Blog

Blog

How Scary is Medicare for All? The Realistic Medicare for All Option

October 31, 2019Summary

The Grand Canyon Institute (GCI) takes the fright out of Medicare for All. This blog puts forward an illustrative Medicare for All plan that costs up to $1.3 trillion and is paid for by a payroll tax for those opting in at a rate of 10.5 percent for employers and 3.5 percent for employees. It would be modeled on the current Medicare system, which includes supplementary and complementary roles for private insurance companies.

Introduction

This Halloween, Medicare for All is one of the scariest things on the landscape for some. In reality, it’s not as simple as proponents claim, and it’s also not as scary either.

Voters are being presented with a variety of plans while the media is emphasizing cost with very little attention given to systemic analysis. In fact, the GCI’s informal polling discovered that most people not currently using Medicare are not very familiar with how it works.

This blog provides a brief overview of the health care plans proposed by leading Democratic candidates, discusses the current Medicare program, and then illustrates a Medicare for All Plan modeled after existing Medicare.

Summary

The Grand Canyon Institute (GCI) takes the fright out of Medicare for All. This blog puts forward an illustrative Medicare for All plan that costs up to $1.3 trillion and is paid for by a payroll tax for those opting in at a rate of 10.5 percent for employers and 3.5 percent for employees. It would be modeled on the current Medicare system, which includes supplementary and complementary roles for private insurance companies.

Introduction

This Halloween, Medicare for All is one of the scariest things on the landscape for some. In reality, it’s not as simple as proponents claim, and it’s also not as scary either.

Voters are being presented with a variety of plans while the media is emphasizing cost with very little attention given to systemic analysis. In fact, the GCI’s informal polling discovered that most people not currently using Medicare are not very familiar with how it works.

This blog provides a brief overview of the health care plans proposed by leading Democratic candidates, discusses the current Medicare program, and then illustrates a Medicare for All Plan modeled after existing Medicare.

Current Medicare for All and Public Option Plans Offered

Presidential candidate and Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren, who advocates a single payer Medicare for All vision for universal coverage has been purposely evasive on costs—trying to move the focus away from any increase in taxes to how much the system currently costs. Meanwhile Presidential candidate and Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, who likes to note in debates the he wrote the Medicare for All bill, has put out cost estimates that many experts have considered to be overly optimistic. Both Sanders and perhaps Warren envision a system where the government provides 100 percent of coverage at no cost to the patient with no need for private insurance.

Meanwhile, other Democratic contenders wish to add a public option. Previously, when proposed, the public option referred only to individuals purchasing insurance on the Affordable Care Act Exchanges—a relatively small number of people who cannot get insurance through their employer or other means such as qualifying for Medicaid. However, Democratic Presidential candidates such as Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg are putting forth a more robust version of a public option that would allow both individuals and employers to buy-in to Medicare. The details of their plans have often gotten lost with the focus on paying for Medicare for All.

Presidential candidate and California Senator Kamala Harris has a 10-year phase-in to a Medicare for All plan that’s similar to Sanders (Sanders has a four-year phase-in), though it would include private options like the current Medicare Advantage under Medicare Part C. She has proposed an assortment of taxes to pay for it that only hit those with incomes higher than $100,000.

One of these five candidates will likely receive the Democratic nomination (they are in the top five for polls and fundraising). Should a Democrat win the 2020 presidential election, Congress will be expected to deliver a health care plan. But plans and reality will likely differ — voters may recall that Barack Obama ran on not having an individual mandate but that ultimately became part of his signature law.

For their part, Republicans have been seeking private sector solutions that would involve less government with more transparency in billing. Republicans tend to be more comfortable with the notion that some people will not have health insurance, assuming individuals evaluate their needs relative to costs. To date, they have been content to tinker around the edges of the existing Affordable Care Act—generally, they would like to see reductions in mandated coverage and more choice—essentially enabling healthier people who are less likely to use insurance to pick plans that would cost less.

The Cost and Access Problem with the Current System

The United States spends 18 percent of GDP on health care or about $11,000 per person based on the National Health Expenditure Accounts, the official estimates of total health care spending in the United States published by the US government’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

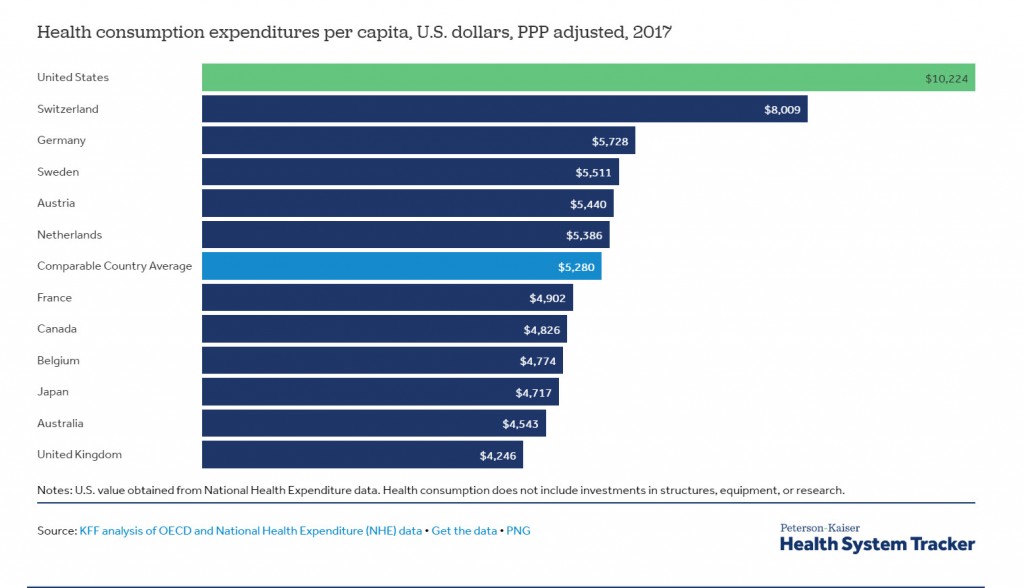

Both of those figures are projected to go up without systemic change. Overall, the U.S. spends about twice what other developed countries do on health care both as a percent of GDP and based on purchasing power parity (see Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1

The Kaiser Family Foundation 2019 Employer Health Benefits survey found a continuing rise in the portion employees pay for family health insurance coverage (excluding deductible), which has reached $6,015 annually (see Figure A in report). The employer share now reaches $14,000. For single coverage premiums, employees now pay about $1,250, while employers pay $6,000 (see Figure B in report). While the vast majority of private sector workers are offered health insurance through their employer, overall only 6 in 10 firms offer health insurance, with smaller firms primarily not providing it. Health benefits are almost universal among firms employing 200 or more (see Figure G in report).

Some of the challenges with the current system include:

- A high and growing cost burden on employers. Aggregate private insurance costs continue to rise faster than total Medicare spending even though we have an aging population. These high costs also reduce the growth of wages and salaries. The cost of providing health care also puts US businesses at a disadvantage internationally in terms of competing with foreign businesses that do not carry this cost burden.

- High-deductible plans. Many families find that their employer-provided health insurance plans have such high deductibles that it can be too expensive to use.

- Subsidy gap for middle-income earners. People, not covered by an employer, with incomes more than 400 percent above the poverty line (above $49,960 for a single individual, $85,340 for family of three) do not qualify for subsidies to purchase health insurance from the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Exchanges. As a result, they are trapped with high-cost plans with very high deductibles in part because the risk-pools for these plans have too many heavy health care users that drive up costs.

- Employer-based coverage undermines workforce mobility. Health insurance can be prohibitively expensive and therefore a deterrent if an individual wishes to seek new employment or explore her own business venture. New, smaller firms have a harder time competing for talent because they cannot compete on health benefits. Likewise, employer-based health care may contribute to discrimination against employing older workers, who are more likely to use health benefits.

- Finally, many people who would benefit from having health insurance aren’t covered. Collectively, about 10 percent of the nonelderly population lack health insurance and others underutilize their coverage due to high deductibles.

This landscape leads to the call for health care reform, with the Democratic Presidential campaign bringing a focus on Medicare for All. Polls show more than 6 in 10 Americans support Medicare for All conceptually.

How Medicare Works

Until people approach 65, few give much thought to Medicare, other than acknowledging that Social Security and Medicare are paid through an employer-matched FICA tax of 7.65 percent, 6.2 percent to fund Social Security and 1.45 percent to fund Medicare.[1]

Medicare while publicly funded, does not cover all expenses, so it still enables opportunities for private insurance. Generally, Medicare covers about 80 percent of anticipated health care costs with premiums, deductibles, co-pays and cost-sharing covering the rest. Coverage is divided into ‘parts.’

Medicare Part A and Part B are known as ‘Original Medicare’ where participants access health care on a fee-for-service basis. Medicare Part A covers hospitalization with a deductible of almost $1,500 and significant cost-sharing after 60 days. Medicare Part B covers outpatient services and has a monthly premium of about $140 and an annual deductible of about $200. Individuals are then responsible for 20 percent of the cost of health care with Medicare covering the rest. Together the deductibles for Part A and Part B total about $1,600 annually.

To fill the gaps of Original Medicare, participants can purchase Medicare Supplemental Insurance known as Medigap. These policies are sold by private insurers and help cover the costs associated with Medicare Parts A and B including copayments, coinsurance and deductibles. Medigap premiums cost around $150 per month-but keep in mind these are prices to cover seniors.

Medicare Part C is a public-private partnership known as Medicare Advantage and covers services included in Parts A and B (and sometimes Part D – see below). Health care is provided by health insurance companies at lower prices by restricting provider options through HMO or PPO network-based plans. Medicare Advantage plans average about $23 per person monthly and offer lower out-of-pocket costs than Original Medicare.

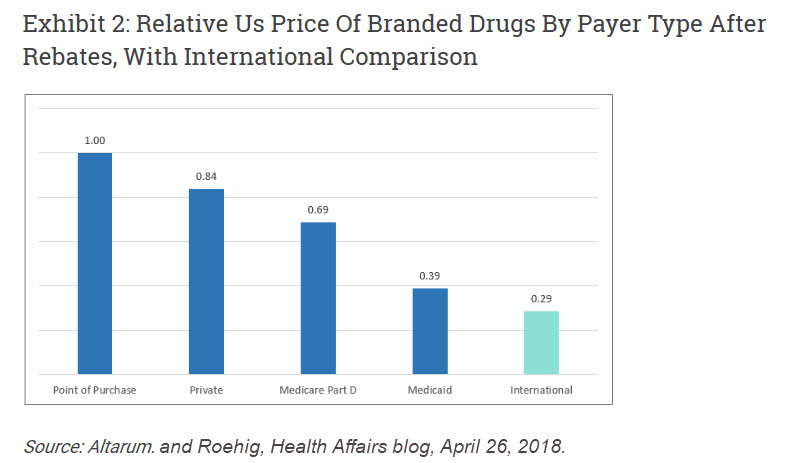

Medicare Part D covers prescription drugs and is provided by private insurance companies with subsidies from the federal government. Under any reform, Medicare would likely be granted the ability to negotiate drug payments, an important change that would likely drive prescription prices down. The revised Medicare Part D would include co-payments and no deductible with likely a limit on overall out-of-pocket expense. Presently RAND cites research that estimates Medicare through government regulation combined with private insurers obtains better rebates than private insurance, so drug prices are about 80 percent of private insurance. Medicaid requires a “best price” rule, meaning manufacturers must sell to Medicaid at the lowest price offered anyone else, but some drugs included with Medicare are excluded in the Medicaid formulary (see Exhibit 2). RAND presumes that without limiting formularies or other measures to restrict drug costs, Medicare’s costs could be reduced by an additional 10 percent if the government had enhanced negotiating power. That’s conservative compared to what some analysts suggest and would still exceed Medicaid’s prices.

The Grand Canyon Institute’s Illustrative Medicare for All Plan

GCI’s analysis presents a Medicare for All plan that is both comprehensive and realistic. It expands access to Medicare plans to individuals and employers with coverage for about 80 percent of an insured person’s anticipated health care costs, including the option to enroll at slightly higher costs in a Medicare Advantage plan that provides more complete coverage. It requires everyone to either sign up for Medicare or purchase a private insurance plan with similar coverage. Current Medicaid and Affordable Care Act dollars are reallocated to assist low-income households, most of the self-employed, and small businesses, which lowers their costs. To ensure comparability with the current employer-based system it is paid for by a 14 percent payroll tax, with a cost share of 10.5 percent from employers and 3.5 percent by employees for those that opt in. Employers, not opting in, are required to provide a private plan that meets the 80 percent coverage threshold.

This plan represents a realistic hybrid of all the Democratic proposals. Based on research studies evaluating Medicare for All, it presumes that this kind of universal coverage can be achieved by paying no more than what is currently spent on private insurance. As with Medicare, private insurance supplements similar to Medigap could be purchased by households to cover all or part of the 20 percent of anticipated costs not covered by Medicare. Consequently, out-of-pocket expenses should decline. This hybrid plan is somewhat more encompassing than what has been offered by Presidential candidates Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg. But as it retains deductibles, co-payments, and limits on coverage, is less encompassing than plans put forward or implied by candidates Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Kamala Harris. Importantly, this plan leads to universal coverage.

GCI’s illustrative plan includes the following three components.

Component 1: Making Existing Medicare Available to All

Pragmatically, free universal health care (100 percent coverage plan) is unlikely to pass Congress if a Democrat is elected President in 2020. Even the single payer system in Canada has a private insurance supplement.

Medicare for All would force changes among health care providers, and they will certainly use their financial resources to make sure that is known (i.e., scare you). In fact, they already are. The Partnership for America’s Health Care Future is a well-funded, industry-based effort to protect themselves from the likely cuts to provider rates with any expansion of Medicare, including the public option. To address their primary concern, the GCI hybrid Medicare for All model assumes Medicare Hospital reimbursement rates increase 15 percent, and going forward restrictions on the growth of Medicare rates under the Affordable Care Act are likely to be relaxed.

Based on GCI’s calculations the hybrid Medicare for All plan could likely be funded with a 10.5 percent payroll tax on employers with a 3.5 percent payroll tax on employees. Plans would cover 80 percent of anticipated health care costs with deductibles limited to no more than the $1,600 per person and $3,2000 per family. Private plans would need to comply with this overall structure to facilitate comparisons. The current Medicare Plan B monthly insurance premium would be replaced by the payroll tax.

Medicare for All would also include additional private insurance options. The cost depends on the plan choice and a person’s age (individuals closer to 65 pay more). Those under 65 use about one-third as much health care per person as those on Medicare.[2] Medigap-style supplemental insurance would help users pay for expenses not covered by Parts A and B (i.e., deductibles, co-insurance). As a typical Medicare supplement now costs about $150 per month, an expanded Medicare system would accommodate supplemental plans that would likely average around $50 per month for individuals under 65 or $125 for families. Or users could opt for a Medicare Advantage HMO or PPO plans to provide overall lower cost coverage with restrictions on the health care providers they can access. Current Medicare Advantage premiums average $23 a month, so an expanded Medicare population would likely pay about $10 for individuals per month to $25 for families. Plans for individuals closer to 65 would be more expensive. Medicare Advantage covers all out-of-pocket costs for hospitalization and outpatient services like doctor visits.

While the coverage requirements of employer-provided insurance would increase to at least match the Medicare for All plans in terms of services—private employers would not be obliged to choose Medicare for All.

Component 2: Give employers the option of maintaining private insurance or participating in Medicare for All with a requirement that employers cover at least 60 percent of costs for employees and families and 80 percent of costs if they only subsidize the individual insurance of the employee.

Employer choice would remain, but employers would need to purchase plans that are comparable to Medicare. Employers would be required to cover 80 percent of costs at a minimum (plan covers 80 percent of actuarially estimated expected health care costs) and deductible limits are matched.

Presently, employer-sponsored coverage typically pays about 75 percent of the cost of health insurance with employees paying the remaining 25 percent (individuals receive slightly higher coverage than families). Therefore, an employer would need to cover on average 60 percent of anticipated health care costs for a family coverage. With an 80-20 plan, the employer would pay 60 percent of the plan’s cost, the employee would cover 20 percent, and the remaining 20 percent not covered by the plan would also be an expense falling on the employee based on health care utilization. That’s assuming the employer was also helping to provide family coverage.

If an employer wished to offer a 60-40 plan, then the employer would need to cover the full cost of the plan, since the remaining cost, not covered by insurance, would fall on the employee.

Smaller employers are more likely to subsidize the cost of an employee but not her family. In that case, the employer might be required to pay at least 80 percent of an employee’s anticipated health costs, in other words the full premium in an 80-20 plan. To improve access and reduce complexity, an additional requirement for employer plans is that the deductible could not exceed the Medicare for All deductible cumulatively across Parts A and B (about $1,600). That deductible is per person and there would need to be a total family cap of likely no more than two times that amount ($3,200) which roughly comports with existing practice in private insurance.

When an employer provides coverage, then the Medicare for All payroll tax does not apply.

If an employee’s firm did not subsidize family coverage, an employee wishing to cover dependents would need to then decide whether to opt-in to a Medicare for All plan for them or pay whatever the private insurance cost is available through their employer. If she chose Medicare for All for dependent coverage, then she would need to contribute the employee portion (3.5 percent) of the payroll tax portion of Medicare for All, but the employer would not be required to contribute.

Component 3: Payroll Tax to replace private insurance premiums for Medicare for All Option

The most logical replacement for employer-subsidized insurance premiums would be a payroll tax. Larger employers who currently compete in part on the basis of their benefit package are going to be somewhat less likely to opt-in to Medicare for All initially, though many would choose Medicare for All and also subsidize the cost of Medicare supplements for their employees. Small- and medium-sized employers will likely find Medicare for All as similar or lower cost. Employers not presently offering health insurance would see a cost increase.

In 2019, private health insurance premium expenditures in the United States are projected to amount to $1.3 trillion — that’s about $950 billion from employers and $350 billion from employees or those self-employed.[3]

Across all civilian workers, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that insurance (almost entirely health insurance) is about 11.1 percent of payroll.[4]. GDP statistics indicate that total payrolls appear to be $9.4 trillion.

So what kind of payroll tax generates $1.3 trillion dollars on $9.4 trillion? 14 percent. If that is divided between employer and employee on a 3 to 1 ratio (75 percent to 25 percent), then Medicare for All premiums would be paid with a 10.5 percent payroll tax on employers and 3.5 percent payroll tax on employees.

The survey data of existing employer health care costs indicates that for many employers this would be a reduction in costs. For those experiencing an increase in costs, the change in the requirements of what they have to offer (no more high-deductible plans), this would likely provide them sufficient incentive to move to a Medicare for All plan. But in many cases because they no longer have to deal with small risk pools, their costs may not change substantially or go down.

Small employers with revenues less than $3 million—many of whom don’t offer health insurance or are stressed financially — could be partly shielded with a sliding-scale reduction in the 10.5 percent employer payroll tax. Likewise, a sliding-scale reduction in payments could be applied for the self-employed or independent contractors to cover those with middle and lower incomes, as they would have to otherwise cover the full 14 percent. This would apply to incomes under 500 percent of the poverty line (i.e., $62,450 for an individual and $106,650 for a family of three).

Because Medicare pays reimbursement rates much lower than private insurance, medical delivery services, especially hospitals, would need to adapt. While the claim that Medicare for All would force mass closures of hospitals has been found to be insufficiently substantiated by news organizations, Medicare rates might need to increase about 15 percent as it pertains to hospital expenses to match current hospital cost structures, though critics note that hospitals have means to reduce their own overhead as well. Even with a 15 percent increase that still would be substantially less than the private insurance rates hospitals receive that are above their costs. The 15 percent hospital rate adjustment should substantially close or eliminate the $54 billion current gap hospitals note between Medicare reimbursement and actual hospital costs. Universal coverage should also virtually eliminate all cases of uncompensated care, which currently cost hospitals $38 billion. The role of Medicaid would change, and as a consequence providers would receive the higher Medicare reimbursement rates instead of Medicaid reimbursement rates, which would also boost the bottom-line for hospitals and private providers.

The RAND Institute estimates additional administrative savings that come from the simplification and standardization in the health care system both at the insurance administration and medical provider levels (realistic Medicare for All may sound complex but it’s much simpler than the existing system). Those savings would make the 80-20 plans more affordable and enable them to expand coverage to the roughly 11 percent of working adults that currently lack health care coverage according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Existing Medicaid would provide supplements to insure people with incomes less than 133 percent of the poverty line (current Medicaid expansion cut off) on a sliding scale. In addition, Affordable Care Act Exchange subsidies could help small employers and the self-employed reduce their share of the payroll tax.

Due to the persistence of co-payments, concerns that “free” health care would lead to overuse of services, as was documented in a classic RAND study, would be mitigated. However, universal, more affordable care, would lead to wider demand—but not nearly as much as under a “free” system, thereby constraining costs.

Given the complex institutional structure of health care in the United States, this is a more realistic, less disruptive model of what Medicare for All might look like.

Conclusion

Medicare for All, the more realistic, less disruptive version, presents an opportunity to provide universal health care coverage while continuing availability of private health insurance. Importantly, expansion of the current Medicare program eliminates some of the unknowns that would result from introducing an entirely new system for providing health care insurance.

The illustrative Medicare for All plan presented in this blog would financially stress aspects of the current U.S. health care system. With its ample resources, the sector can be expected to promote its concerns about these financial pressures. However, raising Medicare rates for hospital coverage by 15 percent as well as eliminating competing lower Medicaid rates and uncompensated care should mitigate financial issues.

Benefits to the proposed Medicare for All plan include:

- Expanding upon the existing infrastructure of Medicare, which has proven to be a successful health care system.

- Funding it through a payroll tax system that is similar to how employer-based insurance is funded, which would ease the transition to universal coverage.

- Raising the bar for the minimum insurance that employers offer.

- Giving employers and individuals the option of purchasing insurance privately or choosing a Medicare for All plan based on the existing Medicare system.

- Reforming the prescription drug benefit so that Medicare has the authority to negotiate drug prices.

- Ending the problem of small risk pools, uncertainty and high expenses that smaller businesses and people on the individual market face presently.

- Offering an additional choice of private Medigap or Medicare Advantage plans to help meet the costs not covered by Original Medicare.

- Allowing for private insurance outside the Medicare framework to continue, as an instrumental component in the U.S. health care system.

Don’t be startled if Medicare for All shows up at your door on Halloween. It’s not that scary. But be prepared for those that do benefit from the health care status quo to give you quite a fright about its impact.

[1] Social Security is not paid on wage, salary or self-employment income above $132,900. Medicare has no income cap.

[2] The 2014 Medicare cost per enrollee was $10,986. The private insurance claim data for the same year was $4,974 as noted by the Health Care Cost Institute. Medicare reimbursement rates are lower than private insurance. Assuming a Medicare for All plan that had rates about 80 percent of private insurance (currently physician rates are around that and hospital rates are below that). Based on that data, costs for the general population under 65 should be about one-third that of those on Medicare.

[3] This calculation comes from two sources: The RAND Institute estimates private health insurance at about $1.3 trillion dollars. The Urban Institute under scenario 7 (page 34) notes employer paid costs at $950 billion.

[4] Calculation from Bureau of Labor Statistics Table 2: Civilian workers by occupational and industry group (June 2019). Insurance is 8.7 percent of compensation and wages and salaries with supplemental pay plus paid leave totaling 78.6 percent of total compensation, making insurance 11.1 percent of monetary compensation/payroll. The other benefits include things paid for by the employer such as employer share of FICA and retirement. This figure is higher for large employers of 500 or more who tend to offer better health insurance options, especially for families.