Unemployment

Unemployment

Protecting Extended Unemployment Benefits in Arizona: Changing comparison to three years from two

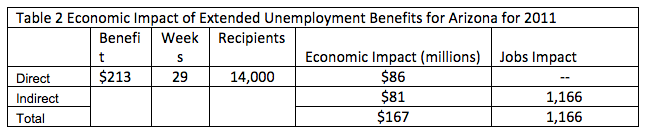

June 9, 2011Facing historically high rates of unemployment, not adjusting the comparison for the last 20 weeks of extended benefits from “two” to “three” years will unnecessarily harm thousands of Arizonans for something that’s beyond their control, the lack of sufficient jobs for those seeking them. In addition, the state will lose an infusion of $3.2 million in weekly benefits from the federal government that is expected to generate $167 million in economic returns and $6 million in new state and local tax revenue over the remainder of 2011.

Background Report

June 9, 2011

Protecting Extended Unemployment Benefits in Arizona: Changing comparison to three years from two

Facing historically high rates of unemployment, not adjusting the comparison for the last 20 weeks of extended benefits from “two” to “three” years will unnecessarily harm thousands of Arizonans for something that’s beyond their control, the lack of sufficient jobs for those seeking them. In addition, the state will lose an infusion of $3.2 million in weekly benefits from the federal government that is expected to generate $167 million in economic returns and $6 million in new state and local tax revenue over the remainder of 2011.

Introduction

During normal economic times, states provide up to 26 weeks of unemployment insurance to protect workers who have lost jobs through no fault of their own to support them financially during their job search process. Workers need a past work history to qualify, so new entrants to the labor market don’t qualify for benefits, nor do people who leave their jobs voluntarily. During the course of their unemployment, they need to document a continued active job search in order to retain benefits.

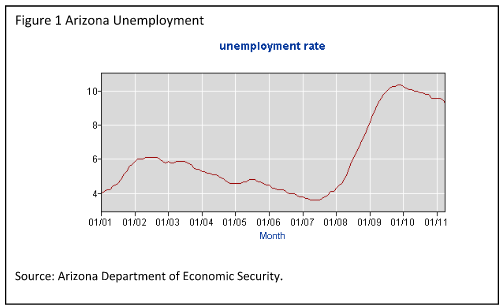

Unemployment is a lagging economic indicator, meaning that the economy slows before we see unemployment rates spike. When the economy slows down, businesses go through excess cash waiting to see whether the dip will continue and require layoffs, and in worse cases businesses close. Likewise, even though the recession has ended and we’ve moved into a recovery, unemployment rates lag, as businesses want to be certain growing demand will sustain itself before taking on the risk of hiring new employees. As a consequence, Arizona’s unemployment rate in April of 2011 was the same as it was in April of 2009, 9.3 percent. The earlier being in the midst of the recession, while the latter coming nearly two years into the recovery (the recession formally ended in June 2009—recessions start with two consecutive quarters of negative growth and end when growth becomes positive).

This recession has no parallel since the Great Depression, resulting from a real estate market bubble collapse and subsequent financial meltdown, which has hit Arizona especially hard due to Arizona’s historic reliance on construction as a key sector for economic growth.

Unemployment is composed of three conceptual pieces: frictional, structural and cyclical elements. Frictional unemployment is the normal amount of slack you have in any labor market where people occasionally move between jobs and businesses open and close.

Economist Joseph Schumpter aptly described capitalism as a process of “creative destruction,” and this process captures the second conceptual piece of unemployment, structural unemployment. During the late 1970’s the United States experienced a period of deindustrialization, as many manufacturing jobs began to move overseas, as a consequence a number of workers, such as autoworkers lost their jobs within industries that were shrinking, creating a mismatch between their well-developed skill set and available employment. This occurs continually in our economy and the result of these transitions is what we call structural unemployment. Most recently we’ve seen this phenomenon with how technological communications and computers have enabled outsourcing jobs in engineering and customer service, for instance.

The final type of unemployment is cyclical, referring to changes in macroeconomic business cycles. During boom times cyclical unemployment disappears and we have what is called “full employment” where unemployment rates equal frictional plus structural. These theoretical constructs are not always easily quantified in practice, so there’s some dispute about exactly when full-employment is achieved. However, when profits slip and the economy slows down, we quickly see evidence of cyclical unemployment, which has been responsible for the dramatic rise in unemployment that Arizona has experienced since 2008 (see Figure 1).

During times of cyclical unemployment, unemployment benefits are an automatic stabilizer helping smooth out consumption disruptions by aiding the unemployed during a time when there aren’t sufficient employment options due to cyclical conditions. When the economy experiences cyclical unemployment, the federal government frequently extends unemployment benefits beyond the initial 26 weeks. The current extensions began in 2008 under what is called Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) which has four tiers, enabling qualifying unemployed workers to receive up to 53 additional weeks of unemployment compensation.

- Tier 1 – Up to 20 weeks of EUC.

- Tier 2 – Up to an additional 14 weeks of EUC when Tier 1 benefits run out.

- Tier 3 – Effective 11/8/2009, up to an additional 13 weeks of EUC benefits are available when Tier 2 benefits run out.

- Tier 4 – Effective 11/8/2009, up to an additional 6 weeks of benefits are available when Tier 3 benefits run out.

If a worker remains unemployed after 79 weeks, they currently qualify for extended benefits for up to 20 weeks as unemployment rates exceed 6.5 percent, meaning workers can receive up to 99 weeks of unemployment compensation. This last 20 weeks is triggered by a state whose unemployment rate is at least 110 percent higher than it was two years previously. However, in December 2010, Congress authorized for the calendar year 2011 that states could extend the “look back” to three years. ”

In Arizona’s case statue sets it as two years. However, given economic circumstances, three years is a more appropriate period as Arizona’s unemployment rate was 4.9 percent in April of 2008, and first exceeded 6.5 percent when it hit 6.7 percent in September 2008. By sharp contrast in April 2009, unemployment stood at 9.3 percent. During the course of 2009, Arizona’s unemployment rate peaked at above 10 percent (see Figure 1). Hence, under a two-year “look back,” our current April 2011 unemployment rate of 9.3 percent fails to meet the criteria for these last 20 weeks of extended benefits.

Prolonged Cyclical Unemployment

Arizona’s most recent downturn as well as the country’s as a whole has been far deeper and prolonged than prior recessionary periods.

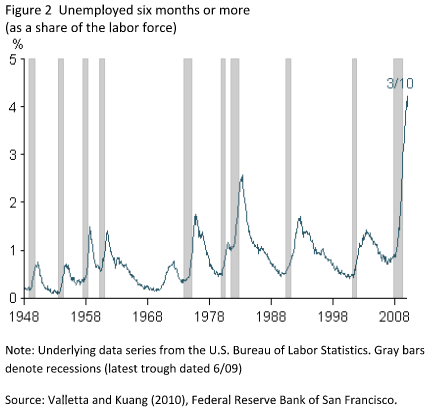

Even though the recession technically turned into recovery in July 2009, we see in Figures 1 and 2 that unemployment continued to rise and the share of workers experiencing six of more months of unemployment had not peaked.

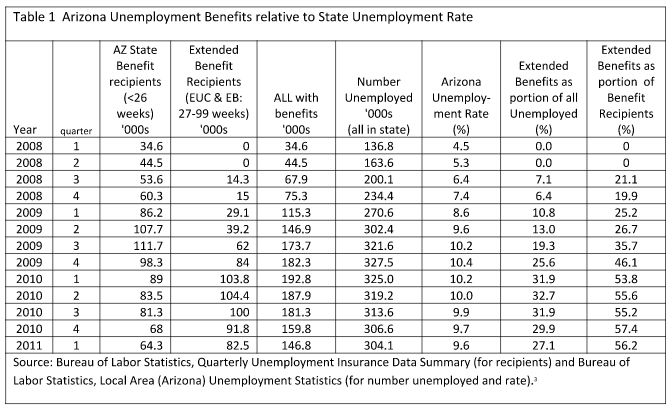

Looking at Arizona more carefully, we can see as the job market remained slack, the portion of Arizona workers moving to some kind of extended unemployment rose significantly from the last quarters of 2008 when the EUC programs began.

Even today, while in absolute terms, the number on extended benefits peaked a year after the recession ended, second quarter of 2010, the portion of benefit recipients relying on federal extended benefits continues to rise, suggesting that while fewer new people are becoming unemployed, those who have been unemployed for a longer period still struggle with finding work (see Table 1).

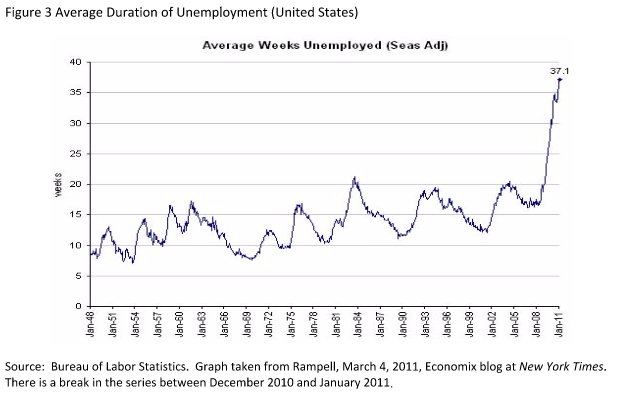

Another way to assess the impact of extended cyclical unemployment is to look at average unemployment durations. During this downturn, durations have become so extended that the Bureau of Labor Statistics has recently adjusted its cap to five years from two years. This data is captured in the monthly Current Population Survey, so includes workers receiving as well as those not receiving unemployment insurance benefits. In the past, a worker who reported being unemployed 30 months would be input as 24 months, whereas now it will be listed as 30. This methodological change began in January 2011 as the BLS found the number of unemployed workers actively seeking employment beyond two years reached 11 percent of those unemployed in the fourth quarter of 2010. The effect starting in January 2011 rises the duration by about 1.5 weeks from the prior system; as the economy recovers that will diminish. Figure 3 captures just how unprecedented the rise in unemployment duration is.

Duration of Unemployment

Studies generally find that unemployment benefits do have a positive impact on the duration of unemployment as they provide a safety net, insurance. However, many of these data sources come from times of lower unemployment. As a consequence one has to be cautious in extrapolating from studies based on workers unemployed less than 26 weeks during a comparatively more robust time.

We also have only weak support for unemployment insurance undermining the search effort. Karen Campbell and James Shirk of the Heritage Foundation in November 2008 suggest that unemployment insurance provides a strong disincentive to search for a job until the benefit is about to expire. However, once variables are properly controlled for the effect is cut in half as noted by Alan Krueger and Andreas Mueller, the research they cite.

Those eligible for UI search 13 minutes more on an average day than those who are not eligible. This difference, however, falls to 6 minutes when we control for observable characteristics such as age, education, sex, marital status, and a dummy for the presence of children. Those eligible for UI are generally older, more highly educated, and are more likely to be male as well as married (or cohabiting).

During the current economic downturn, we have unprecedented levels of unemployment, as unemployment insurance as a program was something that came out of the Great Depression, and statistical data collection has progressed a great deal since that time. Two studies that have looked at data from the current downturn from the San Francisco Federal Reserve and the Chicago Federal Reserve when applied to Arizona come to virtually identical conclusions, extended unemployment benefits have had a negligible impact on unemployment duration, about two weeks with 73 weeks of extended benefits available. The explanation is fairly simple. If there are insufficient jobs, the economy cannot absorb all those looking for work.

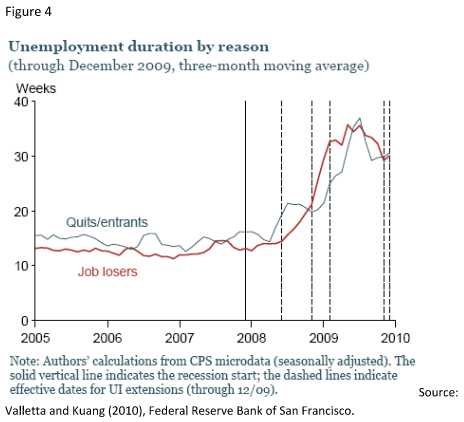

The San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank economists Rob Valletta and Katherine Kuang in April 2010 compared job leavers or entrants, who wouldn’t qualify for unemployment insurance, with job losers, who would qualify. Figure 4 illustrates their comparison graphically. Despite extended unemployment benefits that can now reach 99 weeks, a full 73 weeks beyond the half a year provided during better economic times, we see little deviation in the duration of unemployment.

Using the low unemployment period of 2006-2007 as the baseline, they project that the extended unemployment benefits have increased unemployment duration by 1.6 weeks. In other words every 6 weeks of eligibility for extended benefits only increased the duration of receiving benefits by one day.

Data sets rarely allow economists to look at just those receiving unemployment benefits, and not all those who qualify for unemployment benefits actually choose to take them. An underlying assumption of Valletta and Kuang is that those receiving unemployment benefits among job losers have similar durations to those who did not receive benefits.

Chicago Federal Reserve Bank economist Bhaskar Mazumder in April 2011 did a separate analysis. When one examine the assumptions and applies it to Arizona, we come to a similar conclusion as Valletta and Kuang. Mazumder considers the 5.1 percent that the nation had as its unemployment rate during the first six months of 2008 before extensions took effect as a “steady-state” rate. Applying findings from the economic research literature related to how unemployment duration is impacted by extended benefits. He finds that extended benefits have increased duration of unemployment by 2.8 weeks. However, one of his assumptions in generating that result is that 40 percent of unemployed workers receive benefits at the “steady-state.” While this is true nationwide, it is not true in Arizona. Arizona has consistently been among the lowest states in the country in the portion or unemployed workers receiving benefits. For instance, as seen in Table 1 for the first half of 2008 only 30.7 percent of unemployed workers picked up benefits. During times of lower unemployment in the state, the pick up rate has often been below 30 percent. The 2002 report Failing the Unemployed by the National Employment Law Project and The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, for the calendar year 2001 the United States averaged a 43.3 percent recipiency rate, while Arizona ranked near the bottom in the nation with 28.2 percent.

Assuming Arizona was three-fourths of the national average, then Mazumder’s estimate applied to Arizona is 2.1 weeks, just half a week longer than Valletta and Kuang. However, given that Arizona’s benefits replace a smaller portion of the average weekly wage than nearly every state in country, at 25.9 percent (ranking 50 out of 51), we should also suspect that the incentive to stay on unemployment benefits is lower in Arizona, an issue Mazumder doesn’t adjust for. Consequently, we should consider Mazumder’s estimate when applied to Arizona to be on the high side.

Economic Impact

Unemployment Insurance Benefits have a consumption smoothing impact for individual households, enabling them to handle better the crushing blow that a loss of income from employment can have. At the macro-level, unemployment benefits help the economy rebound from cyclical disruptions by enhancing overall consumer demand.

These effects are particularly prominent for the long-term unemployed. As economist Jonathan Gruber found in his research:

For longer spells, UI will provide the only source of consumption smoothing. Indeed, PSID data show while one-half of individuals who lose their jobs have savings before job loss, only 18.6 percent have saving of more than two months of income. Thus, spells that last more than a few months cannot be financed by own savings, inducing a larger consumption smoothing effect for UI.

To estimate the economic impact, we take the average monthly benefit for unemployment insurance recipients $213 and multiply it by the reported number of households currently eligible for the final 20 weeks of extended benefits, 15,000. This yields an infusion of $3.2 million into the state.

The three year look back expires at the end of 2011, which is 29 weeks after June 11. Although unemployment has lingered at historically high levels and unemployment rates, though falling in the state, will continue to require private sector growth to compensate for continued retention in public spending by the state of Arizona and localities. Analysis of Table 1 shows that long-term unemployed continue to be a high share of benefit recipients. Nonetheless, we assume the number of households in the 79-99 weeks of UI benefits will fall by year’s end to 13,000, so we assume the average weekly recipients being 14,000 for the remainder of the year. This gives us a direct effect of $86 million. However, we also have indirect effects.

IMPLAN is a modeling program based on the demographics of recipients of income and their spending patterns to determine within a geographically area the propensity for that infusion to be re-spent within given sectors of the economy generating direct (the infusion) and indirect (re-spending) impacts for an overall economic benefit and to estimate the number of jobs supported by it.

Table 2 shows the estimated economic impact based on the IMPLAN derived multiplier of 1.94 and the Jobs Multiplier of 14 (latter is jobs created/supported per $1 million in economic benefit). The total economic impact is $167 million. That $167 million will support 1,166 jobs.

We can also estimate the fiscal impact on the state. To do this, we look at the state’s annual revenue report and calculate sales taxes and income taxes as a percent of state gross product for 2010 and then extrapolate those percentages to the $167 million with some adjustments.

Sales Taxes: Sales taxes at all levels totaled $6 million in the 2010 fiscal year. However, voters passed Proposition 100 in May of 2010, raising the sales tax by 1 percent, assuming the typical rate was 8.3 percent before Prop. 100’s implementation, we get an adjusted sales tax receipts of $6.7 million which is 2.6 percent of GSP. The $167 million dollars can be expected to generate $4.4 million in new state and local sales taxes.

Income Taxes: We break income taxes into direct and indirect. For direct, we’re only considering the income taxes paid for by households receiving unemployment benefits. For indirect we’re considering income taxes (personal and corporate) for the state.

Direct: Unemployment Insurance benefits are taxable, and in some households a spouse may also be a source of income. So they do pay taxes. Individual income taxes measure 1.5 percent of GSP. However, they are disproportionately paid by wealthy households. So for our purposes we assume that the impacted households have an adjusted gross income of no more than $40,000. Department of Revenue Annual Reports for the most recent year available show that these households paid 9 percent of resident income taxes, yielding a modest $107,000 in state revenue.

Indirect: The re-spending should impact all income groups and corporations within the state. Personal and Corporate income taxes amount to 1.7 percent of GSP and this is multiplied by $81 million to yield a $1.4 million impact.

Collectively, we estimate a $5.9 million, or roughly $6 million improvement in state and local finances.

Conclusion

Economic analysis clearly demonstrates that the state and individual households will benefit significantly by making a “three” year look back instead of a “two” year look back. The state aims to reap $167 million in benefits, generating $6 million in added state and local tax revenue, while supporting 1,166 jobs.

Increased duration effects from these extended benefits are negligible as long as unemployment rates remain at high levels.

Compiled by Dave Wells, Ph.D.

Fellow, Grand Canyon Institute

with contributions from Jeff Chapman, Ph.D.

Fellow, Grand Canyon Institute