Policy Brief

December 9, 2019

Arizona Needs to Address Unemployment Compensation

to Ensure Families are Protected Before the Next Recession

Dave Wells, Ph.D., Research Director

Key Findings

- Arizona is the only state where a person working 25 hours per week earning $12 per hour who loses her job through no fault of her own does not qualify for unemployment insurance benefits.

- Arizona’s unemployment benefit cap is one of the lowest in the United States on par with Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi, having remained unchanged since 2004.

- Arizona’s unemployment insurance program is woefully unprepared for the next recession, putting individuals and families with children at risk of housing and food insecurity and marital breakdown.

Summary

Arizona combines the hardest to access unemployment benefits in the country with a very low cap on benefits leaving Arizona families insufficiently protected from the next recession. This contributes to housing and food insecurity, undermines marriages, and places children at risk, which can become catastrophic in an economic downturn. Households most likely to experience unemployment are below the 40th percentile in income and have insufficient savings to survive a significant loss of income without substantial risk to children.

Benefits are harder to access in Arizona than any other state. Arizona is the only state in the country where a worker who loses a 25-hour per week $12 an hour job does not qualify for unemployment benefits. Weekly benefits are capped at $240 for those that qualify for support. So a worker who loses a job that paid the average weekly wage of $980 receives only one-quarter of her former wages in weekly unemployment benefits. In comparison, other Southwestern states, including Texas, pay half of lost wages. Arizona should amend its program to match the other Southwestern states.

Recommendations

Benefits — Arizona should increase the cap on unemployment benefits to $490 per week, one half of the average weekly wage of the prior calendar year, and adjust this amount annually. Arizona should introduce a dependent allowance of $25 per week per dependent with a cap of $50 per week.

Accessibility — Arizona should change the minimum earnings required to qualify for benefits from earning in a calendar quarter 390 hours times minimum wage (the highest amount in the country) to 260 hours times minimum wage ($3,120 next year) OR alternatively $7,000 over the statutory four-quarter base period (as a minimum annual amount).

Remove job acceptance requirement —Arizona’s legislature should follow the recommendation of the federal government and remove the potentially unlawful portion of Chapter 340 (SB1398), of the 53rd Legislative Session (2018), so that those collecting unemployment benefits are no longer required to take jobs that pose significant challenges in terms of travel, hours, or pay level, in order to preserve their rights to unemployment insurance benefits.

Introduction

The U.S. Department of Labor’s November 2019 jobs report showed robust growth with 266,000 jobs created with a national unemployment rate at a 50-year low. It marked the 110th consecutive month nationally of employment growth. Arizona’s economy remains strong, though the state’s unemployment rate remains about one percent higher than the national rate and higher than the unemployment rate in 2007. The state gained 72,000 jobs from October 2018 to October 2019, which represents a pace of job growth faster than the national rate.

So, with these kinds of numbers, why focus on Arizona’s unemployment system?

Because Arizona’s unemployment system is woefully underprepared for the next recession.

Last legislative session, Governor Ducey successfully urged lawmakers to increase the budget stabilization (rainy day) fund, to $1 billion. The Legislature and the Governor worked together to ensure that the state was financially prepared for the next economic downturn.

By contrast, In Arizona, a worker earning the average weekly wage of $980 a week, who loses her job through no fault of her own, receives only one-fourth of her employment earnings with Arizona’s unemployment compensation system. A worker earning minimum wage for 25 hours weekly, would discover that she does not even qualify for unemployment benefits. Very few households can afford that loss of income without significant repercussions. Under the current formula for calculating unemployment benefits, Arizona workers would experience some of the harshest consequences of unemployment in the nation.

Arizona has not adjusted its maximum unemployment compensation in 15 years. As a result, the weekly $240 cap in paid unemployment insurance benefits, which was last raised in 2004, is only worth about $175 in 2004 dollars. When the cap was adjusted in 2004, it was still third lowest in the country.

The median American household has about $12,000 in savings, but that amount drops dramatically when looking at household savings below that amount. Among households between the 20th and 40th percentile in income, median savings is less than $1,000—not enough to survive a significant loss of income without substantial risk to children. The median household in the bottom 20th percentile of income has no savings at all—living paycheck to paycheck. The households that have the least savings are ones that are also most likely to have young children, so inadequate unemployment compensation places these children and their families at risk for divorce or other family disruptions as well as greater mental and physical health issues.

Recommendations:

- Change the minimum income to qualify for unemployment benefits in a calendar year quarter from 390 x minimum wage (30 weekly hours if at minimum wage) to 260 x minimum wage (20 weekly hours if at minimum wage) OR alternatively $7,000 for the base period (four quarters).

- Replace the $240 cap on weekly benefits with a cap of 50 percent of the average weekly wage of covered workers from the prior calendar year. In 2018, Arizona’s average weekly wage was $980, so this would make the cap $490 in line with all other Southwestern states

- Following New Mexico, allow a dependent allowance of $25 per dependent, per week, up to a maximum of $50 per week, not to exceed half of the weekly benefit without the dependent allowance. Given the impact of unemployment benefits for households with children and disabled adults, this formula will help reduce the impact of unemployment on some of the most vulnerable populations within the state.

- Rescind the portion of Chapter 340 (SB1398), of the 53rd Legislative Session (2018), that forces unemployment recipients to accept any job that is offered them or lose benefits if they have been on unemployment for at least four weeks. The federal government has already alerted the state that the law is in violation of federal requirements.

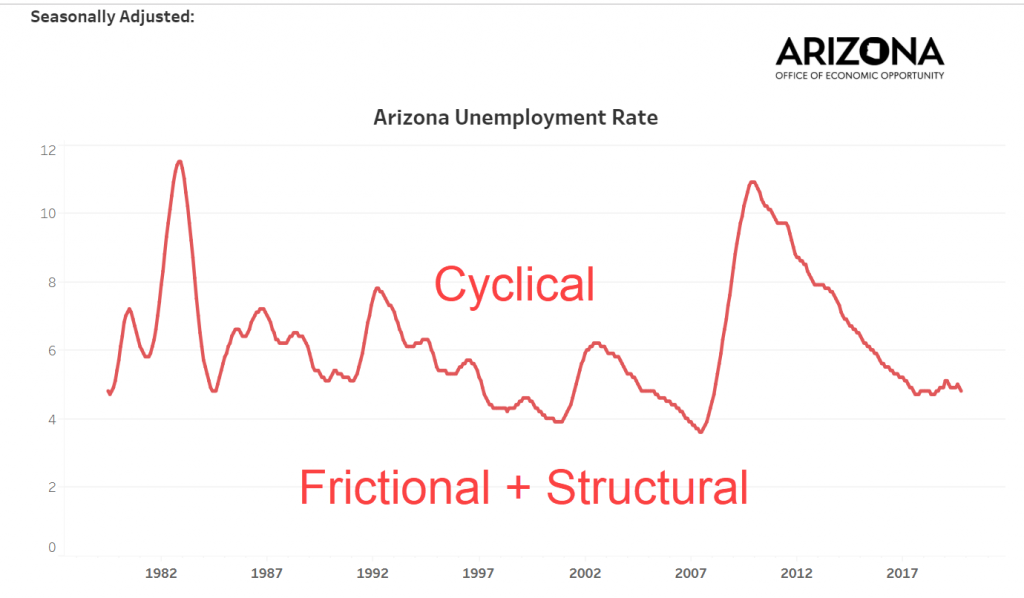

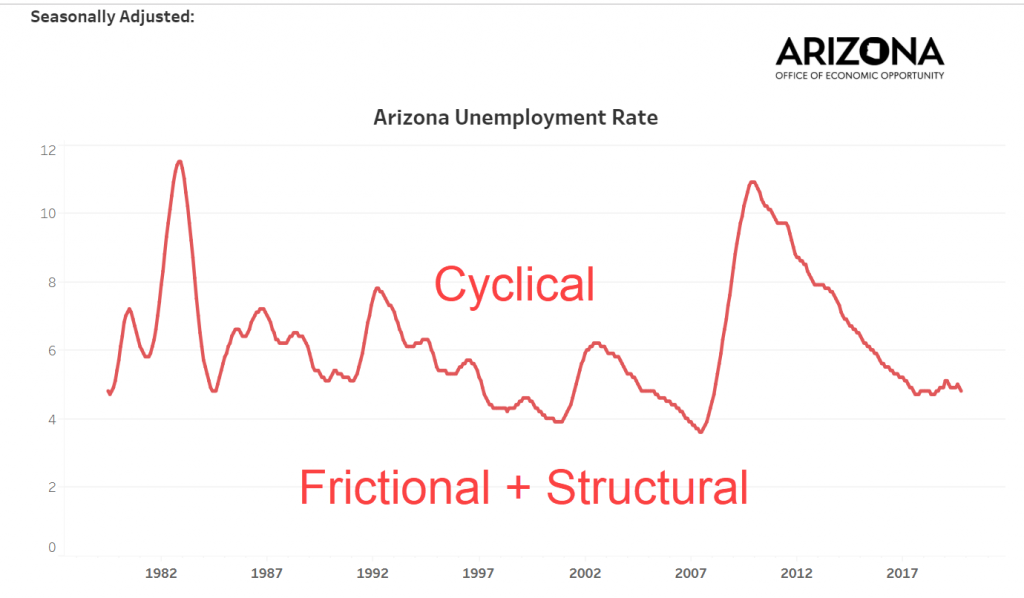

Recessions Create Cyclical Unemployment

Unemployment is composed of three conceptual pieces: frictional, structural and cyclical elements. The first piece, frictional unemployment, is the normal amount of slack you have in any labor market where people occasionally move between jobs and businesses open and close. Unemployment compensation helps these workers, when they lose their job through no fault of their own to have an income through these usually brief transition periods.

Structural unemployment is the result of business changes best described by economist Joseph Schumpeter, who aptly described capitalism as a process of “creative destruction. During the late 1970s, the United States experienced a period of deindustrialization as many manufacturing jobs began to move overseas. As a consequence, a number of workers, such as autoworkers, lost their jobs within industries that were shrinking, creating a mismatch between their well-developed skill set and available employment. This occurs continually in our economy and the result of these transitions is known as structural unemployment. Most recently structural unemployment has been the result of technology changes that have allowed employers to outsource jobs. This has occurred most commonly in the engineering and customer service business sectors. Retraining assistance is often used to help affected workers along with unemployment compensation benefits.

The final type of unemployment is cyclical, referring to changes in macroeconomic business cycles. During boom times cyclical unemployment disappears and we have what is called “full employment”, where unemployment rates equal frictional plus structural unemployment. These theoretical constructs are not always easily quantified in practice, so there is some dispute about exactly when full-employment is achieved. However, when profits slip and the economy slows down, we quickly see evidence of cyclical unemployment. Unlike the other kinds of unemployment, this kind of unemployment is widespread and exists in an environment where finding new work takes extraordinary time. At this point, unemployment compensation offers a critical safety net While state programs unemployment compensation benefits like Arizona’s typically last up to 26 weeks, the federal government often provides supplemental weeks of benefits as it did during the Great Recession. Arizona’s unemployment rate is tracked from 1979-2019 below in Figure 1 (with seasonal adjustments).

FIGURE 1

Arizona’s Inadequate Unemployment Compensation System

There are two fundamental problems with Arizona’s unemployment compensation system:

Problem 1: Restricted Accessibility

Each state, subject to federal oversight, sets its own unemployment compensation, including eligibility and benefit levels. Arizona stands out for having the most aggressive income restrictions on accessing unemployment benefits, combined with some of the lowest benefits in the country.

Unemployment insurance is an insurance program funded through taxes on employers. The system covers workers who are employed—not those who are self-employed.

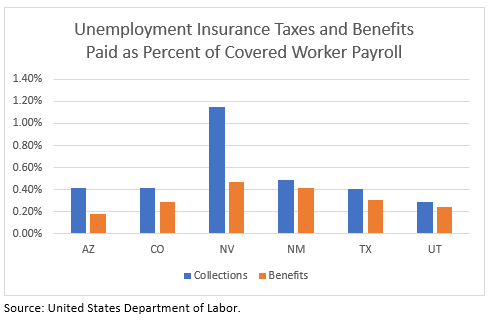

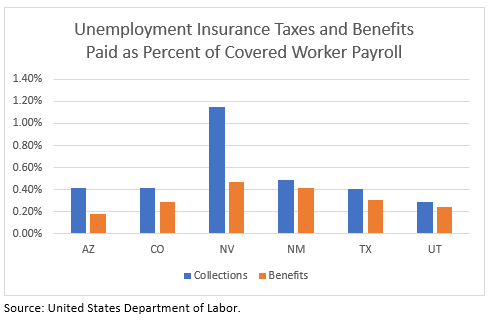

Generally, to qualify for unemployment compensation, a person must have lost her job through no fault of their own, such as being fired “for cause” or quitting. Like other insurance, employers pay taxes based on their experience rating, meaning if the employer tends to layoff people frequently, the employer will have a higher tax rate (or premium) than an employer who rarely lays off workers. Tax rates are also impacted by the state’s unemployment trust fund that pays out benefits. States like Nevada and Arizona, for instance, were hit particularly hard during the last recession. Consequently, a portion of contributions are going to build up the trust fund as opposed to providing benefits. Figure 2 shows that Arizona provides very low benefits (0.16% of covered worker payroll) and that there is a gap between contributions (0.42% of covered worker payroll) and benefits that is helping rebuild the trust fund. A starker pattern can be seen for Nevada.

FIGURE 2

While a person must lose their job through no fault of their own, states also create minimum income barriers to those who apply for unemployment insurance. While most states expect and enforce (including Arizona) that unemployed workers actively make job search contacts each week for full-time work, many people were formerly employed in positions that were less than full-time.

As anyone who works in a restaurant or retail knows, work hours can fluctuate considerably. Presently, Arizona workers employed in a minimum wage job will need to demonstrate a full quarter of the year in which they maintained on average 30 hours per week or 390 weeks total at minimum wage (less hours needed if pay is higher). The state legislature raised it to this standard in 2012 from a flat $1,500. As the minimum wage was $7.65 at the time, this effectively doubled the standard to about $3,000. Now with the passage of Prop. 204 raising the minimum wage to $12 an hour in 2020, the $1,500 standard will have been tripled.

No other state provides a restriction to qualify for benefits which is that high.

Most states provide minimum income amounts. For example, in Nevada, a person can qualify with as little as $400 in their highest quarter and $600 overall for the past year. Note at that minimal level in Nevada, one’s benefits are only $16 a week. The most restrictive state after Arizona in the Southwest is Utah, where annual earnings must be $3,800 (8% of the state’s fiscal year wages). At Utah’s minimal level, benefits are only $92 a week. In Texas and Colorado one can qualify with an annual income of $2,500. By sharp contrast, in Arizona, unless a person earned at least $4,290 in a calendar quarter (going up to $4,680 next year) and at least $6,435 annually (going up to $7,020 next year), they cannot qualify for unemployment benefits at all.

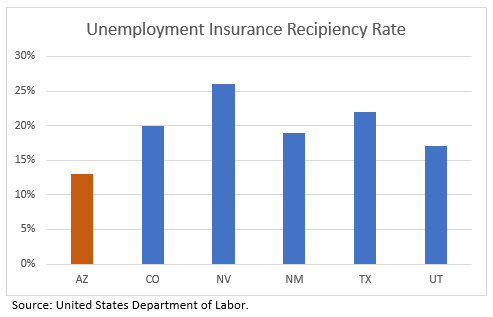

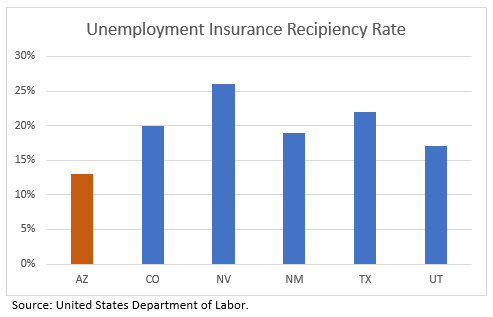

FIGURE 3

Consequently, as shown in Figure 3, Arizona has half the portion of unemployed workers receiving benefits as Nevada, one in eight compared to one in four, respectively. Likewise, about 50 percent more people proportionately receive benefits in the other Southwestern states than in Arizona.

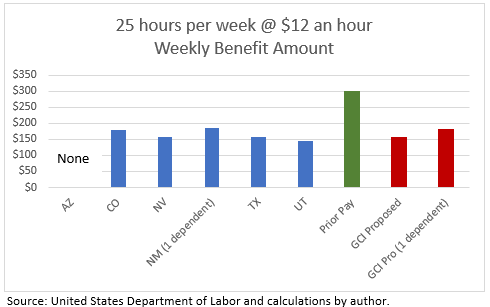

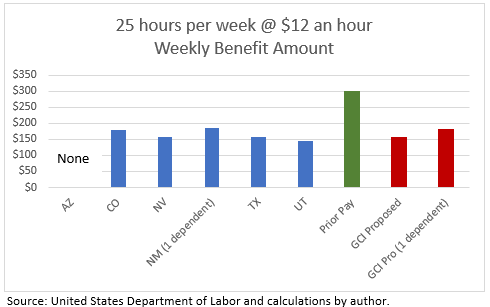

This is most starkly demonstrated in Figure 4 if you take a worker who earns $15,000 annually working an average of 25 hours a week at $12 an hour, Arizona’s minimum wage as of next year. In Arizona that worker does not qualify for unemployment compensation benefits, whereas, in Texas, that same worker would receive weekly benefits of $156. Imagine the different impact on a woman’s family going from $300 a week to nothing in Arizona, compared to $300 a week to $156 in Texas.

FIGURE 4

Recommendation

Change the minimum earning quarter amount to qualify for unemployment insurance to 260 x minimum wage ($3,120 next year) OR alternatively $7,000 over the four-quarter base period (annual amount). This criterion would still be one of the most stringent in the United States and more stringent than other Southwestern states, but it would no longer block people who have had regular employment from accessing unemployment benefits.

In addition, Arizona’s legislature should amend the portion of Chapter 340 (SB1398), of the 53rd Legislative Session (2018). Workers should not be required to take the first job offered after four weeks of benefits or face loss of unemployment compensation even if the job poses issues with travel, hours, pay level or wasn’t even the one applied for. The federal government has already interceded to say the state requirement is not consistent with federal law, so it is currently not in force. The Arizona Department. of Economic Security already had sufficient “suitable work” and job search requirements prior to the state adopting this onerous provision.

Problem 2: Lack of Benefit Adequacy

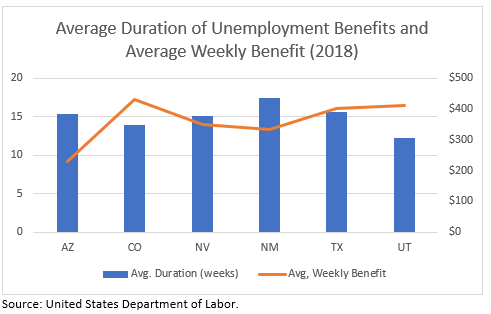

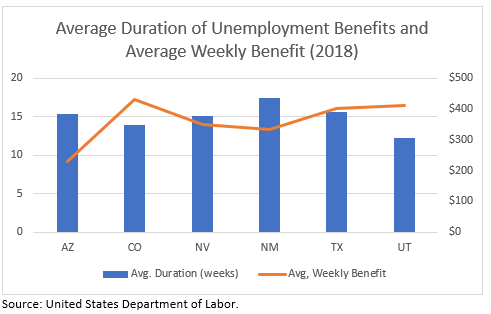

In the past, policymakers have been concerned that unemployment benefits led to prolonged and unnecessarily extended job searches. But as seen in Figure 5, even though average weekly benefits in Texas are $401 compared to only $231 in Arizona, both states in 2018 had identical average weekly durations of unemployment benefits—the same pattern holds true across other states in the Southwest, illustrating a lack of empirical evidence that higher benefits lead to higher stints of unemployment.

FIGURE 5

The state has not adjusted its maximum unemployment compensation in 15 years—such that the $240 cap, raised in 2004, now adjusted for inflation is only worth about $175 in 2004 dollars. In 2004, the newly adopted maximum unemployment compensation cap put Arizona with third lowest benefit cap in the nation.

The median American household has about $12,000 in savings, but that drops dramatically once you look at those households below that amount. Among households between the 20th and 40th percentile in income, median savings is less than $1,000—not enough to survive a significant loss of income without substantial risk to children. The median household in the bottom 20th percentile in income has no savings at all—living paycheck to paycheck. The households that have the least savings are ones that are also most likely to have young children, so an inadequate unemployment compensation places these children and their families at risk for divorce or other family disruptions as well as greater mental and physical health issues.

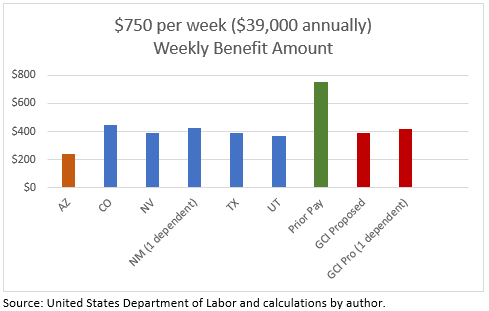

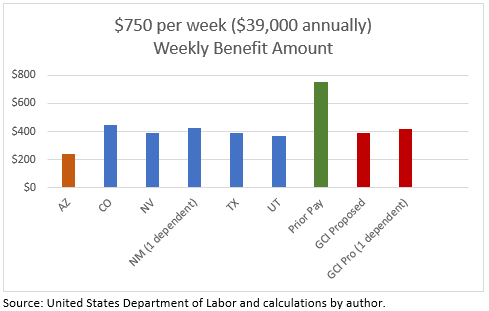

By contrast other states in the Southwest tie their benefit cap to their state’s average weekly wage. Consequently, as shown in Figure 6 in Arizona someone who formerly earned $39,000 annually receives about one-third of her former income as unemployment compensation, whereas in other Southwestern states the amount is just over half.

FIGURE 6

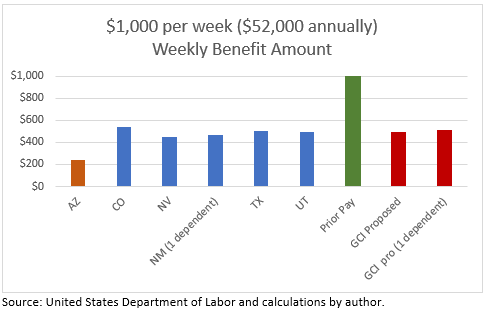

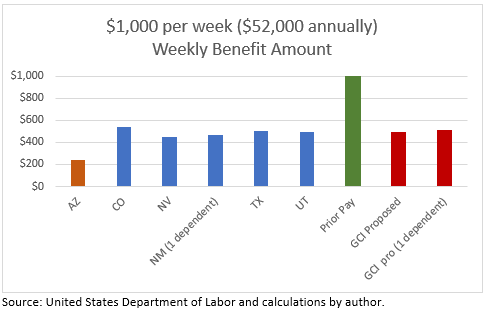

As an unemployed worker’s income rises, the replacement deficit worsens. So, a worker who formerly earned $1,000 a week ($52,000 annually) only has one-fourth of her earnings replaced by unemployment compensation, where as in other Southwestern states it is approximately half (see Figure 7).

FIGURE 7

Recommendation

Replace the current $240 cap on weekly unemployment benefits compensation with a cap of one half of the average weekly wage of the prior calendar year. In 2018, the average weekly wage of covered employees in Arizona was $980, so the benefit cap would be $490. This cap would adjust annually as is done in all other Southwestern states and most other states in the country.

In addition, as modeled by New Mexico, a dependent allowance of $25 per week per dependent with a cap of $50 per week should be added, making the benefit cap for an unemployed worker with one dependent $515 and with two or more dependents $540.[1] This would ensure some added financial support for children during times of economic distress.

Dave Wells holds a doctorate in Political Economy and Public Policy and is the Research Director for the Grand Canyon Institute, a centrist fiscal policy think tank founded in 2011. He can be reached at DWells@azgci.org or contact the Grand Canyon Institute at (602) 595-1025.

The Grand Canyon Institute, a 501(c) 3 nonprofit organization, is a centrist think tank led by a bipartisan group of former state lawmakers, economists, community leaders and academicians. The Grand Canyon Institute serves as an independent voice reflecting a pragmatic approach to addressing economic, fiscal, budgetary and taxation issues confronting Arizona.

Grand Canyon Institute

P.O. Box 1008

Phoenix, Arizona 85001-1008

GrandCanyonInsitute.org

[1] Note actual formula is that the dependent allowance cannot exceed half of the weekly benefit level. Weekly benefits are based on the highest quarter. With the 390 hours at minimum wage or GCI’s proposed 260 hours at minimum wage, the full dependent allowance would apply. However, with the $7,000 annual alternative if the highest quarter had $2,000 in earnings the weekly benefit amount would be $80, so the maximum dependent allowance would be $40 if the unemployed person had two dependents.

Labor Force

Labor Force