Budget

Budget

State-Only Medicaid for Childless Adults: Costing More and Getting Less

May 13, 2013Many of our conservative lawmakers are no fans of government health care and have suggested that instead of expanding Medicaid in line with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) that Arizona continue its enrollment freeze on childless (non-custodial) adults while having the state take over financing the program, suggesting the rainy day fund with $450 million as a possible revenue source.

In this analysis The Grand Canyon Institute (GCI) explores the fiscal ramifications of that policy option and compares it to two Medicaid expansion scenarios. One scenario where the federal government provides the matching funds as stated in the ACA, including an enhanced match for childless adults, moving from 85 percent in FY2015 to 90 percent in FY2017 and initial full coverage for those adults newly eligible for Medicaid up to 133 percent of the federal poverty line with a 5 percent state portion in FY2017 (see Table 2 in Appendix).

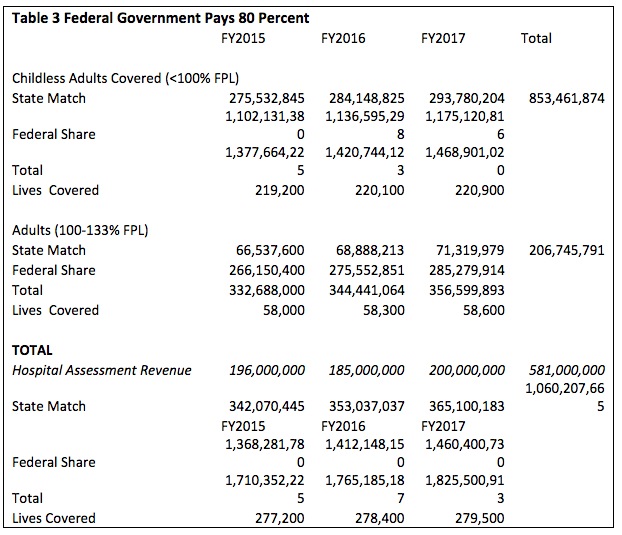

Throughout the Medicaid expansion debate, some conservative lawmakers have continually expressed concern that the federal government will not live up to its obligation due to financial constraints at the federal level. So in the second scenario, GCI looks at a situation where the federal government pays the lowest amount in Governor Jan Brewer’s proposal, 80 percent, doubling the net cost to the state. Each of the scenarios were examined over the first three full years of Medicaid expansion from fiscal years 2015 to 2017 (see Table 3 in Appendix).

State-Only Medicaid for Childless Adults:

Costing More and Getting Less

By Dave Wells, Ph.D., Research Director

Grand Canyon Institute

Many of our conservative lawmakers are no fans of government health care and have suggested that instead of expanding Medicaid in line with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) that Arizona continue its enrollment freeze on childless (non-custodial) adults while having the state take over financing the program, suggesting the rainy day fund with $450 million as a possible revenue source.

In this analysis The Grand Canyon Institute (GCI) explores the fiscal ramifications of that policy option and compares it to two Medicaid expansion scenarios. One scenario where the federal government provides the matching funds as stated in the ACA, including an enhanced match for childless adults, moving from 85 percent in FY2015 to 90 percent in FY2017 and initial full coverage for those adults newly eligible for Medicaid up to 133 percent of the federal poverty line with a 5 percent state portion in FY2017 (see Table 2 in Appendix).

Throughout the Medicaid expansion debate, some conservative lawmakers have continually expressed concern that the federal government will not live up to its obligation due to financial constraints at the federal level. So in the second scenario, GCI looks at a situation where the federal government pays the lowest amount in Governor Jan Brewer’s proposal, 80 percent, doubling the net cost to the state. Each of the scenarios were examined over the first three full years of Medicaid expansion from fiscal years 2015 to 2017 (see Table 3 in Appendix).

Fiscal year 2014 will be a ramping up year for Medicaid expansion that starts in the middle of the fiscal year. A state-only funded program would cost considerably more in that year, about $140 million extra, since all federal funding for childless adults would stop on January 1 and the state would need to fully pay for care for an estimated 56,000 people, a cost estimated by the Joint Legislative Budget Office at $195 million. By contrast, expansion enrollment in Medicaid will roll out gradually and GCI projects by the end of the fiscal year half of full enrollment will be reached, such that the expense to the state should be about $54 million (JLBC says $58 million), which would be covered by a hospital assessment. As such, fiscal year 2014 was excluded from the analysis to create a fairer comparison.

Under the first scenario, the GCI finds expanding Medicaid will cost half a billion dollars over the first three full years, which Governor Jan Brewer has proposed be funded through an assessment on hospitals.

Under the second scenario, GCI finds expanding Medicaid will cost $1 billion over the three years, twice as much, and the difference, about $500 million could potentially have to come from the General Fund. Both of these figures should be interpreted as high-end estimates, as Arizona in the past has taken just over three years to reach full enrollment in health care expansions with Prop. 204 “Healthy Arizona” and KidsCare. The GCI analysis, following the JLBC and the Executive’s lead, assumes full enrollment is reached within six months, which helps assure more careful budget planning, but overstates probable state financial responsibilities in FY2015 and FY2016 by $65 million if the federal government pays their full share and by around $130 million, if the federal government pays 80 percent.

So how much would it cost to maintain the freeze on childless adults and switch that part of AHCCCS to an entirely state-run operation over three years? A state-run program would cost $875 million over three years, about $350 million more than if the federals government fully pays its share of Medicaid expansion, and about $150 million less than if the federal government only pays 80 percent. As these individuals are already enrolled, and a gradual decline in enrollment is built into the estimate. Unlike the Medicaid expansion estimate, it’s far less likely this is an overestimate of costs.

But there’s a big catch with the $875 million estimate, uncompensated healthcare costs. Uncompensated healthcare costs are costs that are absorbed by providers, whether public or private, due to the inability of the person receiving care to pay, and this is beyond public and private financing to cover these individuals.

Focusing on the ACA optional coverage populations, childless adults under the poverty line and all adults between 100 and 133 percent of the poverty line, expanding Medicaid will mean about 200,000 more Arizonans will have health care coverage than if the state only provides insurance to about 40,000 childless adults in its state-run program. Since new enrollees are locked out, the state-only program’s size gradually declines over time. Those 200,000 uninsured adults will still have medical needs that will not be paid for and will result in added uncompensated costs compared to Medicaid expansion.

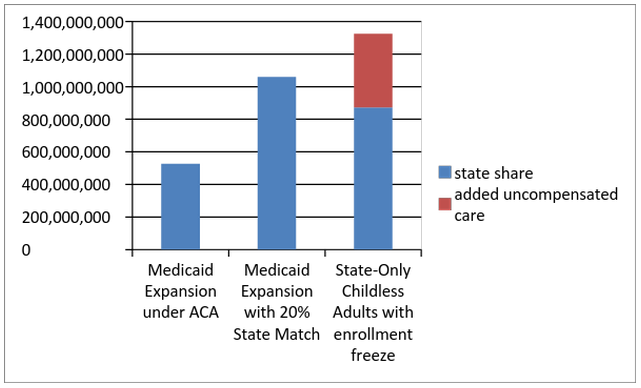

Chart 1

Cost to Arizona (public and private sector)

FY2015 to FY2017

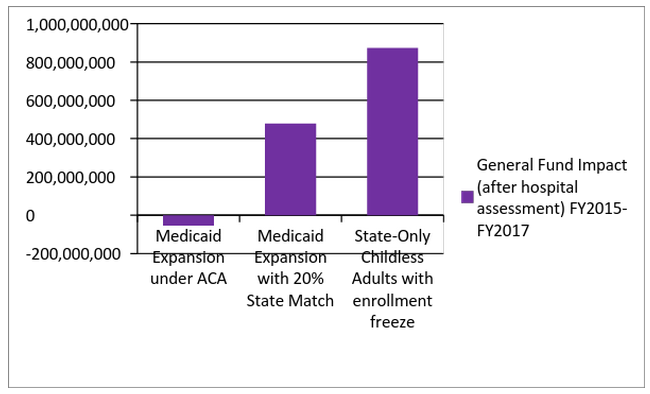

Chart 2

General Fund Impact

(after hospital assessment)

FY2015 to FY2017

GCI estimates those costs are $450 million over the three years, far larger than the $150 million in “savings” that the state theoretically accrues by not expanding Medicaid, if the federal government only pays 80 percent. Those “savings” also disregard that Medicaid expansion will be entirely or largely paid for by an assessment on hospitals, whereas a state-only program would have no such hospital assessment to rely upon.

These impacts are shown in Charts 1 and 2.

Chart 1 illustrates the total financial costs on the public and private sector from each scenario. The cost is greatest if the state does not expand Medicaid, even if the federal government requires a 20 percent state match, due to the rise in uncompensated healthcare costs.

Chart 2 focuses on the state General Fund impacts. Hospital assessment estimated revenue is provided by the JLBC with FY2017 projected by GCI. The charts shows that if the Federal government fulfills its obligations, then the hospital assessment actually brings in more revenue than state General Fund costs.

f the state match is 20 percent, the hospital assessment reduces the impact on the General Fund by over half compared to Chart 1. The hospital assessment does not apply if the state fails to expand Medicaid, so the most costly option for the General Fund is a state-only childless adult program with an enrollment freeze.

Furthermore, as the rainy day fund has $450 million in it and if the $195 million cost in fiscal year 2014 is included, the total cost of the state-only funding proposal costs $1.07 billion from fiscal year 2014 through fiscal year 2017, draining the rainy day fund completely, pulling from the General Fund, as well as leaving the state in a precarious position when the next economic downturn hits, when Medicaid rolls will rise, regardless of what course of action the state chooses.

Some lawmakers have suggested the decision on expanding Medicaid can wait, when, in fact, waiting will be a costly choice for the state. Abandoning coverage of childless adults completely on January 1, 2014 will create a huge public backlash in an election year and leave the state open to a lawsuit for failing to cover Prop. 204’s (“Healthy Arizona”) voter mandates, despite its loose “available funds” language. Choosing a state-only run program could also lead to litigation, especially, if the deal with the Federal government under the ACA proves more fiscally sound as Medicaid expansion leads to better health outcomes and is more consistent with Prop. 204.

This analysis suggests with a hospital assessment in place that would cover all or most of the cost of expanding Medicaid that even if the federal government’s match declines to 80 percent, the state will be in a stronger position fiscally than if the state were to continue its freeze on enrollment for childless adults as a state-only funded program.

Details on estimates are provided in the appendix.

APPENDIX

In September 2012, GCI issued its first economic analysis of Medicaid expansion under the ACA using figures from a publicly available AHCCCS spreadsheet from August 2012 to estimate costs and economic benefits for three options for the state: maintaining current policy, funding to 100 percent of the poverty line (Prop. 204), and fully funding Medicaid expansion. Since that time, while the enrollment figures in that spreadsheet have been fairly consistent with the estimates used by the Executive and Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC), the per enrollee costs for some populations were significantly higher in the AHCCCS spreadsheet than what’s been subsequently used by JLBC and the Executive. GCI’s own independent analysis of costs using a recent actuarial study on the ACA’s impact also confirms that those costs were likely too high.

In this analysis, our goal is to align our estimates on a per enrollee basis with the costs being used by the JLBC, which provides fiscal advice to lawmakers. In addition, we use JLBC estimates for the declining childless adult covered population under an enrollment freeze, and extend their methodology by one year to 2017. We use the same annual inflation adjustment of three percent as JLBC throughout the analysis, and like JLBC we assume an annual case load growth of 0.5 percent per annum.

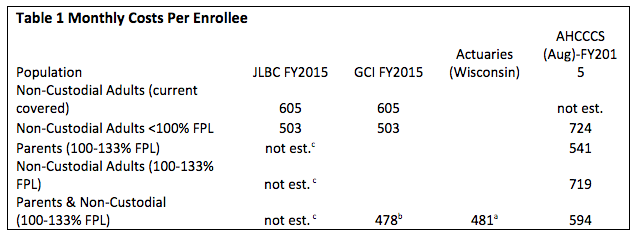

Costs are typically shown as average per enrollee per month, which GCI calculates by taking the average annual cost divided by the average annual enrollees and then dividing that by 12. Those figures are shown below, along with those provided by the Society of Actuaries study.

Non-Custodial adults, i.e., childless adults, typically are older and have greater health issues than do parents. Consequently, non-custodial adults are more costly. Readers will note that for the current covered non-custodial adults, the monthly cost is $100 higher. Those long-term on Medicaid are more likely to be disabled and have chronic health conditions. They are less likely to have income fluctuations or other circumstances that would lead to them losing Medicaid coverage, and with the enrollment freeze not being able to re-qualify.

Note that in Tables 2 and 3, the childless adult category under the poverty line is a blending of those costing $605 a month and those costing $503 a month.

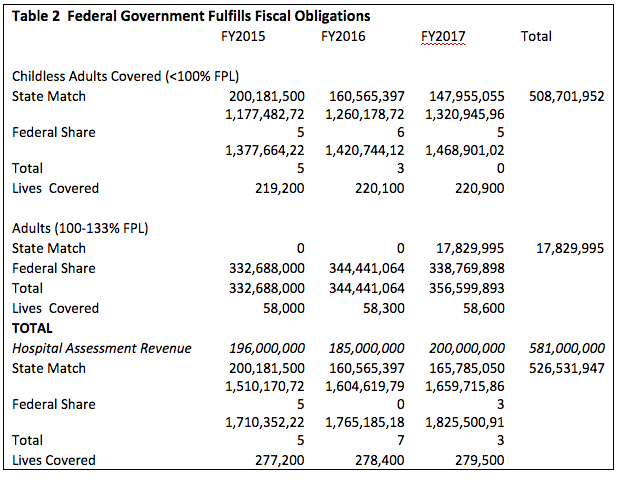

Tables 2 through 4 illustrate the three scenarios. In Table 2, Arizona expands Medicaid and the federal government lives up to its fiscal obligations, which includes an enhanced match of 85 to 90 percent for childless adults and fully paying for those above the poverty line and in FY2017 beginning the gradual ramp down to where the Federal government pays 90 percent in FY2020. The cost to the state is $526 million with 279,500 people having health insurance. This number includes those non-custodial adults who currently have coverage under the enrollment freeze as well as added eligibility for those below 133 percent of the FPL.

In Table 3, the state’s cost doubles to $1.06 billion because in this scenario the federal government only pays 80 percent of costs. However, the number covered remains the same. The difference between these two scenario would need to be partially funded from the General Fund, about $165 million a year.

The hospital assessment that would help pay for these costs is estimated using the JLBC and extending their series by a year as follows:

FY2015 $196 million (JLBC)

FY 2016 180 million (JLBC)

FY 2017 $200 million (author)

TOTAL: $576 million

As illustrated in chart 2, the $576 million more than covers the costs shown in Table 2 and covers most of the cost in Table 3. However, the assessment would not apply to Table 4.

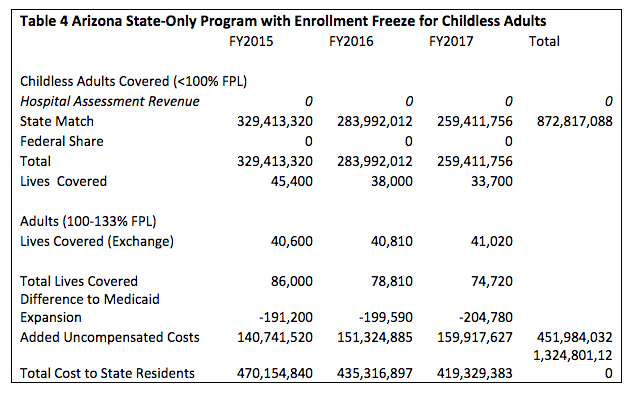

Table 4 shows the fiscal impact if the state were to go it alone, and maintain its freeze on coverage for childless adult enrollment. Following the JLBC, we presume enrollment will decline by about 1 percent per month, and have extended their estimates to FY2017. In addition, if Arizona does not expand Medicaid eligibility, uninsured adults with incomes between 100 and 133 percent of the federal poverty line will qualify for subsidized private insurance through the federally-operated exchange. GCI includes the estimated enrollment in exchanges, which is expected based on analyses of programs in other states to be 70 percent of the number that would enroll in Medicaid since the premium would be two percent of their income, which acts as a disincentive to enroll.

In Table 4 the total cost to the state is $873 million of the three years, higher than Table 2, but lower than Table 3. However, Table 4 provides no hospital assessment and includes an additional cost since 200,000 less people have health insurance coverage. Consequently, uncompensated health care costs rise by approximately $150 million a year, totaling $451 million across the three years.

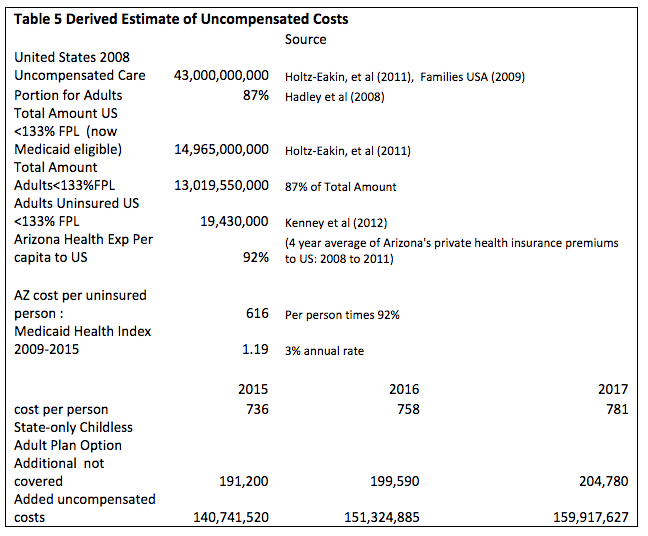

Table 5 derives uncompensated costs. It begins with an estimate of uncompensated healthcare costs. Uncompensated costs are those costs not paid for at all, so it’s after any charity programs funded publicly or privately to pay for costs. A 2008 estimate using the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data provided by conservative economists in an amicus brief opposed to the Affordable Care Act’s insurance mandate included a breakdown of uncompensated costs.

Note that in Tables 2 and 3, the childless adult category under the poverty line is a blending of those costing $605 a month and those costing $503 a month.

Tables 2 through 4 illustrate the three scenarios. In Table 2, Arizona expands Medicaid and the federal government lives up to its fiscal obligations, which includes an enhanced match of 85 to 90 percent for childless adults and fully paying for those above the poverty line and in FY2017 beginning the gradual ramp down to where the Federal government pays 90 percent in FY2020. The cost to the state is $526 million with 279,500 people having health insurance. This number includes those non-custodial adults who currently have coverage under the enrollment freeze as well as added eligibility for those below 133 percent of the FPL.

In Table 3, the state’s cost doubles to $1.06 billion because in this scenario the federal government only pays 80 percent of costs. However, the number covered remains the same. The difference between these two scenario would need to be partially funded from the General Fund, about $165 million a year.

The hospital assessment that would help pay for these costs is estimated using the JLBC and extending their series by a year as follows:

FY2015 $196 million (JLBC)

FY 2016 180 million (JLBC)

FY 2017 $200 million (author)

TOTAL: $576 million

As illustrated in chart 2, the $576 million more than covers the costs shown in Table 2 and covers most of the cost in Table 3. However, the assessment would not apply to Table 4.

Table 4 shows the fiscal impact if the state were to go it alone, and maintain its freeze on coverage for childless adult enrollment. Following the JLBC, we presume enrollment will decline by about 1 percent per month, and have extended their estimates to FY2017. In addition, if Arizona does not expand Medicaid eligibility, uninsured adults with incomes between 100 and 133 percent of the federal poverty line will qualify for subsidized private insurance through the federally-operated exchange. GCI includes the estimated enrollment in exchanges, which is expected based on analyses of programs in other states to be 70 percent of the number that would enroll in Medicaid since the premium would be two percent of their income, which acts as a disincentive to enroll.

In Table 4 the total cost to the state is $873 million of the three years, higher than Table 2, but lower than Table 3. However, Table 4 provides no hospital assessment and includes an additional cost since 200,000 less people have health insurance coverage. Consequently, uncompensated health care costs rise by approximately $150 million a year, totaling $451 million across the three years.

Table 5 derives uncompensated costs. It begins with an estimate of uncompensated healthcare costs. Uncompensated costs are those costs not paid for at all, so it’s after any charity programs funded publicly or privately to pay for costs. A 2008 estimate using the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data provided by conservative economists in an amicus brief opposed to the Affordable Care Act’s insurance mandate included a breakdown of uncompensated costs.

The household component of MEPS is used in these analyses. The United States Department of Health Services describes the methodology.

The Household Component (HC) collects data from a sample of families and individuals in selected communities across the United States, drawn from a nationally representative subsample of households that participated in the prior year’s National Health Interview Survey (conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics).

During the household interviews, MEPS collects detailed information for each person in the household on the following: demographic characteristics, health conditions, health status, use of medical services, charges and source of payments, access to care, satisfaction with care, health insurance coverage, income, and employment.

The panel design of the survey, which features several rounds of interviewing covering two full calendar years, makes it possible to determine how changes in respondents’ health status, income, employment, eligibility for public and private insurance coverage, use of services, and payment for care are related.

The economists’ uncompensated cost estimate is identical to the one put forward by Milliman, Inc., an independent actuarial consulting firm, for Families USA. Of $43 billion in uncompensated health care costs in 2008, the economists identify 34.8 percent of the total as coming from uninsured individuals who would be eligible for Medicaid due to incomes less than 133 percent of the FPL. They also control for immigration status with a separate category for uncompensated care due to immigration status. An earlier study of uncompensated care using the same data source but from 2002 found that 87% of uncompensated costs are attributable to adults, which is likely due to their greater health care expenses compared to children and that they are less likely to be covered by government-run programs.

To obtain an estimate of the uninsured that would be eligible for Medicaid under the ACA a recent Urban Institute paper provides an estimate of both those adults 19-64 who are currently eligible but not enrolled as well as those adults 19-64 uninsured that will be newly eligible for Medicaid under the ACA. The Urban Institute estimates 19.4 million Medicaid eligible adults. All population data derived comes from the Bureau of the Census’ American Community Survey (ACS).

In addition, health care costs in Arizona are lower than the national average, part of that has to do with reduced incomes and higher numbers of people without insurance, so to better control for those differences, GCI looked at four years of average private insurance premiums for Arizona compared to the United States, 2008 to 2011, and found Arizona’s to be 92 percent of the national average. The net result is an uncompensated cost per uninsured ACA Medicaid eligible adult in 2008 of $616 for Arizona. That number is adjusted by a Medical inflation index at three percent per year to generate the estimates that appear at the end of Tables 4 and 5.

Dave Wells holds a doctorate in Political Economy and Public Policy and is the Research Director for the Grand Canyon Institute.

Reach the author at DWells@azgci.org or contact the Grand Canyon Institute at (602) 595-1025.

The Grand Canyon Institute, a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, is a centrist think-thank led by a bipartisan group of former state lawmakers, economists, community leaders, and academicians. The Grand Canyon Institute serves as an independent voice reflecting a pragmatic approach to addressing economic, fiscal, budgetary and taxation issues confronting Arizona.

Grand Canyon Institute

P.O. Box 1008

Phoenix, AZ 85001-1008

GrandCanyonInstitute.org