Unemployment

Unemployment

Impact of Losing Emergency Unemployment Compensation in Arizona

December 21, 2013On Dec. 28, 2013, Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) benefits terminated for 13,161 Arizona families. Arizona’s unemployment average weekly benefit ranks as the third lowest in the country, and is about 70 percent of our neighboring states. Nonetheless, the loss of $220 in average weekly compensation ($240 maximum) will in most cases place severe financial consequences on the long-term unemployed, leading to possibly loss of adequate housing, reliable transportation, and leading to a drawing down of savings—including often already inadequate retirement savings, or going into debt on top of the psychological burden unemployment places on people.

Studies indicate that the loss of unemployment benefits will not facilitate the movement of the long-term unemployed into jobs well, but rather a larger result will be growing numbers leaving the labor force, which will bring down the unemployment rate—but for the wrong reason.

As a consequence, the potential economic growth for the state will diminish, due to underutilized labor resources.

Policy Paper

December 31, 2013

(revised Jan. 31, 2014)

Impact of Losing Emergency Unemployment Compensation in Arizona

By Dave Wells, Ph.D.

Research Director

Executive Summary

On Dec. 28, 2013, Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) benefits terminated for 13,161 Arizona families. Arizona’s unemployment average weekly benefit ranks as the third lowest in the country, and is about 70 percent of our neighboring states. Nonetheless, the loss of $220 in average weekly compensation ($240 maximum) will in most cases place severe financial consequences on the long-term unemployed, leading to possibly loss of adequate housing, reliable transportation, and leading to a drawing down of savings—including often already inadequate retirement savings, or going into debt on top of the psychological burden unemployment places on people.

Studies indicate that the loss of unemployment benefits will not facilitate the movement of the long-term unemployed into jobs well, but rather a larger result will be growing numbers leaving the labor force, which will bring down the unemployment rate—but for the wrong reason.

As a consequence, the potential economic growth for the state will diminish, due to underutilized labor resources.

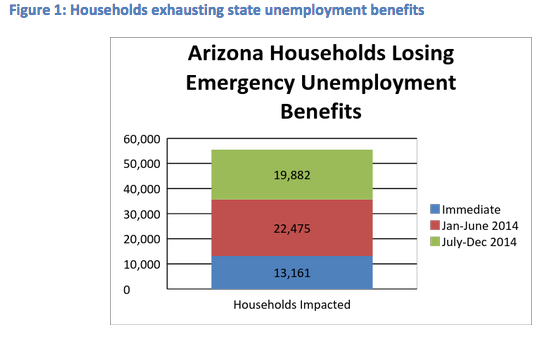

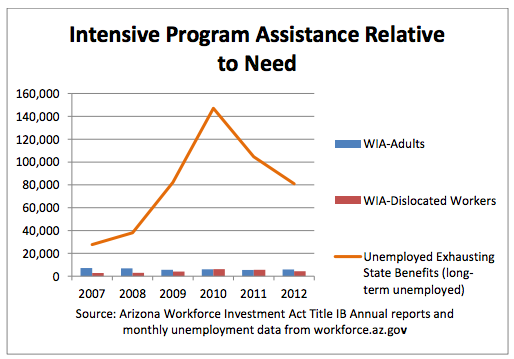

Figure 1: Households exhausting state unemployment benefits

KEY FINDINGS:

- Nationwide about 40 percent of the unemployed have been looking for a job for more than six months.

- The portion of the labor force unemployed six months or longer today is greater or equal to the highs of unemployment in any prior recession since the Great Depression.

- In Arizona the loss of extended unemployment benefits has negatively impacted 13,161 households immediately and a projected additional 42,400 households by the end of 2014, meaning 55,500 households in total will be impacted.

- The loss of extended unemployment benefits will mean a $174 million loss in income to the state that will lead to the loss of 1,600 jobs.

- Arizona’s unemployment rate has fallen to 7.8 percent in November from its high of 10.8 percent in January 2010 not due to more employment, but because 130,000 Arizonans have left the labor force.

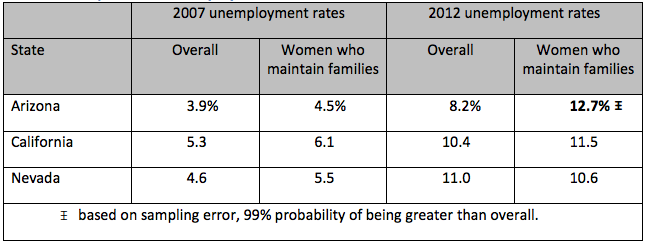

- The unemployment rate for women who maintain families (do not have a spouse present) has risen from 4.5 percent in 2007 to 12.7 percent in 2012, a higher rate for this subgroup than any state that borders Arizona, even though both California and Nevada have overall higher unemployment rates.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS:

- Congress needs to continue the gradual phase out of emergency unemployment benefits. They should not disappear overnight. At its peak workers could qualify for up to 99 weeks of unemployment benefits. In 2013, the maximum of 73 weeks required a state to have an unemployment rate of at least 9 percent. Arizona’s workers qualified for 63 weeks with 37 of them from the federal program. Moving from up to 63 weeks to 26 overnight is a drastic shock. Reliable transportation and housing security are important parts of a successful job search, which will be undermined significantly by this dramatic change.

- To address long-term unemployment and the 150,000 people who have left the labor force due to an inability to find work since 2008, Arizona needs to improve job placement and training programs to better facilitate the movement of the unemployed into worthwhile employment. Federal programs don’t sufficiently reach these people. A $24 million competitive grant program (equivalent to the financial award to Apple) to fund the best ideas would be a good place to start.

- To address the high unemployment rate of women who maintain families, the state needs to reinstate the $80 million in childcare subsidies on top of the approximately $120 million provided through the federal government. Since FY2008 the state has reduced and then eliminated its portion here and frozen enrollment into the system–this particularly harms a mother’s ability to secure and maintain employment and is likely one of the drivers of the larger unemployment rate for women who support families.

“The most pressing problem facing the United States today is not the federal budget deficit, the national debt, or excessive federal spending. It is the labor market.”

—Michael Strain, American Enterprise Institute, writing in National Review

The Unemployment Insurance System in Brief

To qualify for unemployment benefits one needs have lost his or her job through no fault of their own, as opposed to a job leaver or a new entrant or re-entrant to the labor force. In addition, the person needs to be actively searching for work. In Arizona unemployment Insurance is a benefit paid for by employers on the first $7,000 of each eligible worker’s payroll in a given year. Tax rates vary with an employer’s experience index, the number of workers they lay off who have needed benefits. When calculated as a percent of total payroll Arizona’s typical unemployment tax rate of 0.47 percent is half the national average.

Arizona’s benefits replace half a worker’s lost wages up to maximum of $240 a week. So any unemployed worker formally making more than $25,000 a year will receive less than half their lost wages. Arizona’s maximum weekly benefits are the second lowest in the country and its average benefits are the third lowest in the country. Nevada, for instance, pays out an average weekly benefit about $90 more than Arizona, and workers there can receive as much as $402 a week.

The first 26 weeks are paid through the state program, after which emergency unemployment benefits paid for by the federal government come into play. Unemployment is a lagging economic indicator, so job losses tend to pile up after the economy has already faltered and then pick up again after the rest of the economy shows signs of growth.

During times of cyclical unemployment, unemployment benefits are an automatic stabilizer helping smooth out consumption disruptions by aiding the unemployed during a time when there aren’t sufficient employment options due to cyclical conditions. When the economy experiences cyclical unemployment, the federal government frequently extends unemployment benefits beyond the initial 26 weeks. The federal payments match what the worker would have received through the state system.

Emergency Unemployment Benefits for those Unemployed more than Six Months

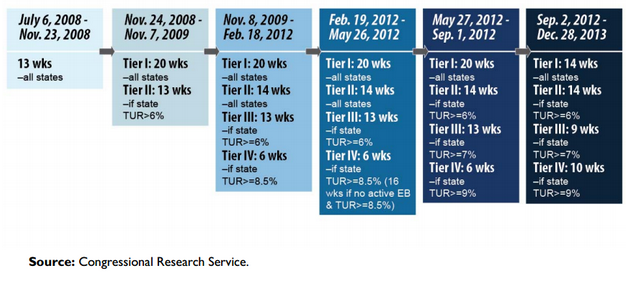

The current extensions began in July 2008 under what is called Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) which has four tiers. At the time the national unemployment rate was 5.7 percent and growing. The tiers have been adjusted with each reauthorization or expansion.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics indicates that Arizona has a 3-month seasonally adjusted total unemployment rate of 8.1 percent, so long-term unemployed workers could potentially receive up to 37 additional weeks of benefits beyond the initial 26 weeks provided by the state (tiers 1 through 3), yielding a maximum of 63 weeks of benefits under the EUC that expired on December 28, 2013.

Extended Weeks of Benefits

- Tier1 Up to 14 weeks of benefits)-all states

- Tier 2 Up to 14 more weeks in states with a 3-month seasonally adjusted total unemployment rate (TUR) of at least 6.0%

- Tier 3:Up to 9 more weeks of benefits in states with a 3-month seasonally adjusted TUR of at least 7.0%

- Tier 4 Up to more 10 weeks of benefits in states with a 3-month seasonally adjusted TUR of least 9.0%

The EUC phased in and has begun to phase out as illustrated in figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Benefits Available in Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08), July 6, 2008-December 28, 2013

POLICY RECOMMENDATION:

Congress needs to continue the gradual phase out of emergency unemployment benefits. They should not disappear overnight. At its peak workers could qualify for up to 99 weeks of unemployment benefits. In 2013, the maximum of 73 weeks required a state to have an unemployment rate of at least 9 percent. Arizona’s workers qualified for 63 weeks with 37 of them from the federal program. Moving from up to 63 weeks to 26 overnight is a drastic shock. Reliable transportation and housing security are important parts of a successful job search, which will be undermined significantly by this dramatic change.

Given that the national unemployment rate has been gradually dropping and a number of states have unemployment rates below six percent, one possible change would be to make 6 percent the requirement for tier 1, seven percent the requirement for tier 2, eight percent the requirement for tier 3 and nine percent the requirement for tier 4. In that case, Arizona’s unemployed workers would still be eligible for up to 37 additional weeks now that would drop to 28 additional weeks if the unemployment rate in Arizona remains below 8 percent.

Failing to Renew Emergency Unemployment Benefits Will Cost 1,600 Jobs

The Grand Canyon Institute expects those receiving benefits to drop by about 15 percent in 2014 and the portion of recipients exhausting benefits to decline only slightly to 45 percent. People who received their first payment in July 2013 will reach the six month end in January 2014. Using existing first payments since July and projecting out that 45 percent of them will exhaust benefits—and then presuming the 15 percent year to year decline in monthly first payments for those months beyond May yields he 54,500 impacted households in Figure 1.

Households spend nearly all of their unemployment benefits. The Grand Canyon Institute projects a slight decline in households who would be eligible for EUC in 2014 from 2013 if it were renewed, expecting 11,100 people each month. However, unemployment benefits have been shown to modestly increase the length of time people are on unemployment—for some it keeps them searching longer and in the labor market and for a few the loss of benefits speeds up their time to find a job. We estimate that 1,000 of the people each month who would be eligible for extended benefits would more quickly find a job if extended benefits were terminated, yielding 10,100 people each month at the average weekly benefit rate of $220 a week, resulting in a $116 million direct impact. The Congressional Budget Office and other leading economic forecasters use a 1.5 multiplier impact for the overall impact yielding $174 million. That increase to GDP should create a proportional increase in jobs, meaning a one percent increase in GDP would lead to a one percent increase in jobs. Using that methodology GCI estimates 1,600 jobs would be lost if that $174 million stimulus did not occur.

Of course, household spending won’t go to zero if the EUC is not extended, but households would need to pull from their own assets—such as borrowing from retirement or taking on credit card debt, meaning that to the degree the $116 million is replaced by these alternative sources of funds, those funds will diminish future consumption by an equivalent amount or more, due to the interest on credit card debt, for instance. For full details see the economic impact appendix at the end of the report.

Arizona’s Labor Market Remains Weak

The labor force has two components: those employed and those not employed but looking for work. If an unemployed worker becomes discouraged and ceases to actively look for work, then they drop out of the labor force. That’s significant as Arizona’s labor force has dropped by 150,000 during this economic turndown.

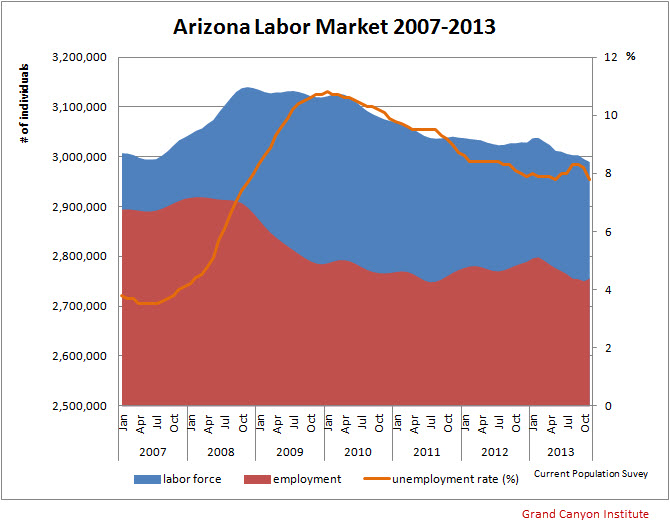

Arizona’s preliminary unemployment rate for November dropped to 7.8 percent, which if sustained represents the lowest point since November of 2008 when it was 7.7 percent. However, a closer look at the numbers illustrated in Figure 3 shows that Arizona’s unemployment rate has dropped due to people leaving the labor force, not due to people finding employment. In November 2008, the labor force in Arizona peaked at 3.14 million and the unemployment rate stood at 7.7 percent. Participation rates held steady as employment plummeted, so that by January 2010, the unemployment rate was 10.8 percent and the labor force participation rate had only dipped to 3.12 million.

Figure 3: Arizona Labor Participation, Employment and Unemployment Rate

By November 2013, Arizona labor force participation rate had dropped to 2.99 million—and with it the unemployment rate fell to 7.8 percent. The idea that employment has failed to grow in Arizona does not mesh well with the BLS monthly jobs reports which have shown growth in employment in Arizona. Arizona stands out as an anomaly in that most states, including bordering states of California, Nevada, Colorado, and Utah show growth in employment in both the BLS household survey and the BLS employer survey. Arizona results are summarized in Table 1.

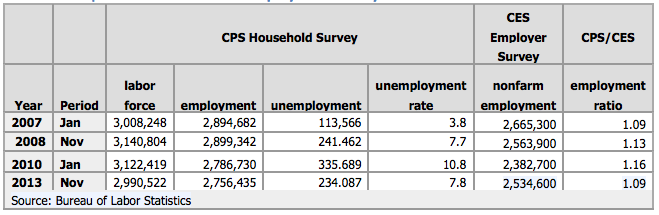

The BLS surveys 60,000 households nationwide each month to determine the unemployment rate as part of the Current Population Survey. The Current Employment Statistics (CES) surveys 145,000 employers nationwide monthly and gives more details on the employer market by sectors, though it excludes self-employment and farm employment and cannot distinguish whether some people hold multiple jobs, while others have none.

Table 1: Comparison of CPS and CES Employment Surveys

During the economic turndown informal employment and self-employment may have taken on a greater role, as from Jan. 2007 to Nov. 2008, the CPS survey shows a stagnant employment picture, while the CES Survey shows a labor market in free fall. Essentially, as workers lost positions in larger firms, they took on a more entrepreneurial approach to making ends meet, meaning their employment would only show up in the CPS survey. The November 2013 results suggest the more formal labor market has recovered, as we again see a CPS/CES employment ratio of 1.09. However, the unemployment rate is double what it was in January 2007 and we’ve lost 150,000 people from the labor market since Nov. 2008 and 130,000 since January 2010—that is nearly a five percent drop.

If November’s unemployment rate were calculated based on the labor force size in November 2008, Arizona’s unemployment rate would be 12.2 percent, suggesting November’s 7.8 percent unemployment significantly overstates the health of the employment picture.

Unemployment rates vary by subgroups. Younger adults are more likely to be unemployed than adults 55-64, for instance. However, given recent policy decisions the unemployment rate for women who maintain families stands out.

Table 2: Comparison of Unemployment Overall with Women who Maintain Families

For instance, consider Nevada and California which have had higher unemployment rates than Arizona during this economic turndown and note the comparative standing of women who maintain families in each. As shown in Table 2, in 2007 women who maintain families (no spouse present) had a slightly higher rate of unemployment across the three states as might be expected given the challenges of balancing employment and responsibility for children. However, by 2012, their situation had deteriorated to a 12.7 percent unemployment rate. These figures should be taken as approximate as the margin of error for estimating unemployment is quite large for a comparatively smaller subgroup like women who maintain families. Nonetheless, compared to years prior, 2012 for Arizona stands out as being the only case where the difference between the overall and women who maintains families rates meets statistically significance at the 99 percent level.

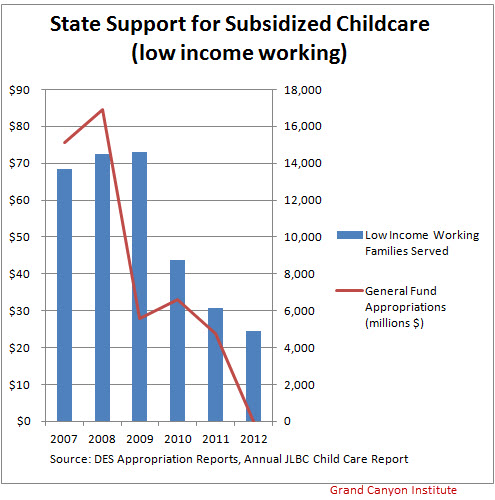

Figure 4: Arizona DES Subsidized Childcare – Low Income Working Families Served

With the elimination of state general funding for low income working parents childcare, the number of families served has plummeted by nearly 10,000 families since 2009, as federal funds have become the lone support. Federal stimulus dollars assisted 2009’s funding shortfall. As shown in Figure 4, the number of families served has dropped by two-thirds since 2007.

POLICY RECOMMENDATION:

To address the high unemployment rate of women who maintain families, the state needs to reinstate the $80 million in childcare subsidies on top of the approximately $120 million provided through the federal government that helps fund a variety of childcare services. Since FY2008 the state has reduced and then eliminated its portion here and frozen enrollment into the system–this particularly harms a mother’s ability to secure and maintain employment and is likely one of the drivers of the larger unemployment rate for women who support families.

Long-Term Unemployed Consequence of Labor Market Woes

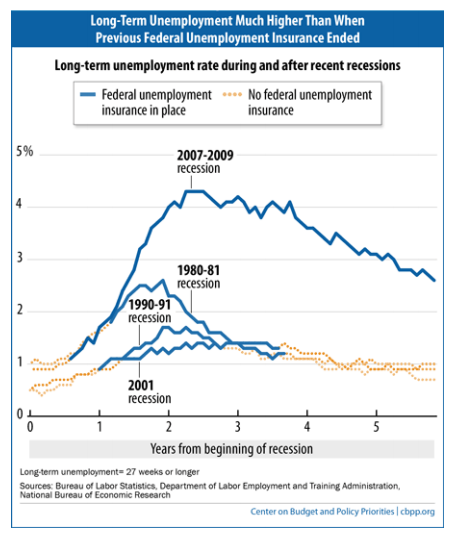

Figure 5: Long-Term Unemployment Much Higher Than Prior Recessions

Figure 5 illustrates that nationwide 2.6 percent of the labor force has been out of work for more than 6 months that matches the peak of the 1980-81 recession. As of November 2013, they represented 38 percent of those unemployed down only slightly from the 40 percent who were long-term unemployed a year earlier.

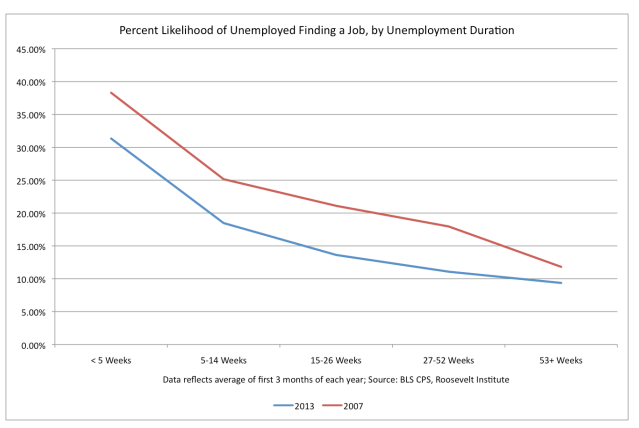

Figure 6: Percentage Distribution of Time to Find a Job for Unemployed

Figure 6 shows the state of the unemployed in 2007 and 2013. In 2007 nearly 4 in 10 unemployed workers found work within 5 weeks, but as the length of unemployment increases the likelihood of finding employment in each duration period falls. By 2013 the situation is worse, at every duration point the probability of finding employment is less, and the ultimate outcome for many are that they drop out of the labor force.

Unemployment eats away at a worker’s psyche and for good reason. Rand Ghayad, a visiting fellow at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston and doctoral candidate at Northeastern mailed out nearly 5,000 resumes which differed in experience, age and length of unemployment. He found despite better qualifications after 6 months of unemployment, applicant resumes were more likely to be rejected, suggesting that larger unemployment gaps make otherwise excellent candidates increasingly unemployable by standard screening procedures used by many employers, adding urgency to the need for quality placement and training programs.

POLICY RECOMMENDATION:

To address long-term unemployment and the 150,000 people who have left the labor force due to an inability to find work, Arizona needs to improve job placement and training programs to better facilitate the movement of the unemployed into worthwhile employment.

Begin with a pilot launch of $24 million in General Fund appropriations to better target the needs of workers who have experienced long-term unemployment or become discouraged and dropped out of the labor force.

Why $24 million? That’s how much the Arizona Commerce Authority is awarding Apple for locating a plant in Mesa that ultimately will employ 700 people—though many will likely move to Arizona to take those jobs. $10 million is a direct grant and the remaining $14 million comes from a $20,000 refundable tax credit per job created.

But why not take another $24 million and invest it in ways that improve the employability of the long-term unemployed to improve the state’s future growth?

Most federal training programs target disadvantaged youth, disadvantaged adults or adults who have lost their job due to disruptions caused by foreign trade (dislocated workers). However, those don’t match up well with the needs of the long-term unemployed workforce.

The number of potential beneficiaries is huge. Comparing the Work Force Investment Act (WIA) participants to the number of people who were receiving unemployment benefits but unable to find work after six months gives an idea of the enormity of the need, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Workers receiving WIA–Adult or WIA-Dislocated Worker Assistance Relative to Number of Workers Exhausting State Unemployment Benefits

The gap may be even larger than what’s shown in Figure 7. Keep in mind that of those unemployed, even during the depths of the recession, the number of workers receiving emergency unemployment compensation after exhausting state benefits never exceeded one in three of the unemployed, so the total unemployed population is at least three times larger. In addition, as already noted 150,000 people disappeared from the labor force from 2008 to 2013 with 130,000 of that occurring from 2010 onwards. All of this is to suggest that available worker training and placement programs fall far short of the potential demand for them.

Programs would need to come up with effective means of overcoming barriers to employment. Frequently, despite qualifications that may exceed other applicants, many employers consider being unemployed as a signal that the worker has problems and screens them out, especially after 6 months of unemployment.

In addition, long-term unemployed workers have been through a psychological battlefield of self-blame and low self-esteem and many have reached a point of expecting to be rejected. None of this helps put them in a better position to be employed. The stress can also lead to family breakups as well.

Programs aimed at the long-term unemployed could be a key asset in helping them recover their careers, and if done well, would have a strong positive return on state investment, as a more positive reintegration to work can mean thousands of dollars more in earnings for the rest of their career.

The state could fund grants to private or nonprofit entities that are able to help long-term unemployed get back on their feet through career coaching, skill training where needed, and placement at a prospective employer at a subsidized initial rate with the employer paying back part of that subsidy upon hire. Such a program could be modeled after the successful Platform to Employment, which is limited to major cities, and has not yet come to Phoenix. But even if it did come to Phoenix, the needs of the long-term unemployed in Tucson, Flagstaff, Prescott and elsewhere would not be met—and the company likely doesn’t have the capacity to fully meet the needs in any city it works in.

Participating agencies would need to meet clear metrics and renewal of any grant would be contingent on placement, acceptable pay levels and employee and employer satisfaction,

Another promising project, the LA Fellows program, places skilled unemployed people as volunteers at nonprofit organizations—where they can build their skills and networks. Expanding this type of program might be more limited due to the challenges of dealing with a volunteer who also is actively looking for a job, but these volunteer possibilities would create opportunities for the unemployed to use and build their skill set in productive ways that could be beneficial to cash-strapped nonprofits as well as the volunteer.

In Boston, an experiment is underway to explore the effectiveness of career coaching, a service that can be bought on the private market, but again state grants could help provide the long-term unemployed the kind of one on one support, they need. If the search is successful, the now employed worker could help pay back part of the cost.

Another idea floated involves competitive grants aimed at boosting connections between training institutions such as community colleges and employers—something that already exists—which aim to develop partnerships and internships in which case part of the grant money could go to scholarships that would be partially paid back by the employer, if they hire the intern.

Arizona champions its entrepreneurial policy efforts, and here is where the state could become a national leader in helping the long-term unemployed reconnect with productive employment.

Dave Wells holds a doctorate in Political Economy and Public Policy and is the Research Director for the Grand Canyon Institute.

Reach the author at DWells@azgci.org or contact the Grand Canyon Institute at (602) 595-1025

The Grand Canyon Institute, a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, is a centrist think-thank led by a bipartisan group of former state lawmakers, economists, community leaders, and academicians. The Grand Canyon Institute serves as an independent voice reflecting a pragmatic approach to addressing economic, fiscal, budgetary and taxation issues confronting Arizona.

Grand Canyon Institute

P.O. Box 1008

Phoenix, AZ 85001-1008

GrandCanyonInstitute.org

Economic Impact Appendix

The Grand Canyon Institute forecasts that unemployment insurance recipients will fall 15 percent on a year to year basis during calendar year 2014, and that the long-term unemployed would have remained about 25 percent of all people receiving unemployment compensation. That leads to a projected monthly average of 11,100 people receiving extended unemployment benefits each week of $220. This yields $127 million in added income to households (11,100 recipients x $220/week x 52 weeks).

However, the counter situation is what would the households have done in the absence of the benefits? In most cases, they remain unemployed or would drop out of the labor force.

Farber and Valletta in an April 2013 San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank Working Paper estimate that extended unemployment benefits from 2009 to 2011 have increased unemployment duration by 7 percent. However, that duration increase only applies to those receiving benefits. In Arizona during the third quarter of 2013 about 25 percent of those unemployed were receiving state or federal unemployment benefits. This implies that of the state’s current 7.8 percent unemployment rate that without extended unemployment benefits, the rate would be 7.66 percent. For calendar year 2014, GCI presumes that Arizona’s average unemployment rate will be 7.5 percent and its labor force about 3 million.

Extended unemployment benefits using the Farber and Valletta estimate suggest that 3,900 more people are unemployed each month than would be without the benefits. However, there are two ways in which a person can be counted as not being employed. A person can find employment OR they can become discouraged and stop searching and drop out of the labor force. For the long-term unemployed the latter consequence is the more likely result. Farber and Valletta estimate that of those no longer being counted as unemployed if benefits are not extended, 25 percent find employment and 75 percent drop out of the labor force.

Thus, GCI removes 1,000 (approx. 25 percent of 3,900) long-term unemployed from the economic impact estimate, presuming that they would have found employment, resulting in 10,100 as the estimate of extended unemployment beneficiaries per month. This makes the direct impact $116 million (10,100 recipients x $220/week x 52 weeks).

The economic impact multiplier for unemployment benefits suggested by the Congressional Budget Office and Economic Policy Institute is 1.5. While that is a national multiplier—the national result is the sum of the state shares. While certainly there would be spending by extended unemployment insurance beneficiaries outside Arizona to other states, GCI expects that to be balanced by expenditures by households outside Arizona spending income that finds its way to Arizona. The national multiplier takes care of other leakages like expenditures on imported goods.

The result is a $174 million impact in Arizona (1.5 multiplier x 10,100 recipients x $220/week x 52 weeks).

A one percent increase in national GDP is expected to equate to a one percent growth in employment for 2014, as such, with national GDP approximately $17 trillion, the $174 million impact should increase employment growth in proportion to the growth in GDP at this stage of the economic recovery, meaning it would create 1,600 jobs in Arizona.

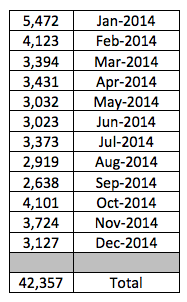

The 42,400 households expected to lose access to extended unemployment benefits comes from examining the initial payments of unemployment for Arizona for July through November 2013. Those receiving initial payments can expect they would terminate in six months. So a household receiving an initial payment in July 2013 would reach the six month threshold sometime in January 2014.

Based on evaluating trends in the percent of first payment recipients exhausting benefits in Arizona, a.k.a the exhaustion rate, GCI projects an exhaustion rate of 45 percent in 2014, somewhat less than in 2013.

The exhaustion rate is applied to initial payment amounts to project total exhaustions from January through May 2014. For projections for June through December 2014, GCI took 85 percent of the initial claims from 18 months earlier, so as also to capture expected seasonal variation. The 85 percent represents GCI’s estimate of a 15 percent year to year decline in people receiving unemployment benefits.

The results are below:

Number of Households Expected to Exhaust State Unemployment Benefits