrative or ownership capacity. Compensation should be bench-marked by similar personnel in public school districts with less than 1,000 students for small charters with less than 600 students. For charters with more students, the benchmark threshold should be set no higher than 50% above the total number of students enrolled in the charter. The audit should provide sufficient documentation to justify the total compensation received. This analysis needs to consider ALL methods that ownership and administrators use to compensate themselves including in for- profit subsidiaries.

2. Likewise, any non-instructional personnel that are technically employed by the for- profit arm of a charter operation needs to

| Finding |

Recommendation |

| High Executive Salaries Continued |

have costs fully broken down in the audit, including all salary, benefit, and consulting services with a market-based justification for the costs. |

3. Charter school financial data needs to be shared with and monitored by the Auditor General’s Office just as they are for public district schools. Questionable (excessive) distributions to shareholders occurred in 2014-2015 with by one-third of for-profit charters.The ASBCS should be monitoring and approving any distributions in excess of the charter’s net for the year. Documentation on where the funding for the distribution came from needs to be include in the audit information. Draws on Owner’s Equity for distributions need to be evaluated against the company’s fiscal position on the ASBCS’ Financial Performance Recommendations. . While public district schools in 2014-2015 put 51.5% of resources directly into the classroom, charters only average 47.5%. The prior year 2013-2014 districts spent 52% of resources directly into the classroom, charters only average 45%.Charter school financial data needs to be shared with and monitored by the Auditor General’s Office just as they are for public district schools.

| Finding |

Recommendation |

|

The charter sector as a whole underperforms academically relative to similar demographic students in public district schools. Online charters show particularly poor academic performance.

Improved financial oversight as outlined in this report and improved financial transparency for the public, including parents, would enable parents to make more informed choices regarding their child’s education and make charters more accountable to taxpayers. In addition, all online charters should be reviewed immediately to evaluate the quality of their academic offerings and student achievement to determine whether their charter should continue.

Frequently numbers in AFRs, Audits, and IRS filings are inconsistent even though they cover the same period. Some Audits are inadequately detailed and done by out-of- state firms that may not be familiar with Arizona law.

1. Audits need to follow a standard format that requires detail and supporting information on assets and liabilities, revenues and expenditures, and related- party expenses.

a. Audits need to be done by auditors with offices located in Arizona with a demonstrated expertise in Arizona law.

b. The ASBCS needs to provide a list of acceptable auditors using data gleaned from the audits to determine which auditors are currently providing acceptable levels of information.

c. Audits need to be done for each charter entity or for the charter separate from any larger entity it might be part of THEN a Consolidated Audit can be prepared collating that data.

2. Audit reports need to be numerically identical to what is provided in Federal 990s and AFRs. Any inconsistencies would need to be explained in the audit with specific plans on how to remedy the deficiency in the future.

For the rest of the report, please go to the download tab.

Charter Schools

Charter Schools