Water

Water

Groundwater: Getting to Safe Yield by 2025

February 23, 2015Groundwater: Getting to Safe Yield by 2025

Karen L. Smith, Ph.D.

Fellow, Grand Canyon Institute

Arizona has long depended on its groundwater resources, both to serve as a buffer from the effects of drought and as a sole water source to fuel its economy. As long as pumping groundwater is in balance with the amount of water recharged to the aquifer, safe yield is achieved. When more groundwater pumping occurs than is recharged, groundwater mining or overdraft occurs. The negative effects of groundwater mining are significant. As noted resource economist Henry Vaux writes, “Persistent overdraft is always self-terminating.” It leads to declining water tables, greater pumping depths that lead to increased costs, and can lead to land subsidence or earth fissures and poor water quality. The costs of subsidence are substantial: Luke Air Force Base and vicinity suffered about $3 million in damage(1992); at the Central Arizona Project (CAP) canal in Scottsdale costs of more than $1 million to repair subsidence impacts (1999 to present); at the McMicken Dam (2003-2006) costs of several million dollars to mitigate earth fissures undermining the structure; and in the Foothills development in the San Tan Mountains fissures opened dangerous holes in residential yards that crumbled driveways, exposed underground utilities and destabilized adjacent lands.[1] Arizona has attempted to manage its groundwater problem through the 1980 Groundwater Management Act (GMA). This seminal piece of legislation signaled a new era in water management for the state and toward a sustainable water management goal of safe yield by 2025 for the most populous areas of Arizona. Through a combination of vigorous regulation of groundwater pumping and a series of localized ten year management plans through the year 2025, the GMA would allow south- central Arizona to conserve precious groundwater resources for future use and stave off the negative effects of groundwater mining. Importantly, it established safe-yield as the benchmark for use of groundwater resources in Arizona’s critical groundwater areas that coincided with most of its population and economic activities. The GMA has been largely successful as the centerpiece of Arizona’s water management framework, but recent years have shown slippage in progress toward meeting the goal of safe yield. Some of these problems have existed since the GMA was passed, a result of negotiated concessions among the mines, farms and cities. Others are of our own making, in attempting to continue to do business in old ways the GMA meant to change. Safe yield of south-central Arizona’s aquifers remains a critical need for our water future. Achieving it will require both legislative and policy changes. This GCI report outlines what actions might be necessary in the short-term to reach safe yield by 2025 and what longer term work needs to occur to maintain it.

Policy Report

February 23, 2015

Groundwater: Getting to Safe Yield by 2025

Karen L. Smith, Ph.D.

Fellow, Grand Canyon Institute

Arizona has long depended on its groundwater resources, both to serve as a buffer from the effects of drought and as a sole water source to fuel its economy. As long as pumping groundwater is in balance with the amount of water recharged to the aquifer, safe yield is achieved. When more groundwater pumping occurs than is recharged, groundwater mining or overdraft occurs. The negative effects of groundwater mining are significant. As noted resource economist Henry Vaux writes, “Persistent overdraft is always self-terminating.” It leads to declining water tables, greater pumping depths that lead to increased costs, and can lead to land subsidence or earth fissures and poor water quality. The costs of subsidence are substantial: Luke Air Force Base and vicinity suffered about $3 million in damage(1992); at the Central Arizona Project (CAP) canal in Scottsdale costs of more than $1 million to repair subsidence impacts (1999 to present); at the McMicken Dam (2003-2006) costs of several million dollars to mitigate earth fissures undermining the structure; and in the Foothills development in the San Tan Mountains fissures opened dangerous holes in residential yards that crumbled driveways, exposed underground utilities and destabilized adjacent lands. Arizona has attempted to manage its groundwater problem through the 1980 Groundwater Management Act (GMA). This seminal piece of legislation signaled a new era in water management for the state and toward a sustainable water management goal of safe yield by 2025 for the most populous areas of Arizona. Through a combination of vigorous regulation of groundwater pumping and a series of localized ten year management plans through the year 2025, the GMA would allow south- central Arizona to conserve precious groundwater resources for future use and stave off the negative effects of groundwater mining. Importantly, it established safe-yield as the benchmark for use of groundwater resources in Arizona’s critical groundwater areas that coincided with most of its population and economic activities. The GMA has been largely successful as the centerpiece of Arizona’s water management framework, but recent years have shown slippage in progress toward meeting the goal of safe yield. Some of these problems have existed since the GMA was passed, a result of negotiated concessions among the mines, farms and cities. Others are of our own making, in attempting to continue to do business in old ways the GMA meant to change. Safe yield of south-central Arizona’s aquifers remains a critical need for our water future. Achieving it will require both legislative and policy changes. This GCI report outlines what actions might be necessary in the short-term to reach safe yield by 2025 and what longer term work needs to occur to maintain it.

The Groundwater Management Act of 1980

In 1980, Arizona used more than 5 million acre-feet of water each year, of which more than 60% was groundwater, to support the activities of about 2.7 million people. Pumping water out of an aquifer is similar to mining oil; once pumped, it’s gone forever. Groundwater mining or overdraft takes place when the amount of water pumped is greater than the amount replenished or recharged, which in 1980, exceeded recharge by 2.5 million acre-feet of water annually. Like people overdrawing their bank accounts and risking their futures, Arizonans in the central part of the state had been overdrafting their water accounts for decades. Multiple efforts had been made since the late 1930s trying to limit groundwater mining where it was the most serious, in Maricopa, Pinal and Pima counties, but despite the growing economic costs and physical reality of its negative effects, securing groundwater management legislation was not achieved until 1980. Even then, after nearly fifty years of studies and discussion of this problem, agreement came reluctantly. Bipartisan political leadership from Governor Bruce Babbitt (D) and Senate President Stan Turley (R) and House Majority Leader Burton Barr (R) was required to corral a skeptical and distrustful set of interest groups, including the mines, the cities and agriculture, and arrive at a fragile and grudging consensus that regulation of groundwater pumping in the state’s most populous areas could no longer be delayed; it required immediate action. They were “nudged” in great part by the federal government, which threatened to withhold funding for the Central Arizona Project (CAP) until the state did something about its groundwater mining problem. Finally, on June 11, 1980, the Arizona Legislature did something and passed the Groundwater Management Act (GMA) without amendment and with more than a two-thirds majority in each house. Governor Babbitt signed it into law the next day. This seminal piece of legislation signaled a new era in water management for the state toward a sustainable water management goal of balancing groundwater withdrawals with replenishment or “safe yield” by 2025 for the most populous areas of Arizona.

What did the legislature and those negotiating the groundwater code finally agree to do? Essentially, the GMA consisted of five key elements within critical management areas: all existing users of groundwater were to be grandfathered in and receive an allocation of groundwater pumping rights based on existing uses; new uses of groundwater would be substantially limited; since agricultural pumping comprised more than 80% of groundwater used, no new agriculture could occur outside existing agricultural lands; mandatory conservation would be required for most groundwater users; and an assured water supply program requiring a demonstration of a 100 year resource for new development. Municipal water providers were required to use renewable water supplies, such as those provided by the Central Arizona Project then under construction, to reduce pumping and provide for future growth. These actions were thought to be essential to halt the mining of groundwater.

How was this to be done? First, they defined and created critical groundwater management areas termed Active Management Areas (AMAs) within the south- central part of the state –in Phoenix, Pinal County, Prescott and Pima/Santa Cruz counties- where groundwater pumping would be controlled by a strong central state authority in the Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR), with a limited marketplace where groundwater rights could be acquired, chiefly from retiring agricultural lands and the purchase/lease of non-agricultural grandfathered rights. This would control the serious mining of groundwater and provide a means of allocating these groundwater resources to meet future changing needs. Groundwater would no longer be a private property right based on land ownership within these AMAs, but a public resource belonging to the people of the state where, through exercise of its police power, the legislature would prescribe “which uses of groundwater are most beneficial and economically effective.” Second, groundwater resources would be managed to achieve the AMA goals, which consist of three different yet complementary management schemes: the concept of safe yield, which achieves and maintains a long-term balance between the amount of groundwater withdrawn and the annual amount of natural and artificial recharge for the Tucson, Phoenix and Prescott AMAs; the concept of “optimal yield” in the Pinal AMA where agriculture is maintained as long as possible while recognizing the need to preserve groundwater for municipal uses; and for the Santa Cruz AMA, created in 1994 out of the Tucson AMA, a conjunctive management goal that requires safe yield for groundwater and protects the water tables of its surface waters. Those drafting the GMA thought the safe yield of the aquifers in Phoenix, Prescott and Tucson the best way to reduce the uncertainty associated with the unpredictable nature of water in a desert. As former ADWR director and water attorney Rita Pearson Maguire wrote:

They believed sustainable use could be achieved through the adoption of a series of water management programs that includes imposing progressively stringent conservation requirements on most groundwater users, replacing groundwater pumping with the delivery of surface water, encouraging the use of effluent and other reclaimed supplies, implementing artificial recharge programs, and the gradual retirement of agriculture through the urbanization of farmland and the purchase of irrigation rights. By achieving a balanced approach to pumping and recharging the aquifer, safe yield of the resource is assured.

Within these AMAs, since agricultural pumping was by far the largest user, agriculture groundwater use would be “frozen” at 1980 levels; there would be no new agriculture. The assumption was that urbanization and future growth would occur on farm lands so there would be a gradual diminishing of agricultural water use over time; many believed in 1980 that agriculture in south -central Arizona would go away by the time safe yield was required in 2025. There would be mandatory conservation for all users that would grow more stringent in each management plan as needed, with more restrictive gallons per capita per day allocations for water providers and higher efficiency rates for agriculture. There would be a limitation on what water could be transferred to a non-agricultural user. For mines, the GMA recognized that activity was tied to areas where mineral ore was located and that there wasn’t much flexibility in obtaining water; future uses would entail retiring farm land where possible to do so. Of all water users, mining was treated most preferentially as its permits for dewatering and mineral processing are for all intents and purposes an absolute right to pump water so they can mine the ore body. For cities and developers, the principle requirement, in addition to mandatory conservation and increasing use of renewable resources, was demonstration of an assured water supply for 100 years. For municipal water providers seeking a designation of assured water supply, the 100-year requirement is met through rolling 15 year plans that are reviewed by ADWR to ensure water supplies are met for the future no matter any changing conditions. For developments that secure their own assured water supply through a private water provider or through their own secured water supplies, the 100 year supply is evidenced by a one-time issuance of a certificate of assured supply.

The GMA, as negotiated and passed in 1980, included important principles for sustaining the economy, preserving groundwater for the future and reversing the longstanding practice of groundwater mining. As the principles became codified in law and policy, however, some of the assumptions upon which key provisions were made proved flawed and today, threaten the viability of achieving safe yield.

Groundwater Management at Work

Achieving consensus among the mines, cities and farms was difficult at best; it was perhaps the threat that the federal government would not fund construction of the CAP without effective groundwater management that was the ultimate spur to act. To get these disparate interests to agree, a number of concessions were required that have had an unintended negative effect on the GMA’s implementation. Key assumptions underlying the negotiations were that Colorado River renewable supplies through the CAP would replace most pumping; that urban development would occur on agricultural lands; that foreign competition in the copper mining business would gradually reduce the economic activity of mining in the state; and that city service areas under the assured water supply program would gradually subsume small water providers and those developments on their fringes. Because of what turned out to be an incorrect view of what the future would look like, the GMA does not correct all the “holes” in central Arizona’s proverbial groundwater bucket. Each sector of use –agriculture, industrial and municipal—received generous allocations of groundwater, but the municipal sector may be the only one the GMA thought would grow with reductions in groundwater in each succeeding management plan.

Agriculture

Farmers within the AMAs thought they had to give up more of their water future at passage of the GMA than other groups and uncertainty over the effect of limiting groundwater withdrawals on farm was very real. As a result, the initial allotments were based upon historic maximum use of water on a finite number of irrigable acres. These were termed Irrigation Grandfathered Rights or IGFRs. Annual water allotments for agricultural users under the GMA represented the amount of water a grower could use from wells, surface supplies (unless 100% surface water or CAP water was used) or both. Allotments were calculated for farms based on the highest number of acres irrigated during any one year from 1975-1979 as the benchmark to determine the water duty acres eligible to receive an allocation. Coincidentally, this period was the all-time peak of irrigated acreage in central Arizona and ADWR calculated therefore a very generous water duty for the first management plan based on average crop needs. To provide additional flexibility, the legislature created a flexibility account program (“flex credits”) where a farmer could “bank” water for future use. For example, if a farmer used less water in a given year than his allotment provided, he could bank the difference in a flex account; in a year he needed to use more water, he could use accumulated flex credits to pump more water. There are no limits on how many flex credits a farmer might accrue, no time period in which they must be used and any federally mandated acreage set-asides for program crops and other fallowed acreage also earn flex credits. Additionally, farmers can sell their credits to a grower within their irrigation district or sub-basin of their AMA. As of 2012, across all the AMAs, growers have accumulated nearly 5 million acre-feet of groundwater flex credits, or roughly double the total amount of groundwater pumped throughout the entire state in that year. The result is a situation where “most growers felt no constraint [from the GMA] on their irrigation use. . .tightened conservation provisions in the second and third management plans for the AMAs had no apparent effect on the quantity of water used by growers.” Many growers have adopted water conservation practices and technologies since the GMA was passed, but “factors other than AMA management plans have been largely responsible.”

Despite what now appear to be very generous initial allocations of water, growers contested ADWR’s application of the maximum feasible conservation efficiency language in the statutes, (especially the efficiency rate of 85% ADWR thought necessary for the Third Management Plan) and a water allotment based on historic rather than current crop choices. Farmers were successful in securing legislation in 2002 to eliminate the requirement to achieve maximum feasible conservation and instead, the legislature set the allotment on the basis of assigned irrigation efficiency of 80%. Additionally, the legislature authorized a Best Management Program (BMP) for agricultural water conservation for growers who choose to enter it that requires specific conservation practices; it also eliminates the quantitative limit (allocation) on groundwater use based on historic crops, although irrigation is still limited to historically irrigated acres. If a grower chooses to enter the BMP program, he can no longer participate in the flex credit program. Data collected to date on the effects of this program suggest there is a potential unintended consequence of growers using MORE groundwater than what would have been their groundwater allotment under the initial GMA agricultural conservation program. Further evaluation of this program is in order to ensure it is not actually doing harm to the goal of water management within the AMAs.

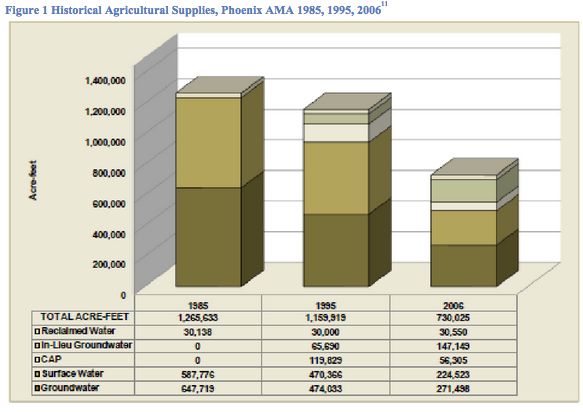

Agriculture plays a different role within each AMA, with Pinal continuing to show the largest agricultural water use at 92% of all water demand. Within the Phoenix AMA, agricultural water use has shrunk from nearly 60% of total water demand in 1985 to about 33% in 2006, but remains a substantial amount of water demand (about 730,000 acre-feet/year) of which more than half is groundwater or in-lieu groundwater. See Figure 1.

Although in-lieu groundwater is CAP water that is physically used in place of pumping groundwater, it counts as groundwater because the credits accrued will eventually be pumped. The reasons for the decline of agricultural water use are mostly related to urbanization of farmlands within the central part of the Salt River Valley, mainly the lands of the Salt River Project, leaving growers primarily farming in the western part of the AMA and in the southeastern part. A significant area within the western part of the Phoenix AMA, the Buckeye Waterlogged Area, is exempt from conservation requirements, allotments and payment of groundwater withdrawal fees. This area consists of lands served by the Arlington Canal Company, Buckeye Water Conservation and Drainage District and the St. John’s Irrigation District, as well as some private farmers. The exemption lasts until the end of the 4th Management period, December 31, 2019. In 2015, the ADWR must review the hydrologic conditions and submit a recommendation to the legislature and governor as to whether the exemption should continue.

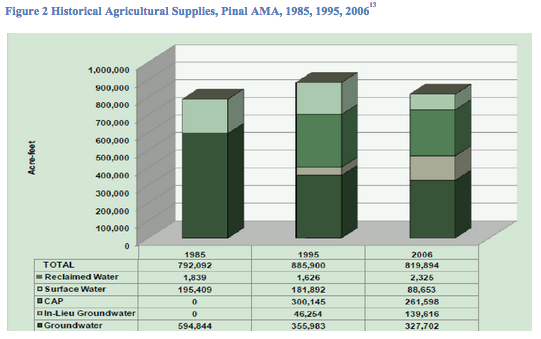

In the Pinal AMA, with its different management goal of “optimal yield”, which is a type of planned groundwater depletion, agricultural water use has actually grown since 1985 due to an increase in double cropping and is fairly constant at 820,000 acre-feet/year, of which more than half remains groundwater or in-lieu groundwater. See Figure 2 for Pinal AMA historic agricultural water.

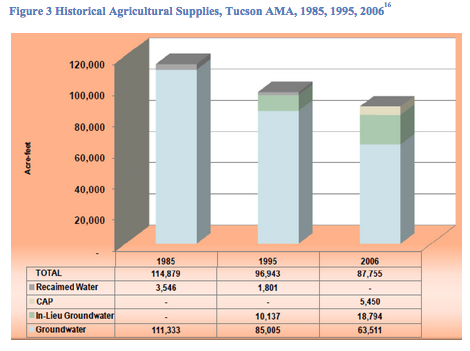

In the Tucson AMA, agriculture is a small demand sector at just under 88,000 acre-feet/year, illustrated by Figure 3, and is nearly all comprised of groundwater or in-lieu groundwater. Within the Prescott AMA, agriculture has become a very small part of the water demand, consisting of slightly less than 3,000 acre-feet in 2006, nearly all groundwater.

Agricultural irrigation does recharge the aquifer, however, and a significant amount of water that is not used consumptively by the crops or evaporated to the atmosphere returns as a “credit” to groundwater. ADWR estimates a lagged incidental recharge amount from agriculture based on irrigation that occurred 20 years prior; in other words, the agricultural incidental recharge factor of 193,285 acre-feet credited in 2006 is based on land irrigated in the 1980s. As time passes and fewer acres are irrigated, this incidental recharge factor will also decline.

Industrial

The industrial use category is defined in the GMA as a non-irrigation use of water not supplied by a city, town or private water company, including animal industry use and expanded animal industry use [dairies and feedlots]. It is a diverse group of water users, including turf-related facilities like golf courses, sand and gravel mining facilities, large-scale power plants, such as APS’ Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station and SRP’s San Tan Generating Station, dairy and cattle feedlot operations, and any large industrial user that withdraws groundwater directly and does not receive it from a municipal provider. Industrial use has been a small percent of AMA water use overall, although most of the water used is groundwater that is not replenished. This sector of water use was expected to grow along with the population, although the expectation was in the Phoenix AMA that most new non-residential uses would relate to golf courses and turf related facilities and occur within the service areas of cities where they would be served by municipal water providers; instead, power plants consume most industrial water. Within the Tucson AMA, the largest industrial use is metal mining and in the Pinal AMA, it is dairies. The Prescott AMA has a small amount of industrial use water that is used mostly on turf facilities, less than 1,500 acre-feet/year that is nearly all groundwater.

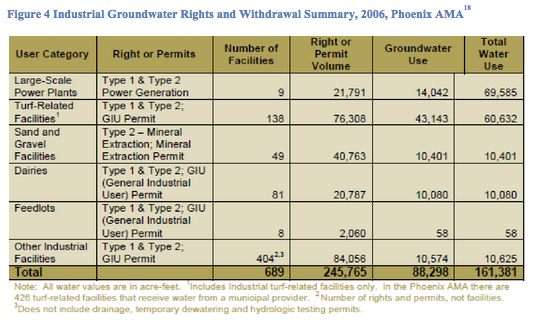

Industrial water use is associated with a variety of different groundwater rights and permits. Type 1 non-irrigation grandfathered rights are associated with land previously farmed and converted to a non-irrigation use; it may be sold or leased only with the land to which it was attached and the maximum amount of allowable pumping is 3 acre-feet/acre. Again, creation of these industrial rights was premised on the assumption that agriculture would gradually be eliminated as higher economic valued uses took over farmland. Type 2 non-irrigation grandfathered rights consist of a basic allocation of water for an historic industrial activity premised on the maximum amount pumped during any one year from 1975-1979. This allocation remains with the permit, whether fully used or not; water associated with a Type 2 non-irrigation right is not appurtenant to the land and can be leased, in whole or in part, or sold in whole. Examples of groundwater withdrawal permits for industrial use include General Industrial Use (GIU) and Mineral Extraction permits. There is no requirement to use renewable water supplies or to replenish the groundwater pumped. A large unused allotment balance associated with Type 2 rights has accrued within the AMAs as improvements in technology and efficiency have yielded less water used. Normally, that would be a positive for the AMA but for the ability of the user to sell or lease all of the water so “conserved” or not used to some other user. Figure 4 illustrates the amount of allowable groundwater for industrial use in the Phoenix AMA (nearly 246,000 acre-feet/year).

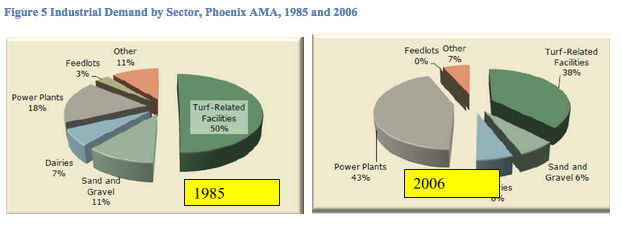

In 1985, the largest industrial user was turf –golf courses primarily. This has changed over time and now the largest direct user is power plants. However, the use of reclaimed water for industrial uses, such as at Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station and at turf-related facilities has increased substantially since 1980, now accounting for 38% of demand or nearly 63,000 acre-feet annually. Figure 5 illustrates the changing nature of the industrial water use sector within the Phoenix AMA.

Historically, sand and gravel facilities, dairies and feedlots have relied mostly on groundwater.

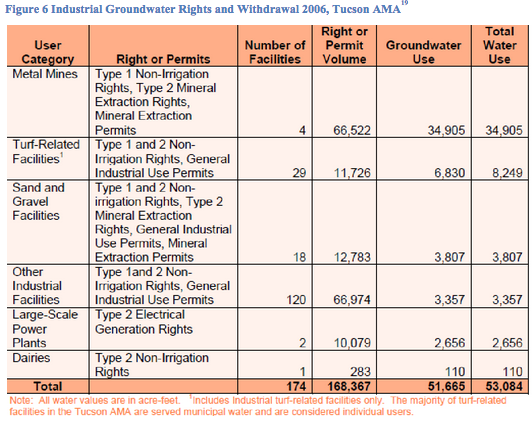

The Tucson AMA, the second most populated of the AMAs, has a relatively static industrial use sector, little changed between 1995 and 2006, with metal mining the main use and groundwater the primary source of supply. As of 2010, there were three active mines and one inactive mine in the AMA: ASARCO Mission and Silver Bell and Freeport-McMoRan Sierrita mines; Twin Buttes mine, adjacent to Sierrita, was inactive. As in the Phoenix AMA, about 30% of the industrial permitted volumes were used. See Figure 6 for the Tucson AMA permitted volumes by industrial sector.

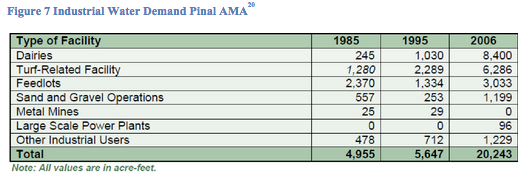

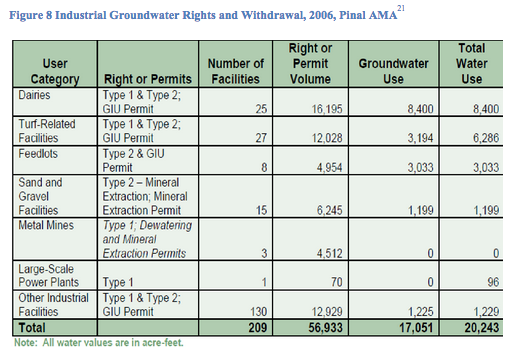

Within the Pinal AMA, industrial use has risen significantly since 1985 in nearly all categories. Rapid urbanization and high land prices provided incentive for dairies that had previously occupied lands in the Phoenix AMA to move south, quadrupling the amount of groundwater used. Turf related facilities and feedlots also grew. Of the more than 20,000 acre-feet of water used, more than 17,000 acre-feet/year consisted of groundwater. Figure 7 illustrates the types and amounts of industrial water used.

Like the other AMAs, much more water is associated with groundwater rights and permits in the Pinal AMA than has been used. See Figure 8 for Pinal AMA industrial groundwater rights and withdrawal.

While few facilities use a small volume of water for industrial purposes in the Prescott AMA compared to the other AMAs, the groundwater mining situation is made more difficult by the lack of renewable resources available to use. There is limited surface water within the AMA and available reclaimed water is used by the water providers that treat it. Therefore more than 90% of industrial use water is groundwater. As in the other AMAs, the allowable pumping exceeds the amount currently pumped. See Figure 9 for allowable pumping by type of use.

Figure 9 Industrial Groundwater Rights and Withdrawal, 2006, Prescott AMA

Conservation programs for the industrial use sector, combined with more efficient technologies and processes, has reduced industrial water use needs across the AMAs relative to allowable groundwater pumping.

Municipal

Perhaps the greatest success story of the GMA belongs to the cities and private water providers that make up the municipal water use sector. Across all the AMAs, the municipal water use sector has added substantial population and businesses while using less groundwater than in 1980. The GMA and the Assured Water Supply program provided municipal water providers a base allocation of groundwater that would decline over time. It required water providers to increasingly use greater volumes of renewable supplies, reducing their groundwater allocations in each management plan, and implement greater water conservation measures. Through the Assured Water Supply program, providers were encouraged to maximize use of reclaimed water, directly through turf and farm irrigation and power plant cooling, and indirectly through underground storage and recovery. The Assured Water Supply program spawned new water management programs that maximize the ability to use and store renewable water supplies underground. These have served providers especially well, such as the Underground Storage and Recovery program, Groundwater Savings Facilities “in-lieu storage”, and the Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment program. Other requirements that followed the GMA included state water conservation plumbing requirements and iterations of municipal water conservation programs, from the gallons per-capita per day (gpcd) to the modified non-capita water conservation program that allows each provider to identify the most appropriate conservation measures for their communities.

The municipal sector consists of four categories of water users: large providers (serving greater than 250 acre-feet /per year); small providers (serving less than 250 acre-feet/per year); domestic exempt well users; and individual users, such as schools, golf courses, lake facilities, cemeteries, homeowners’ associations and other general turf and landscaping that are served by a water provider. Several of the large and small water providers are private water companies, regulated by the Arizona Corporation Commission, which can affect the types of water available for use and the different conservation measures employed. Most of the people residing within the AMAs are served by a large water provider.

Within the Phoenix AMA, most large water providers have the benefit of a diverse supply of available renewable supplies available to them, including surface water from the Salt River Project, CAP water, and treated reclaimed water. The component of groundwater as part of the supply portfolio has been relatively small and has declined from 1985 to 2006. See Figure 10 for historic municipal water demand.

Figure 10 Municipal Water Demand, Phoenix AMA

Population growth is the single greatest factor affecting municipal water demand; about 3.6 million people lived within the Phoenix AMA in 2005. The location of where growth occurs affects the types of water supplies available. Generally, cities’ water services supply the central areas of the Phoenix AMA and private water companies supply development on the fringe. A significant portion of the demand from the municipalities’ service areas is met with renewable supplies, but demand for new subdivisions constructed within private water service areas is met largely from groundwater. Municipalities within the AMA also use a large portion of their reclaimed water. Figure 11 illustrates the growth and changing nature of the AMA municipal water supplies.

Figure 11 Historic Municipal Supplies, Phoenix AMA

Municipalities are also acting to increase their water supplies through aggressive underground storage and recovery programs; more than 410,000 acre-feet of excess CAP water and reclaimed water were stored underground in 2010. While trends for municipal use in the Phoenix AMA are positive, with less groundwater and more renewable supplies in use, there is a danger that can occur from more development occurring on the fringes, pumping groundwater and relying on the Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District, to provide its replacement.

Exempt wells are less a groundwater problem in the Phoenix AMA than in some of the others, although their number has increased due to dry lot subdivisions and lot splits occurring primarily on county-zoned land; groundwater use was estimated at about 5,400 acre-feet of water in 2006. ADWR has to estimate this use because it is not metered or reported in any way.

Within the Tucson AMA, there are fewer renewable water supplies available than in the Phoenix AMA and no large storage reservoir for CAP water. Although CAP water arrived in 1992, issues related to potable water distribution pipes in older homes have led Tucson Water, the largest provider in the AMA, to recharge most of its CAP water and recover it through pumping. Groundwater remains the dominant supply, providing more than 50% of all water used, although it has declined in amount even as population has increased. Tucson AMA has been aggressive in maximizing its use of reclaimed water and in cultivating a culture of conservation within the AMA. Figure 12 shows the growth and changing nature of the Tucson AMA’s municipal sector water supplies.

Figure 12 Historical Municipal Supplies, Tucson AMA

As in the Phoenix AMA, exempt wells have increased in number to more than 7,300 domestic wells, but estimated groundwater use is low at 721 acre-feet. Again, ADWR has to estimate this use because it is non-metered and not reported in any way.

Municipal water within the Pinal AMA is a very small sector of water use at about 3% of total water use, little changed since 1995. Most of the water used is groundwater. Since the Pinal AMA is not a safe-yield AMA, the amount of groundwater allocated to development is generous, without incentive to switch to renewable supplies. The building boom that occurred in the early 2000s is not yet reflected in municipal water demand. ADWR notes that between 2000-2006, overall municipal demand increased less than 10,000 acre-feet yet over 100,000 acre-feet per year of new subdivision build-out demand was issued a certificate of assured water supply and more than 90,000 acre-feet per year of additional demand was included in designations of assured water supply. Should these proposed developments ever be constructed, the change in the municipal sector in Pinal will be dramatic. Figure 13 illustrates historic water supplies in the AMA.

Figure 13 Historical Municipal Supplies, Pinal AMA

The Prescott AMA is the smallest of the AMAs under discussion here, but since it is almost entirely dependent on groundwater and reclaimed water for its supplies, it is in perhaps the most difficult situation trying to build a water resource management scheme premised on safe yield and renewable supplies. Moreover, the late declaration in 1999 that the Prescott AMA was no longer in safe yield, therefore triggering a number of GMA requirements, caused additional problems with a “rush to plat” that resulted in hundreds of subdivisions filing recorded plats in order to grandfather in pumping. This exacerbates a situation in the AMA where a generous groundwater allowance is already provided for those municipal providers who are designated due to the lack of supply alternatives and casts a shadow over water management planning. Added to this “unknown” is a dramatic increase in the number of exempt wells, from about 4,500 in 1985 to more than 11,000 in 2006, estimated to serve a population of about 20,000 people, and expected to grow. ADWR estimates the amount of groundwater pumped at more than 2,000 acre-feet/year, or about 11% of all water used in the municipal sector. Moreover this groundwater is not water that can be captured and treated for recharge to the aquifer as reclaimed water. It will be very difficult for the large water providers in this AMA to manage their water resources with the unknown volumes pumped by these exempt wells. See Figure 14 for the Prescott AMA historic municipal supplies.

Figure 14 Historic Municipal Supplies, Prescott AMA

Implementation of the GMA revealed the proverbial “holes in the groundwater bucket” that were the result of assumptions about the future that proved incorrect. The largest of these was the belief that urbanization would occur on agricultural lands, using less groundwater, and that direct industrial demand would grow primarily within city water service areas. The municipal water providers and others worked hard to augment their water supplies through recharging excess CAP water and reclaimed water. The storage volumes are impressive at more than 5 million acre-feet through 2006. Yet problems have arisen over the inability to manage storage and withdrawals within areas of hydrologic impact and to “protect” stored water from other users’ pumping. State law allows for recharge of renewable supplies anywhere within the AMA and recovery of those supplies also anywhere within the AMA. This has resulted in water providers from the southeast portion of the Phoenix AMA, as an example, recharging renewable supplies in the northwest portion of the AMA far away from the location of their eventual recovery. This doesn’t consider allowable pumping’s impact on water levels so that issues related to land subsidence and water quality remain. Other challenges have emerged as a result of continuing to allow real estate development on desert lands outside municipal service areas not on agricultural land, and the lack of any regulation concerning exempt domestic wells within AMAs. Real progress has been made toward reaching safe yield and accomplishments to date are impressive; yet it seems to be insufficient to help reach our goal. One lesson learned from implementing the GMA, however, is the need to analyze alternative futures in thinking about water management and safe yield. ADWR and water providers have built models examining different scenarios to estimate water demand, supplies and overdraft, based on whether population increases will be low or high, how agriculture will function and how the industrial sector will develop electric power. These scenarios, combined with equally arrayed water supply estimates, provide groundwater overdraft trends for each AMA and correspondingly, their ability to reach safe yield.

Groundwater Mining and the Outlook for 2025

While less groundwater is being used today with substantially more population and economic growth than in 1980, more water is pumped than is being recharged, both naturally and artificially. Our safe yield goal requires a long-term view; balancing withdrawals and recharge should not be done annually. There are years of drought that require more pumping than typical that needs to be recharged in years of abundant water. That’s why ADWR takes a 10 year approach of balancing groundwater withdrawals and recharge, with its management plans and assessments. The latest look shows how much more work is necessary to get to where we need to be. Just as groundwater has been used differently across the AMAs, each one has different challenges to overcome on the way to safe yield.

ADWR, working with local groundwater users, has developed future scenarios that estimate various levels of water demand and supplies, as well as the amount of allowable groundwater and overdraft. Their methodology is robust and considers not only increased population, but how water supplies might change over the next ten years as renewable supplies are maximized and groundwater pumping increases as a result. All three safe yield AMAs are projected to be in an overdraft state across the three varying growth scenarios. Within the Pinal AMA, as excess CAP supplies dwindle and become unavailable for in-lieu recharge, more groundwater pumping will ensue, with less incidental recharge, leaving fewer groundwater supplies for future growth.

Phoenix AMA

The most populated of the AMAs, projections for the Phoenix AMA assume an increase from about 3.1 million people in 2000 to about 6.1 million people in 2025. Figure 15 illustrates potential water demand across all water use sectors within the Phoenix AMA.

Figure 15 Historical and Projected 2025 Demand, Phoenix AMA

The primary sources of water supply in 2006 were surface water (38%), groundwater (31%) and CAP (18%). Surface water remains the primary supply in scenarios one and two, but in the high growth scenario three, groundwater becomes the dominant supply, adding to potential issues with overdraft. See Figure 16 for components of supply.

Figure 16 Historic and Projected Supplies, Phoenix AMA

Before looking at how much groundwater is contributing to overdraft, ADWR calculates estimated recharge volumes to the aquifer. These various types of recharge offset groundwater pumping so that in a state of safe-yield, withdrawals would nearly equal these recharge amounts. See Figure 17 for recharge projections.

Figure 17 Projected Recharge or Offsets to Overdraft, 2025, Phoenix AMA

Projected overdraft within the Phoenix AMA has an estimated range of 154,000 acre-feet/year to nearly 500,000 acre-feet/year without the groundwater allowance for the municipal sector included. These overdraft estimates do not account for the use of any agricultural flex credits that would certainly move the estimate of overdraft higher. See Figure 18 for the projected overdraft for the Phoenix AMA in 2025.

Figure 18 Projected Overdraft, 2025, Phoenix AMA

The groundwater overdraft includes allowable pumping such as the amount of groundwater withdrawn where no replenishment is required, such as agricultural irrigation allotments (IGFRs), Type 1 and Type 2 rights, groundwater withdrawal permits like GIUs, exempt wells, and service area rights operated by undesignated municipal providers serving customers not covered by a certificate of assured water supply, in addition to the municipal sector allowance shown above.

There is no scenario analyzed that has the Phoenix AMA reaching safe yield by 2025. Despite the very good

efforts undertaken to date to move to renewable supplies and increase conservation, more allowable pumping than recharge in the Phoenix AMA is occurring and will occur over the next ten years.

Tucson AMA

The Tucson AMA differs significantly from the Phoenix AMA in the composition of its water supplies and water use demands. Water supplies for this AMA are chiefly groundwater, with CAP water used both directly and indirectly, and increased use of reclaimed water. Population for this AMA in 2000 was about 836,000; projections through 2025 are 1.4 million. Water demand changes slightly, although the projected groundwater use under the three scenarios could be substantial. More significant demand fluctuations occur in estimating water use for the metal mining sector, as foreign competition, operational conditions and potential for a new mine could change groundwater use within the AMA. Figure 19 illustrates projected water demands by sector for the Tucson AMA.

Figure 19 Historic and Projected Demand, 2025, Tucson AMA

Even with increased use of CAP water and reclaimed water, the use of groundwater is expected to increase across all growth scenarios. Where growth occurs will matter – if it continues north along the Marana corridor on previously agricultural lands, the transition of supplies and increased reclaimed water will limit mined groundwater. See Figure 20 for projected water supplies.

Figure20 Projected Supplies, 2025, Tucson AMA

In order to estimate potential groundwater overdraft for this AMA, offsets to withdrawals were calculated. For Tucson AMA, the range is between 135,000 acre-feet/year and 146,000 acre-feet/year. See Figure 21 for recharge to aquifer or offsets to pumping.

Figure 21 Projected Offsets to Overdraft, 2025, Tucson AMA

Considering that groundwater is the main source of supply in this AMA, it’s perhaps not surprising that the Tucson AMA fails to achieve safe-yield under any of the estimated scenarios; the projected overdraft ranges from about 30,000 acre-feet in the lower growth scenario to about 139,000 acre-feet under the high growth scenario. Yet the overdraft amounts are not overwhelming and can be managed if all water use sectors contribute to reducing groundwater use. This projected overdraft includes allowable groundwater withdrawals from IGFRs, Type 1 and Type 2 rights, groundwater withdrawal permits, exempt well, and non-designated service area rights. See Figure 23 for projected overdraft with allowable municipal groundwater pumping and without it.

Figure 22 Projected Overdraft, 2025, Tucson AMA

As in the Phoenix AMA, the municipal use sector has done an excellent job of reducing groundwater consumption through use of renewable supplies and enhanced conservation; other sectors within the AMA continue to face challenges in reducing their groundwater use. Limited CAP/reclaimed water delivery infrastructure and availability of renewable supplies makes it difficult for agricultural and industrial users to contribute to achieving safe-yield.

Prescott AMA

Although the smallest and least populated of the safe-yield AMAs, Prescott’s challenges might be some of the most daunting. In 2000, the Prescott AMA population was about 90,000; in 2025 it is estimated at about 200,000. With very little available surface water and no access to CAP water, the AMA’s only significant renewable supplies are reclaimed water. Its large water providers in the municipal use sector have greater allowances of groundwater as a result. The more groundwater pumped, the more difficult it will be to reach the goal of safe-yield. New subdivision development will be affected by the lack of renewable supplies, as consistency with the water management goal requires full use of renewable water after 2025; water providers will need to do more to enhance their recharge and direct use of reclaimed water. Since the agricultural and industrial use sector are small within this AMA, key indicators for safe yield lie within the municipal sector, including the exempt domestic well water use. See Figure 23 for projected supplies and Figure 24 for projected demand.

Figure 23 Projected Water Supplies, Prescott AMA

Figure 24 Projected Water Demand, Prescott AMA

Since the municipal water use sector is by far the largest within this AMA and the one expected to grow the most, it is important to see where the demand is projected to occur. See Figure 25 for the amounts of use estimated to occur among the large providers (City of Prescott and Town of Prescott Valley), small providers and exempt domestic well uses.

Figure 25 Projected Municipal Demand, 2025, Prescott AMA

Offsets to pumping or recharge to groundwater are not as robust within this AMA as limited agriculture and other irrigation activities do not provide the kinds of incidental recharge seen within the other AMAs. Moreover, the nature of the hydrogeology of this AMA allows for a substantial amount of outflow of groundwater from the basin. See Figure 26 for offsets to pumping.

Figure 26 Offsets to Pumping, Prescott AMA

Overdraft will occur over all three growth scenarios, although the difference among the three is not substantial, from a low growth scenario overdraft of about 20,000 acre-feet and a high growth scenario of about 24,000 acre-feet. See Figure 27 for projected overdraft within the Prescott AMA.

Figure 27 Projected Overdraft, 2025, Prescott AMA

Unlike the other AMAs, the municipal water use sector is the only one that can work to achieve safe yield and it can do so only by reducing its groundwater pumping, maximizing its use of reclaimed water and augmenting its water supplies, in this case, through imported groundwater from the Big Chino Sub-basin of the Verde River Groundwater Basin that lies to the north of the AMA.

Pinal AMA

The water management goal for the Pinal AMA is currently different from the safe-yield AMAs in that it anticipates groundwater depletion from agricultural pumping, while also expecting that sufficient supplies will be available for any municipal growth. This sets an obvious conflict within the AMA that water users are just beginning to consider. The population of the AMA in 2000 was about 100,000 and is estimated to grow dramatically to about 600,000 in 2025. Some of this growth may not occur, as the housing boom that drove it in the early 2000s has clearly cooled substantially. Yet there remain, as indicated earlier, a significant number of platted subdivisions with issued certificates of assured water supply waiting to be built. Projected water demand for the Pinal AMA is illustrated in Figure 28.

Figure 28 Projected Water Demand, 2025, Pinal AMA

Projected water supplies within the AMA show continued use of CAP water, nearly one-third from increases in Indian agriculture, but substantially increased use of groundwater to meet demand across all water use sectors.

Large recharge volumes will offset groundwater pumping under lower growth scenario one, but significant groundwater overdraft is projected under scenarios two and three.

Figure 29 Projected Water Supplies, 2025, Pinal AMA

Continued irrigated agriculture throughout the AMA will contribute to recharge over time, but the large amounts expected in the way of incidental recharge by 2025 results from irrigation conducted in the year 2005. See Figure 30 for projected offsets to groundwater pumping.

Figure 30 Projected Offsets to Pumping, 2025, Pinal AMA

Figure 31 shows the range of potential overdraft/surplus within the Pinal AMA, with and without the allowance for the municipal use sector. Again, a substantial amount of groundwater pumping is allowable pumping, including IGFRs, Type 1 and Type 2 rights, groundwater withdrawal permits, exempt well and non-designated service area rights.

Figure 31 Projected Overdraft/Surplus, 2025, Pinal AMA

As long as irrigated agriculture remains the dominant water use within the AMA, it will contribute significantly to incidental recharge that offsets pumping. Still, if growth in the municipal use sector accelerates as predicted, overdraft will be substantial at more than 400,000 acre-feet/year. Water users within this AMA will need to discuss whether the planned depletion water management goal still suits the future of this AMA.

All four AMAs under discussion here illustrate the differences of water demand and supplies across south central Arizona, and the local conditions under which groundwater pumping occurs. The Arizona model of a strong central authority in ADWR that establishes regulatory conditions for pumping, and “which uses of groundwater are most beneficial and economically effective,” combined with local groundwater users convening to determine how it should occur, is the right formula for success in achieving the Legislature’s goals to conserve, protect and allocate the use of groundwater resources of the state and to provide a framework for the comprehensive management and regulation of the withdrawal, transportation, use, conservation and conveyance of rights to use the groundwater in this state. It is a commitment to safe-yield that must be pursued with vigor and purpose for the economic and general well-being of this state. As discussed throughout this report, while significant progress has been made in all three safe-yield AMAs, none will reach safe-yield by 2025 without added steps. See Figure 32 for the estimated overdraft in each AMA under all three demand scenarios. The following recommendations, if implemented within the next year or two, will move each AMA near the goal of safe-yield.

Committing to Reach Safe-Yield by 2025.

More than a decade ago, the major water use sectors met for two years within the framework of Governor Jane Dee Hull’s Water Management Commission to evaluate what needed to be done to reach safe yield by 2025. The conclusions reached then about required actions are as true today as then, yet remain elusive. Arizona’s need for effective groundwater management is critical, in the face of decades-long drought, a growing population and effects of a changing climate. The “holes in the bucket” are well-known as are possible solutions.

First, industrial users of groundwater not served by a municipal provider need to shift their water use to renewable supplies if possible and replenish any remaining mined groundwater. Renewable water use and groundwater replenishment can no longer be a requirement born only by the municipal use sector. This can be phased-in over a period of time like 5 years, but we will not reach safe yield when a growing use sector is not contributing to the goal. Adding replenishment requirements to CAGRD further complicates its current obligations so thought must be given to focusing CAGRD’s responsibilities to replenish on existing users of groundwater, municipal and industrial, instead of adding new uses to its replenishment portfolio. In this way we can start patching the holes in the bucket instead of adding to them. We may also want to re-think the viability of a flat industrial allotment of groundwater associated in a highly transferrable Type 2 right that never diminishes in size despite greater efficiencies in industrial processes and technologies, essentially negating all that is gained through conservation. Perhaps this groundwater right is one that should diminish over time as does the municipal provider allocation so that by 2025, only renewable supplies and a small groundwater allowance might be used. Unlike the use of renewable supplies and replenishment for industrial users, this concept has not been the subject of discussion among water users within AMAs and so needs to be considered as part of the continuing conversations on what will be required to reach and maintain safe yield. The requirement for industrial users to use renewable supplies and replenish mined groundwater, however, has been discussed since the Hull Water Management Commission. Legislation is needed to require industrial users to contribute to reaching safe yield and after twelve years, must be obtained.

Figure 32 Projected Overdraft All AMAs 2025

Second, development must be steered toward lands with existing rights, such as agricultural lands, and not on the fringes of raw desert that access solely groundwater. The framers of the GMA thought this is where development would occur and as a result, agriculture was provided a generous allocation of groundwater with the thought that cities and towns would expand across these lands. While this has occurred to a great extent on the lands of SRP, it is not happening in other parts of AMAs. Creation of the CAGRD, a water management innovation with good intent, has grown too big, with replenishment obligations larger than might reasonably be met, and with municipal water providers competing with CAGRD for finite renewable supplies. This problem with allowing development to mine groundwater in exchange for CAGRD replenishing it anywhere within the AMA encourages development on cheap desert land, away from where the water is, thereby contributing to negative effects of declining water levels through pumping far away from the site of recharge, and exacerbating the difficulty in reaching safe yield. This is a wicked problem for a regional economy still dependent on growth to fuel it. As a first step, CAGRD must be allowed the ability to “pause,” to place a moratorium on adding new lands and service areas to its replenishment obligation until it has been able to secure sufficient renewable supplies for its existing obligations, including any proposed replenishment for existing industrial users. Secondly, municipal and county planning officials need to consider whether any additional incentives are required to induce developers to build on agricultural lands or whether ordinances that provide for it need strengthening. As well, the Arizona Corporation Commission should rethink granting certificates of convenience and necessity to water providers sprouting to pump groundwater to new development without considering the real effects on an AMA’s water management goal. Third, and this is something ADWR is currently pursuing with all groundwater users, change to the statute that allows groundwater replenishment anywhere within an AMA must occur. We know now that recharge in northwest Phoenix AMA does nothing to help the southeast Phoenix AMA with water management if groundwater levels continue to drop, even if the pumping is allowed and is counted as “renewable” water. The discussions concerning enhanced aquifer management should conclude soon with proposed legislation to address this problem.

Finally, it is time to address the “third rail” of AMA water management: exempt wells that have no obligation to contribute to safe yield. This is a more significant issue in the Prescott AMA than in some of the others, but at a minimum, the Legislature should revisit the recommendation from the Hull Water Management Commission to reduce the amount of groundwater pumped to 20 gallons per minute (gpm) from the current limit of 35 gpm. As well, it is time to begin to collect data on exempt wells – how many there are, how many people are served and actual volumes pumped. Limited efforts to begin voluntary data collection have met with few takers. If you have the ability to drill a well, you should have the responsibility to measure what you pump. It’s as simple as that. This can be accomplished in concert with university researchers if the idea of AMA data collection is unpalatable. But no matter how it is done, it must begin.

There are other issues that must be addressed longer term. We need to understand better the effects of the agricultural best management practices program on agricultural water use. As early as 2002, some water leaders expressed concern over the ability of growers to actually use more water than under the base allocation program. It appears this might be the case, but we need to collect more data and analyze the results before reaching the conclusion that this is counter-productive. This should be a priority for ADWR over the next few years. We need to explore more opportunities to match various qualities of water with different uses, so that poorer quality water might find an appropriate use instead of potable water or mined groundwater. This was a recommendation of Governor Brewer’s Blue Ribbon Commission on Sustainable Water Use but like other recommendations, has languished due to lack of resources. These should be revisited again for implementation. Additionally, municipalities and counties need to explore opportunities to reduce the impact to groundwater from undesignated, certificated and pre-designation platted subdivisions. Finally, we must begin to fund our water infrastructure needs through a revenue stream secure from legislative sweeps. We know that in some AMAs the use of renewable water supplies is constrained by the lack of a pipeline to bring reclaimed water or CAP water to all water users. The Legislature created the Water Supply Development Fund within the Water Infrastructure Finance Authority as a means to provide low-interest loans for water infrastructure. It remains to be funded. We need to find a way to finance our existing and necessary water needs or there is no way we will be able to meet our future needs. Many discussions have already occurred on how this might be done, but resistance has been high. The Legislature should consider sponsoring a commission to debate the best ways to fund water infrastructure for Arizona and like the GMA, support the recommendations in a bipartisan manner.

We have achieved much in our efforts to use water sustainably and reduce our mining of groundwater. As we consider a future where recurring drought and diminished surface water supplies make this more difficult, and the temptation to scurry for new water supplies commands all our attention, we must first remember our commitment to safe yield. This is a large part of what makes Arizona “water smart.” The costs of persistent overdraft are indeed “self-terminating,” and the millions already spent to remedy effects of earth fissures and subsidence and the untold costs of deepening wells and poorer water quality are stark reminders of what failure to achieve safe yield may mean. First things first: continue to reduce groundwater mining and expand our conservation efforts. To move forward, the Legislature should consider legislation in 2015 to implement some of the ideas we know were needed in 2002:

- Industrial users of groundwater not served by a municipal provider need to use renewable supplies and replenish their mined groundwater. This can no longer be a requirement born only by the municipal use sector. This can be phased-in over a period of time like 5 years, but we will not reach safe yield when a growing use sector is not contributing to the goal.

- CAGRD must be allowed the ability to “pause,” to place a moratorium on adding new lands and service areas to its replenishment obligation until it has been able to secure sufficient renewable supplies for its existing obligations, including new authority to serve existing industrial use.

- Reduce the amount of groundwater pumped from exempt wells to 20 gallons per minute (gpm) from the current limit of 35 gpm. Explore data collection mechanisms for exempt well pumping volumes.

We have ten years left to reach safe yield. We can do this, with a commitment to succeed and a shared responsibility and commitment by all water users.

Karen L. Smith, Ph.D. is a fellow of the Grand Canyon Institute and an adjunct professor at Arizona State University. Previously, Dr. Smith served as Water Quality Director at the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality and Deputy Director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources.

Reach the author at KSmith@azgci.org or contact the Grand Canyon Institute at (602) 595-1025.

Additional reports on water issues by the Grand Canyon Institute include Arizona at the Crossroads: Water Scarcity or Water Sustainability (2011) and The Third Way: Accommodating Agricultural and Urban Growth (2012). Both reports are available online at www.GrandCanyonInstitute.org

The Grand Canyon Institute, a 501(c) 3 nonprofit organization, is a centrist think tank led by a bipartisan group of former state lawmakers, economists, community leaders and academicians. The Grand Canyon Institute serves as an independent voice reflecting a pragmatic approach to addressing economic, fiscal, budgetary and taxation issues confronting Arizona.

Grand Canyon Institute

P.O. Box 1008

Phoenix, Arizona 85001-1008